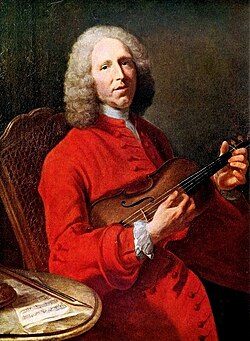

Jean-Philippe Rameau

It was not until the 1720s that he won fame as a major theorist of music with his Treatise on Harmony (1722) and also in the following years as a composer of masterpieces for the harpsichord, which circulated throughout Europe.

His debut, Hippolyte et Aricie (1733), caused a great stir and was fiercely attacked by the supporters of Lully's style of music for its revolutionary use of harmony.

He was educated at the Jesuit college at Godrans in Dijon, but he was not a good pupil and disrupted classes with his singing, later claiming that his passion for opera had begun at the age of twelve.

[6] There, in 1706, he published his earliest-known compositions: the harpsichord works that make up his first book of Pièces de Clavecin, which show the influence of his friend Louis Marchand.

[9] Rameau took his first tentative steps into composing stage music when the writer Alexis Piron asked him to provide songs for his popular comic plays written for the Paris Fairs.

He had already approached writer Antoine Houdar de la Motte for a libretto in 1727, but nothing came of it; he was finally inspired to try his hand at the prestigious genre of tragédie en musique after seeing Montéclair's Jephté in 1732.

Some, such as the composer André Campra, were stunned by its originality and wealth of invention; others found its harmonic innovations discordant and saw the work as an attack on the French musical tradition.

[14] La Poupelinière's salon enabled Rameau to meet some of the leading cultural figures of the day, including Voltaire, who soon began collaborating with the composer.

He received several commissions from the court for works to celebrate the French victory at the Battle of Fontenoy and the marriage of the Dauphin to Infanta Maria Teresa Rafaela of Spain.

[21] Rousseau was a major participant in the second great quarrel that erupted over Rameau's work, the so-called Querelle des Bouffons of 1752–54, which pitted French tragédie en musique against Italian opera buffa.

This time, Rameau was accused of being out of date and his music too complicated in comparison with the simplicity and "naturalness" of a work like Pergolesi's La serva padrona.

The daughter of harpsichord maker Jacques Goermans, she went by the name of Madame de Saint-Aubin, and her opportunistic husband pushed her into the arms of the rich financier.

He lived with his wife and two of his children in his large suite of rooms in Rue des Bons-Enfants, which he would leave every day, lost in thought, to take a solitary walk in the nearby gardens of the Palais-Royal or the Tuileries.

That as due to be followed by a final tragédie en musique, Les Boréades but, for unknown reasons, the opera was never produced and did not get a proper staging unil the late 20th century.

It is difficult to imagine him among the leading wits, including Voltaire (to whom he bears more than a passing physical resemblance[29]), who frequented La Poupelinière's salon; his music was his passport, and it made up for his lack of social graces.

Rameau appeared revolutionary to the Lullyistes, disturbed by complex harmony of his music; and reactionary to the philosophes, who only paid attention to its content and who either would not or could not listen to the sound it made.

The incomprehension Rameau received from his contemporaries stopped him from repeating such daring experiments as the second Trio des Parques in Hippolyte et Aricie, which he was forced to remove after a handful of performances because the singers had been either unable or unwilling to execute it correctly.

Rameau's reworkings of his own material are numerous; e.g., in Les Fêtes d'Hébé, we find L'Entretien des Muses, the Musette, and the Tambourin, taken from the 1724 book of harpsichord pieces, as well as an aria from the cantata Le Berger Fidèle.

[33] For at least 26 years, Rameau was a professional organist in the service of religious institutions, and yet the body of sacred music he composed is exceptionally small and his organ works nonexistent.

[36][37] Along with François Couperin, Rameau was a master of the 18th-century French school of harpsichord music, and both made a break with the style of the first generation of harpsichordists whose compositions adhered to the relatively standardised suite form, which had reached its apogee in the first decade of the 18th century and successive collections of pieces by Louis Marchand, Gaspard Le Roux, Louis-Nicolas Clérambault, Jean-François Dandrieu, Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre, Charles Dieupart and Nicolas Siret.

During his semiretirement (1740 to 1744) he wrote the Pièces de clavecin en concerts (1741), which some musicologists consider the pinnacle of French Baroque chamber music.

Adopting a formula successfully employed by Mondonville a few years earlier, Rameau fashioned these pieces differently from trio sonatas in that the harpsichord is not simply there as basso continuo to accompany melody instruments (violin, flute, viol) but as equal partner in "concert" with them.

Nothing of the kind is to be found in French opera of the day; since Lully, the text had to remain comprehensible—limiting certain techniques such as the vocalise, which was reserved for special words such as gloire ("glory") or victoire ("victory").

A subtle equilibrium existed between the more and the less musical parts: melodic recitative on the one hand and arias that were often closer to arioso on the other, alongside virtuoso "ariettes" in the Italian style.

After the interval of 1740 to 1744, he became the official court musician, and for the most part, composed pieces intended to entertain, with plenty of dance music emphasising sensuality and an idealised pastoral atmosphere.

He made his acquaintance of most of them at La Poupelinière's salon, at the Société du Caveau [fr], or at the house of the comte de Livry, all meeting places for leading cultural figures of the day.

Tommaso Traetta produced two operas setting translations of Rameau libretti that show the French composer's influence, Ippolito ed Aricia (1759) and I Tintaridi (based on Castor et Pollux, 1760).

As Rameau biographer Jean Malignon wrote, "...the German victory over France in 1870–71 was the grand occasion for digging up great heroes from the French past.

"[47] In 1894, composer Vincent d'Indy founded the Schola Cantorum to promote French national music; the society put on several revivals of works by Rameau.

[49] Previous treatises on harmony had been purely practical; Rameau embraced the new philosophical rationalism,[50] quickly rising to prominence in France as the "Isaac Newton of Music".