Rajput painting

But despite absorption of the new techniques and subjects from Mughals (and also, to a lesser extent, from European and Deccan painting), Rajput artists never lost their own distinct identity, which manifested itself especially in Indian predilection to universal rather than individual.

Books became an emblem of wealth and power, which meant that Muslim patrons demanded opulence of materials, fine craftsmanship, and continual stylistic and narrative novelty, for painting was also a form of personal entertainment.

"[18] The great centre of Islamic art in Central India at the end of the 15th century was Malwa Sultanate under the rule of Ghiyath Shah (r. 1469–1500), who commissioned Nimatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi, the most important royal manuscript made in his capital, Mandu.

In Seated Man by Basawan (see illustration) we can see how he use European figural modelling and consequent sense of spatial depth to explore physiognomy, character, texture of clothing and the way person positioned herself in space.

In paintings like Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings by Bichitr (Freer, F1942.15a) more important than description of rational, natural world becomes symbolic imagery and imperial decorum.

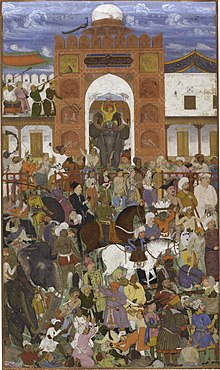

When for Abu'l-Hasan scene from imperial court was an occasion to delight in the variety and quirks of individual appearances, Bichitr in his The accession of Shah Jahan (see illustration) simply demonstrate the power of state ritual.

[36] In accordance with Indian tradition, it had begun "to emphasize the universal aspects of the emperors, rather than their unique qualities, and to diminish the importance of the individualistic, innovative styles practiced by specific painters.

[51] Three artists of the Chunar Ragamala introduce themselves as trained in the imperial workshops by Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd al-Samad and whole set is painted in "a rough, but vigorous and inventive adaptation of Mughal style".

Other styles (e.g. Mewar and Malwa) "are the inheritors of the pre-Mughal Caurapañcāśikā group idiom and carry its essentially conservative values of flatness, abstraction, bold line and bright colour into the 17th century and beyond.

Important manuscripts include Sūryava ṁśaprakāśa (‘Genealogy of the Solar dynasty’, i.e. the Sisodia Rajputs) of 1645, Bhagavata Purana of 1648 and the largest project, monumental Ramayana (see illustration of Ravana, overwhelmed by grief on hearing of his son's death, sends out more forces against Rama), with known volumes dated between 1649 and 1653.

In one of the earliest known examples of the style, Rasikipriya manuscript dated 1634, "backgrounds are plain blocks of colour; a patch of sky hangs at the top of the work, with a broad white band indicating the horizon line.

The textiles show none of the Mughal concern for the physical texture of fabric; while a sense of bodily weight is created by emphasizing and thicknenig the contour lines of the body, "following ancient Indian principles seen most notably in the Buddhist frescoes at Ajanta and continued in later manuscripts on palm leaf.

[67] Personality of Raja Sidh Sen (r. 1684–1727), who was a man of enormous stature and a great warrior as well as a devotee of the Shiva, heavily influence later development of the Mandi school, which acquired a highly distinctive character, especially in its portraits.

[69][70] According to Goswamy and Fischer, who attributed them to painter Kripal of Nurpur (fl c. 1660–1690), those illustrations are "two of the most brilliant series of paintings in the entire art of India"[71] The composition is an assamblege of compartments, each backed by a flat plane of colour.

Their new approach to space allowed newer subjects such as group portraiture, durbar scenes, recording of court ceremonial and grand hunts to enter the traditional repertoire of the Rajput studios.

This anonymous artist got his name from his technique of a "grisaille", a progressively linear "painted drawing" style, often allowing the buffbackground paper to remain uncolored (see illustration of Maharana Amar Singh II with Ladies of the Zenana outside the Picture Hall at Rajnagar).

[81] Prior to that time, Mewar court painters primarily produced manuscripts, and some portraits, and used a flat application of primary colors, with almost no shading, little or no perspective and showed only limited consideration for realistic representation.

Under Sangram Singh II (r. 1710-1734), scenes of darbars, festivals, hunts, temple visits, animal fights and other spectacles became ever larger and more populous and detailed, providing a comprehensive record of the ruler’s public life and the activities of his court".

[7][82] In the reign of Ari Singh (r. 1761–1773) even more of these scenes were painted, "although some artists, including the youthful Bagta, were able to rise above the general level and impose some order on the often chaotic earlier style in the rendition of both landscape and architecture".

Mewar painting, concentrated on court activities of its rulers, existed in a diminished form and with increasing European influence until the abolition of princely powers in 1949 brought an end to royal patronage.

[83] The Kota artists of this period headed by Shaykh Taju were master draftsmen who brushed their animals with the skill of calligraphers and the generally sparse color tones of these pictures allow the superb quality of the draftsmanship to shine through.

Tradition of Marwar painting ended during the reign of Jaswant Singh II (r. 1873–95), a progressive and Western-looking ruler, who in emulation of Victorian England recorded courtly life and the nobles of neighbour states by photograph.

It has been assumed that the classic Kishangarh style resulted from the relationship between Savant Singh (r. 1748–1764), who was a poet and devotee of Krishna, and his uniquely gifted artist, who created lyrical masterpieces in idyllic settings corresponding to the idealized sacred places.

Ragamala sets continued into the new century with an increasing lack of inspiration and Jaipur artists hardened their line and began to favor garishly colored subjects, with considerable influence from Lucknow.

[7] According to Goswamy and Fischer "with their flat, monochromatic backgrounds of rich, saturated yellow or sage green that leave no room for the horizon at the top, and their frenzied, convulsive energy, the paintings of the Ramayana appear to represent a closed, self-contained world.

The borders of those portraits are usually red, and the sitters are set against backgrounds of rich yellow or sage green (see illustration of Raja Ajmat Dev) and seated on colourful floral or striped carpets, which enhance the painting's decorative effect.

"A peculiar idiom for modelling was used by Chamba painters: a series of fine, long lines drawn clearly and at regular intervals on garments was employed for indicating volume, especially of the arms"[7] and it remained in practice for several decades in the 18th century.

[98] According to Goswamy and Fischer Nainsukh's most successful artistic innovation was "his application of Mughal naturalism to details, which imparted to his work an immediacy that was unknown till then in Pahari painting".,[98] but his treatment of space was equally original.

In contrast to earlier Pahari paintings "now the characters in the drama are fully integrated into the landscape or architecture of their surroundings and indeed these hitherto background effects begin to take on an expressive life of their own, complementing or commenting on the action.

In 19th century, Rajput rulers continued to commission sets of paintings illustrating the Hindu epics and religious love poetry, as well as their court life, but with the already mentioned invasions of the Sikhs, Gurkhas, and ultimately British, patronage declined.