Rampart Dam

Conservation groups abhorred the threatened flooding of the Yukon Flats, a large area of wetlands that provides a critical breeding ground for millions of waterfowl.

In 1980, U.S. President Jimmy Carter created the Yukon Flats National Wildlife Sanctuary, which formally protected the area from development and disallowed any similar project.

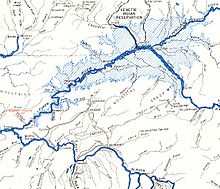

At that point, the river turns west and southwest, flowing through the Yukon Flats, a low-lying wetland area containing thousands of ponds, streams, and other small bodies of water.

[4] In 1944 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers considered building a bridge across Rampart Gorge as part of a project to extend the Alaska Railroad from Fairbanks to Nome to facilitate lend-Lease shipments to the Soviet Union during World War II.

Senator from Alaska Ernest Gruening passed a resolution calling for the Corps of Engineers to begin an official study of the project,[15] and $49,000 was allocated by the federal government for that purpose.

[18] In March 1961, a team of engineers from the Corps' Alaska district began drilling operations at the site to determine bedrock depth and gather other data.

[15] As investigation and planning work continued, the Corps of Engineers reached an agreement with the Department of the Interior, the parent agency of the Bureau of Reclamation, in March 1962.

[20] This agreement negated much of the work of the REAB to that point,[21] as the Interior Department promptly began its own three-year study of the dam's economic feasibility and environmental impact.

[28] In June 1964 the Natural Resources Council asked Stephen H. Spurr, dean of the Graduate School of the University of Michigan and an authority on forestry and forest ecology, to form a group to evaluate the proposed Rampart Dam.

[37] Owing to the large size of the reservoir, engineers estimated that the diversion tunnels would be closed in the 13th year, allowing construction to pace the filling of the new lake.

[45] From the initial planning stages, proponents and opponents speculated that the large size of the reservoir created by the dam could affect the weather in Interior Alaska and the Yukon.

"[50] In early September 1963, a group of Alaska businesspeople, local government leaders, and industry representatives met at McKinley Park Lodge to organize lobbying efforts in favor of the dam.

[52] Alaska senator Ernest Gruening remained a staunch backer of the project from its inception to its cancellation, and made it a major personal political priority.

[57] Gruening, in particular, believed that the dam would have an effect similar to that of the Tennessee Valley Authority in the 1930s, with cheap electricity providing the economic basis of the region.

"[58] Supporters of the project suggested that the cheap electricity provided by the dam would be a strong enticement for electricity-intensive industries, such as aluminum smelting, to move to Alaska.

They were encouraged by a 1962 economic feasibility study by the Development and Resources Corporation, which stated that the electricity generated would attract aluminum, magnesium and titanium industries to the region and help process locally produced minerals.

[61] Both the 1962 study, and another report by University of Michigan researcher Michael Brewer in 1966, stated that tens of thousands of jobs would be created by the construction process alone, even if the cheap electricity generated by the dam failed to attract any additional industries to Alaska.

Gruening stated that the project would be similar to Lake Powell, in that it would create a range of recreational activities, including water skiing and picnicking.

[67] Conservation groups opposed the dam's construction because it would flood the Yukon Flats, a large wetland area that provides breeding ground for millions of waterfowl and habitat for game and fur-bearing animals.

[68] This was followed in early 1961 by an Alaska Sportsmen's Council resolution that criticized the Corps of Engineers for reducing its funding for studies of the impact of the project on fish and game stocks.

[70] The California Fish and Game Commission was among the first non-Alaska conservation groups to oppose construction of the dam, saying in 1963 that it would inundate the Yukon Flats, an area of wetlands that is among North America's largest waterfowl breeding grounds.

The report strongly opposed construction of the dam, saying in part: "Nowhere in the history of water development in North America have the fish and wildlife losses anticipated to result from a single project been so overwhelming.

After traveling the Yukon River, Brooks hypothesized that construction of the dam would be catastrophic from an ecological and human standpoint, would cost an exorbitant amount of money, and that the claims of attracting industry and tourism to Alaska were greatly exaggerated.

[74] In real terms, he estimated that construction of the dam would eliminate the habitat for 1.5 million ducks, 12,500 geese, 10,000 cranes, 270,000 salmon, 12,000 moose, and seven percent of Alaska's fur-bearing animals.

[79] The Tundra Times, an Alaska newspaper devoted to Native issues, also came out strongly in opposition to the project, saying that all but one village from the head of the proposed reservoir to the mouth of the Yukon River were against the dam.

In part, it said: "... it may be said that relatively speaking, the archaeological potential of the Rampart Impoundment area is great; the practical difficulties of field work will have to be overcome in order to obviate the possible loss of what may be some of the most important prehistoric records in North America.

[58] In his 1966 analysis of the project's economic feasibility, Michael Brewer refuted the conclusions of the 1962 federal study, saying that the ability of the dam to pay for itself was "an exercise in speculation".

[85] Owing to increasing public pressure, in June 1967, United States Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall announced he was strongly opposed to the dam, citing economic and biological factors as well as the drastic impact on the area's native population.

Rather than becoming focused singularly on solely preserving the natural beauty of a particular landscape, as had inspired the creation of the U.S. National Park Service in the United States during the first half of the twentieth century, naturalists and environmentalists began to consider the human cost of development as well.

[93] Though opposition to Rampart was founded primarily on economic and natural grounds, its consequences for the Alaska Native population in the region reflected later concerns about industrial development in more urban areas.