Kingdom of Singapura

As a result, the kingdom's fortified capital was attacked by at least two major foreign invasions before it was finally sacked by Majapahit in 1398 according to the Malay Annals, or by the Siamese according to Portuguese sources.

[9] According to the Malay Annals, Sang Nila Utama and his men were exploring Tanjong Bemban while in Bintan when he spotted an island with white sandy beach from a high point.

For example, it has been proposed that the name Singapura was adopted by Parameswara as an indication that he was re-establishing in Temasek the lion throne that he had originally set up in Palembang as a challenge to the Javanese Majapahit Empire.

Historians are therefore generally in doubt over the historicity of the kingdom as described in the semi-historical Malay Annals,[3][13] nevertheless some consider Singapura to be a significant polity that existed between the decline of Srivijaya and the rise of Malacca.

[14][15] Some also argued that the author of the Malay Annals, whose purpose is to legitimise the claim of descent from the Palembang ruling house, invented the five kings of Singapura to gloss over an inglorious period of its history.

In contrast, the Malay Annals identifies the fleeing prince and the last king as two different people separated by five generations, Sang Nila Utama and Iskandar Shah respectively.

[20] The only first-hand account of 14th-century Singapore may be the descriptions of a place named Danmaxi (generally identified with Temasek) written by Wang Dayuan in the Daoyi Zhilüe, a record of his travels.

[citation needed] Although the existence of the kingdom as described in the Malay Annals is debatable, archaeological excavations on Fort Canning and its vicinity along the banks of the Singapore River since 1984 by John Miksic have confirmed the presence of a thriving settlement and a trade port there during the 14th century.

[4] The primary source concerning the history of the rulers of Singapura are the Malay Annals, and the rest of this section is mainly built upon reconstructions from its text, although corroborating evidence is scarce and its polemic nature suggests against literal interpretations of this chronicle.

[29][30] According to the Malay Annals, a fleeing Palembang prince named Sang Nila Utama, who claimed to be a descendant of Alexander the Great (via his Islamic interpretation as Iskandar Zulkarnain), took refuge on Bintan Island for several years before he set sail and landed on Temasek in 1299.

[32] These Orang Laut eventually declared him Raja ("king"), and Sang Nila Utama renamed Temasek as "Singapura" and founded his capital around the mouth of the Singapore River.

[35] Within a few decades, the small settlement grew into a thriving cosmopolitan city serving as a port of call for richly laden trade ships traveling through the Malacca Straits region.

He describes Temasek as comprising two settlements – "Ban Zu" (after the Malay word "pancur" or fresh-water spring), a peaceful trading port city under the rule of the king.

He also mentions some of the trade goods bartered in Singapura: red gold, cotton prints, blue satin, lakawood and fine hornbill casques.

According to Wang's account, possibly a few years before he visited Temasek in the 1330s, a Siamese fleet consisting of 70 junks descended upon the island kingdom and launched an attack.

[47] In 1387, Paduka Sri Maharaja was succeeded by Iskandar Shah, commonly identified as the king Parameswara mentioned in the Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires.

[18] As mentioned in the Malay Annals, the story of the fall of Singapura and the flight of its last king begins with Iskandar Shah's accusing one of his concubines of adultery.

Raffles suggested the date of 1160 for Singapura's founding, which was actually taken from Francois Valentijn, who determined in 1724 that this was when Sri Tri Buana (a title associated with Sang Nila Utama) was crowned in Palembang.

Valentijn had used a list of kings available to him that disclosed the stated reign durations of a line of Malay rulers of Singapura, Melaka, and Johor, that ended with Sultan Abdul Jalil Shah IV (r.1699–1720).

[57] Linehan's theory was long discredited by Wang Gungwu's verification that Parameswara and Iskandar Shah were not the same persons, but father and son, as the Ming dynasty records stated.

Next to the Raja were the Orang Besar Berempat (four senior nobles) headed by a Bendahara (equivalent to a Grand Vizier) as the highest-ranking officer and the advisor to the King.

He was then assisted by three other senior nobles based on the order of precedence namely; Perdana Menteri (prime minister), Penghulu Bendahari (chief of treasurer) and Hulubalang Besar (grand commander).

[59] Singapura's rise as a trade-post was concurrent with the era known as Pax Mongolica, where the Mongol Empire's influence over both the overland and maritime silk roads allowed a new global trading system to develop.

Previously, shipping occurred on long-distance routes from the Far East to India or even further west to the Arabian Peninsula, which was relatively costly, risky and time-consuming.

[62] "... have the honour of mixing with those of ashes of Malayan kings ..." According to the Malay Annals, after sacking Singapura, the Majapahit army abandoned the city and returned to Java.

Within decades, the new city grew rapidly to become the capital of Malacca Sultanate and emerged as the primary base in continuing the historic struggles of Singapura against their Java-based rivals.

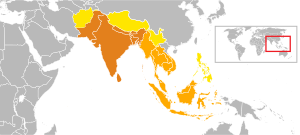

[64] As a major entrepot, Malacca attracted Muslim traders from various part of the world and became a centre of Islam, spreading the religion throughout Maritime Southeast Asia.

The period spanning from Malaccan era right until the age of European colonisation, saw the domination of Malay-Muslim sultanates in trade and politics that eventually contributed to the Malayisation of the region.

[66] The Johor Sultanate emerged as the dominant power around the Straits of Singapore until it was assimilated into the sphere of influence of the Dutch East India Company; the island of Singapore would not regain autonomy from Johor until Sir Stamford Raffles claimed it and its port for the British East India Company in 1819, deliberately invoking its history as related in the Malay Annals,[67] whose translation by Dr. John Leyden he posthumously published in 1821.

[68] The dispute concerning Singapore's legal status, along with other matters arising from British seizure of Dutch colonial possessions during the Napoleonic Wars, was settled by the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, permanently dividing archipelagic and mainland Southeast Asia.