Ramsay MacDonald

He formed the National Government to carry out spending cuts to defend the gold standard, but it had to be abandoned after the Invergordon Mutiny, and he called a general election in 1931 seeking a "doctor's mandate" to fix the economy.

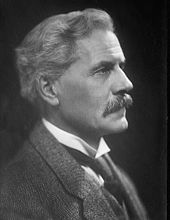

Historian John Shepherd states that "MacDonald's natural gifts of an imposing presence, handsome features and a persuasive oratory delivered with an arresting Highlands accent made him the iconic Labour leader".

Since the 1960s, some historians have defended his reputation, emphasising his earlier role in building up the Labour Party, dealing with the Great Depression, and as a forerunner of the political realignments of the 1990s and 2000s.

[6] In 1885, he moved to Bristol to take up a position as an assistant to Mordaunt Crofton, a clergyman who was attempting to establish a Boys' and Young Men's Guild at St Stephen's Church.

[10] Following a short period of work addressing envelopes at the National Cyclists' Union in Fleet Street, he found himself unemployed and forced to live on the small amount of money he had saved from his time in Bristol.

[15] However, MacDonald never lost his interest in Scottish politics and home rule, and in Socialism: critical and constructive, published in 1921, he wrote: "The Anglification of Scotland has been proceeding apace to the damage of its education, its music, its literature, its genius, and the generation that is growing up under this influence is uprooted from its past.

Although not wealthy, Margaret MacDonald was comfortably well off,[30] and this allowed them to indulge in foreign travel, visiting Canada and the United States in 1897, South Africa in 1902, Australia and New Zealand in 1906 and India several times.

It was during this period that MacDonald and his wife began a long friendship with the social investigator and reforming civil servant Clara Collet[31][32] with whom he discussed women's issues.

He was the chief intellectual leader of the party, paying little attention to class warfare and much more to the emergence of a powerful state as it exemplified the Darwinian evolution of an ever more complex society.

[39] After the Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, warned the House of Commons on 3 August that war with Germany was likely, MacDonald responded by declaring that "this country ought to have remained neutral".

[49] As the war dragged on, his reputation recovered but he still lost his seat in the 1918 "Coupon Election", which saw the Liberal David Lloyd George's coalition government win a large majority.

"[57] MacDonald became noted for "woolly" rhetoric such as the occasion at the Labour Party Conference of 1930 at Llandudno when he appeared to imply unemployment could be solved by encouraging the jobless to return to the fields "where they till and they grow and they sow and they harvest".

King George V noted in his diary, "He wishes to do the right thing.... Today, 23 years ago, dear Grandmama [Queen Victoria] died.

[67] In June 1924, MacDonald convened a conference in London of the wartime Allies and achieved an agreement on a new plan for settling the reparations issue and French-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr.

[68] MacDonald, who accepted the popular view of the economist John Maynard Keynes of German reparations as impossible to pay, pressured French Premier Édouard Herriot until many concessions were made to Germany, including the evacuation of the Ruhr.

On 29 October 1924, the 1924 United Kingdom general election was held and the Conservative Party under Stanley Baldwin was returned decisively, gaining 155 seats for a total of 413 members of parliament.

However, an attempt by the Education Minister Charles Trevelyan to introduce an act to raise the school-leaving age to 15 was defeated by opposition from Roman Catholic Labour MPs, who feared that the costs would lead to increasing local authority control over faith schools.

[65] In international affairs, he also convened the Round Table conferences in London with the political leaders of India, at which he offered them responsible government, but not independence or even Dominion status.

Philip Snowden was a rigid exponent of orthodox finance and would not permit any deficit spending to stimulate the economy, despite the urgings of Oswald Mosley, David Lloyd George and the economist John Maynard Keynes.

Under pressure from its Liberal allies, as well as the Conservative opposition who feared that the budget was unbalanced, Snowden appointed a committee headed by Sir George May to review the state of public finances.

[85] Although there was a narrow majority in the Cabinet for drastic reductions in spending, the minority included senior ministers such as Arthur Henderson who made it clear they would resign rather than acquiesce in the cuts.

With this unworkable split, on 24 August 1931, MacDonald submitted his resignation and then agreed, on the urging of King George V, to form a National Government with the Conservatives and Liberals.

In control of domestic policy were Conservatives Stanley Baldwin as Lord President and Neville Chamberlain the chancellor of the exchequer, together with National Liberal Walter Runciman at the Board of Trade.

[89] MacDonald, Chamberlain and Runciman devised a compromise tariff policy, which stopped short of protectionism while ending free trade and, at the 1932 Ottawa Conference, cementing commercial relations within the Commonwealth.

[96][page needed] MacDonald was aware of his fading powers, and in 1935 he agreed to a timetable with Baldwin to stand down as Prime Minister after King George V's Silver Jubilee celebrations in May 1935.

A sea voyage (with his youngest daughter Sheila) was recommended to restore MacDonald's health, but he died of heart failure on board the liner MV Reina del Pacifico, on 9 November 1937, aged 71.

MacDonald's coffin was borne on a gun carriage to the Church of England's Cathedral of the Most Holy Trinity, in a procession that included the ship's company of Orion and a detachment of the Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment), serving in the Bermuda Garrison.

After cremation, his ashes were taken to Lossiemouth, where a service commenced in his house, The Hillocks, followed by a procession to Holy Trinity Church, Spynie, where they were buried alongside his wife Margaret and their son David in his native Moray.

[106] Another son, Alister Gladstone MacDonald (1898–1993) was a conscientious objector in the First World War, serving in the Friends' Ambulance Unit; he became a prominent architect who worked on promoting the planning policies of his father's government, and specialised in cinema design.

[107] MacDonald was devastated by Margaret's death from blood poisoning in 1911, and had few significant personal relationships after that time, apart from with Ishbel, who acted as his consort while he was Prime Minister and cared for him for the rest of his life.

Mr. Ramsay MacDonald ( Champion of Independent Labour ). "Of course I'm all for peaceful picketing—on principle. But it must be applied to the proper parties."

Cartoon from Punch 20 June 1917