Genetic history of Europe

[2] Divergence into genetically distinct sub-populations within Western Eurasia is a result of increased selection pressure and founder effects during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, Gravettian).

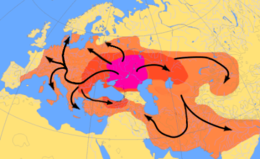

These Bronze Age population replacements are associated with the Bell Beaker and Corded Ware cultures archaeologically and with the Indo-European expansion linguistically.

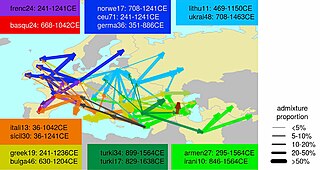

[8][9][10] Admixture rates varied geographically; in the late Neolithic, WHG ancestry in farmers in Hungary was at around 10%, in Germany around 25% and in Iberia as high as 50%.

They were eventually replaced by anatomically modern humans (AMH; sometimes known as Cro-Magnons), who began to appear in Europe circa 40,000 years ago.

[21][22] By 2010, findings by Svante Pääbo (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology at Leipzig, Germany), Richard E. Green (University of California, Santa Cruz), and David Reich (Harvard Medical School), comparing the genetic material from the bones of three Neanderthals with that from five modern humans, did show a relationship between Neanderthals and modern people outside Africa.

Currently the oldest sample of Haplogroup I (M170), which is now relatively common and widespread within Europe, has been found to be Krems WA3 from Lower Austria dating back to about 30–31,000 ybp.

[25] Earlier research into Y-DNA had instead focused on haplogroup R1 (M173): the most populous lineage among living European males; R1 was also believed to have emerged ~ 40,000 BP in Central Asia.

[27] Thus the genetic data suggests that, at least from the perspective of patrilineal ancestry, separate groups of modern humans took two routes into Europe: from the Middle East via the Balkans and another from Central Asia via the Eurasian Steppe, to the north of the Black Sea.

Martin Richards et al. found that 15–40% of extant mtDNA lineages trace back to the Palaeolithic migrations (depending on whether one allows for multiple founder events).

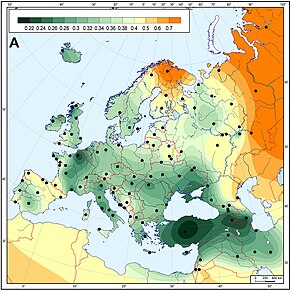

According to the classical model, people took refuge in climatic sanctuaries (or refugia) as follows: This event decreased the overall genetic diversity in Europe, a "result of drift, consistent with an inferred population bottleneck during the Last Glacial Maximum".

[26] As the glaciers receded from about 16,000–13,000 years ago, Europe began to be slowly repopulated by people from refugia, leaving genetic signatures.

[32] Today, R1b dominates the y chromosome landscape of western Europe, including the British Isles, suggesting that there could have been large population composition changes based on migrations after the LGM.

[13] This genetic shift shows that Near East populations had probably already begun moving into Europe during the end of the Upper Paleolithic, about 6,000 years earlier than previously thought, before the introduction of farming.

This has often been linked to the spread of farming technology during the Neolithic, which has been argued to be one of the most important periods in determining modern European genetic diversity.

[25]: Here, the clade E-M35 is referred to as "Eu 4" Rosser et al. rather saw it as a (direct) 'North African component' in European genealogy, although they did not propose a timing and mechanism to account for it.

[46] Concerning timing the distribution and diversity of V13 however, Battaglia[47] proposed an earlier movement whereby the E-M78* lineage ancestral to all modern E-V13 men moved rapidly out of a Southern Egyptian homeland and arrived in Europe with only Mesolithic technologies.

In contrast to Battaglia, Cruciani[48] tentatively suggested (i) a different point where the V13 mutation happened on its way from Egypt to the Balkans via the Middle East, and (ii) a later dispersal time.

Another theory about the origin of the Indo-European language centres around a hypothetical Proto-Indo-European people, who, according to the Kurgan hypothesis, can be traced to north of the Black and Caspian Seas at about 4500 BCE.

The geographical spread of haplogroup N in Europe is well aligned with the Pit–Comb Ware culture, whose emergence is commonly dated c. 4200 BCE, and with the distribution of Uralic languages.

Mitochondrial DNA studies of Sami people, haplogroup U5 are consistent with multiple migrations to Scandinavia from Volga-Ural region, starting 6,000 to 7,000 years before present.

[58][59] According to Iosif Lazaridis, "the Ancient North Eurasian ancestry is proportionally the smallest component everywhere in Europe, never more than 20 percent, but we find it in nearly every European group we’ve studied.

[58] On November 16, 2015, in a study published in the journal Nature Communications,[58] geneticists announced that they had found a new fourth ancestral "tribe" or "strand" which had contributed to the modern European gene pool.

Apart from the outlying Saami, all Europeans are characterised by the predominance of haplogroups H, U and T. The lack of observable geographic structuring of mtDNA may be due to socio-cultural factors, namely the phenomena of polygyny and patrilocality.

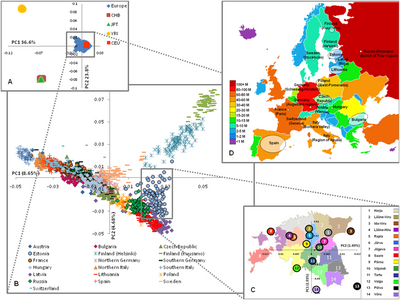

Fst (Fixation index) was found to correlate considerably with geographic distances ranging from ≤0.0010 for neighbouring populations to 0.0200–0.0230 for Southern Italy and Finland.

[92][93] Within Russia, Komi people, who live in the northeastern regions and are part of the Uralic language family that also includes Finns, form a pole of genetic diversity that is distinct from other populations, and characterized by a higher European hunter-gatherer (WHG) and Ancient North Eurasian ancestry.

This Siberian component is itself a composition of Ancient North Eurasian and East Asian-related ancestry from Eastern Siberia, maximized among Evenks and Evens or Nganasans.

These maps show peaks and troughs, which represent populations whose gene frequencies take extreme values compared to others in the studied area.

These properties include the direct, unaltered inheritance of mtDNA and NRY DNA from mother to offspring and father to son, respectively, without the 'scrambling' effects of genetic recombination.

This would result in an overestimation of haplogroup age, thus falsely extending the demographic history of Europe into the Late Paleolithic rather than the Neolithic era.

No matter how accurate the methodology, conclusions derived from such studies are compiled on the basis of how the author envisages their data fits with established archaeological or linguistic theories.