Rashi

Acclaimed for his ability to present the basic meaning of the text in a concise and lucid fashion, Rashi's commentaries appeal to both learned scholars and beginning students, and his works remain a centerpiece of contemporary Torah study.

A large fraction of rabbinic literature published since the Middle Ages discusses Rashi, either using his view as supporting evidence or debating against it.

[8] In 1839, Leopold Zunz[9] showed that the Hebrew usage of Jarchi was an erroneous propagation of the error by Christian writers, instead he interpreted the abbreviation as: Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki.

Rashi's father, Yitzhak, a poor winemaker, once found a precious jewel and was approached by non-Jews who wished to buy it to adorn their idol.

Afterwards he was visited by either the Voice of God or the prophet Elijah, who told him that he would be rewarded with the birth of a noble son "who would illuminate the world with his Torah knowledge.

One text goes so far as to claim that Rashi was beyond human; the author proposes that he never died a natural death, but rather ascended to Heaven alive like the immortal prophet Elijah.

At the age of 17 he married and soon after went to learn in the yeshiva of Yaakov ben Yakar in Worms, returning to his wife three times yearly, for the Days of Awe, Passover and Shavuot.

Rashi's teachers were students of Rabbeinu Gershom and Eliezer Hagadol, leading Talmudists of the previous generation.

Upon the death of the head of the Bet din, Zerach ben Abraham, Rashi assumed the court's leadership and answered hundreds of halakhic queries.

[23] The only reason given for the centuries-old tradition that he was a vintner being not true is that the soil in all of Troyes is not optimal for growing wine grapes, claimed by the research of Haym Soloveitchik.

Rashi wrote several Selichot (penitential poems) mourning the slaughter and the destruction of the region's great yeshivot.

A number of years ago, a Sorbonne professor discovered an ancient map depicting the site of the cemetery, which lay under an open square in the city of Troyes.

In 2005, Yisroel Meir Gabbai erected an additional plaque at this site marking the square as a burial ground.

It opens the heart and uncovers one's essential love and fear of G-d."[33] Scholars believe that Rashi's commentary on the Torah grew out of the lectures he gave to his students in his yeshiva, and evolved with the questions and answers they raised on it.

[38] A portion of his writing is dedicated to making distinctions between the peshat, or plain and literal meaning of the text, and the aggadah or rabbinic interpretation.

Rashbam, one of Rashi's grandchildren, heavily critiqued his response on his "commentary on the Torah [being] based primarily on the classic midrashim (rabbinic homilies).

As in his commentary on the Tanakh, Rashi frequently illustrates the meaning of the text using analogies to the professions, crafts, and sports of his day.

This is true of Makkot (the end of which was composed by his son-in-law, Judah ben Nathan), and of Bava Batra (finished, in a more detailed style, by his grandson the Rashbam).

Although some may find contradictory to Rashi's intended purpose for his writings, these responsa were copied, preserved, and published by his students, grandchildren, and other future scholars.

[48] Some say that his responsa allows people to obtain "clear pictures of his personality," and shows Rashi as a kind, gentle, humble, and liberal man.

Rashi's responsa not only addressed some of the different cases and questions regarding Jewish life and law, but it shed light into the historical and social conditions which the Jews were under during the First Crusade.

[47] For example, in his writing regarding relations with the Christians, he provides a guide for how one should behave when dealing with martyrs and converts, as well as the "insults and terms of [disgrace] aimed at the Jews.

"[47] Stemming from the aftermath of the Crusades, Rashi wrote concerning those who were forced to convert, and the rights women had when their husbands were killed.

[58] Tens of thousands of men, women and children study "Chumash with Rashi" as they review the Torah portion to be read in synagogue on the upcoming Shabbat.

[62] Voluminous supercommentaries have been published on Rashi's Bible commentaries, including Gur Aryeh by Judah Loew (the Maharal), Sefer ha-Mizrachi by Elijah Mizrachi (the Re'em), and Yeri'ot Shlomo by Solomon Luria (the Maharshal).

The lifelong study of Talmud, the constant conquest of new tractates, and the unlimited personal acquisition of knowledge was in many ways the consequence of Rashi’s inimitable work of exposition.

Yet, all realized that the problem that had confronted scholars for close to half a millennium—how to turn the abrupt and sometimes gnomic formulations of the Talmud into a coherent and smoothly flowing text—had been solved definitively by Rashi.

[65] This addition to Jewish texts was seen as causing a "major cultural product"[66] which became an important part of Torah study.

Errors often crept in: sometimes a copyist would switch words around, and other times incorporate a student's marginal notes into the main text.

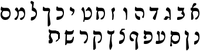

Early Hebrew typographers such as the Soncino family and Daniel Bomberg employed in their editions of commented texts (such as the Mikraot Gedolot and the Talmud, in which Rashi's commentaries prominently figure) what would become called "Rashi script" to distinguish the rabbinic commentary from the primary text proper, for which they used a square typeface.