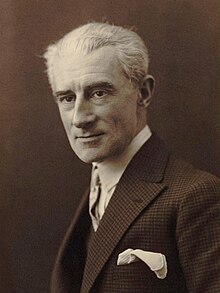

Maurice Ravel

Born to a music-loving family, Ravel attended France's premier music college, the Paris Conservatoire; he was not well regarded by its conservative establishment, whose biased treatment of him caused a scandal.

After leaving the conservatoire, Ravel found his own way as a composer, developing a style of great clarity and incorporating elements of modernism, baroque, neoclassicism and, in his later works, jazz.

Some of his piano music, such as Gaspard de la nuit (1908), is exceptionally difficult to play, and his complex orchestral works such as Daphnis et Chloé (1912) require skilful balance in performance.

"[14] There is no record that Ravel received any formal general schooling in his early years; his biographer Roger Nichols suggests that the boy may have been chiefly educated by his father.

[15] When he was seven, Ravel started piano lessons with Henri Ghys, a friend of Emmanuel Chabrier; five years later, in 1887, he began studying harmony, counterpoint and composition with Charles-René, a pupil of Léo Delibes.

His works from the period include the songs "Un grand sommeil noir" and "D'Anne jouant de l'espinette" to words by Paul Verlaine and Clément Marot,[18][n 6] and the piano pieces Menuet antique and Habanera (for four hands), the latter eventually incorporated into the Rapsodie espagnole.

[46] Orenstein comments that, short in stature,[n 9] light in frame and bony in features, Ravel had the "appearance of a well-dressed jockey", whose large head seemed suitably matched to his formidable intellect.

Ravel, together with his close friend and confidante Misia Edwards and the opera star Lucienne Bréval, contributed to a modest regular income for the deserted Lilly Debussy, a fact that Nichols suggests may have rankled with her husband.

During the first years of the new century Ravel made five attempts to win France's most prestigious prize for young composers, the Prix de Rome, past winners of which included Berlioz, Gounod, Bizet, Massenet and Debussy.

[68] The press's indignation grew when it emerged that the senior professor at the Conservatoire, Charles Lenepveu, was on the jury, and only his students were selected for the final round;[69] his insistence that this was pure coincidence was not well received.

As the guest of the Vaughan Williamses, he visited London, where he played for the Société des Concerts Français, gaining favourable reviews and enhancing his growing international reputation.

[119] Ravel declined to join, telling the committee of the league in 1916, "It would be dangerous for French composers to ignore systematically the productions of their foreign colleagues, and thus form themselves into a sort of national coterie: our musical art, which is so rich at the present time, would soon degenerate, becoming isolated in banal formulas.

The Société presented concerts of recent works by American composers including Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson and George Antheil and by Vaughan Williams and his English colleagues Arnold Bax and Cyril Scott.

[140] A ballet danced to the orchestral version of Le tombeau de Couperin was given at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in November 1920, and the premiere of La valse followed in December.

[149] His other major works from the 1920s include the orchestral arrangement of Mussorgsky's piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition (1922), the opera L'enfant et les sortilèges[n 27] to a libretto by Colette (1926), Tzigane (1924) and the Violin Sonata No.2 (1927).

"[152] Orenstein, commenting that this tour marked the zenith of Ravel's international reputation, lists its non-musical highlights as a visit to Poe's house in New York, and excursions to Niagara Falls and the Grand Canyon.

[178] Though that total is small in comparison with the output of his major contemporaries,[n 32] it is nevertheless inflated by Ravel's frequent practice of writing works for piano and later rewriting them as independent pieces for orchestra.

La cloche engloutie after Hauptmann's The Sunken Bell occupied him intermittently from 1906 to 1912, Ravel destroyed the sketches for both these works, except for a "Symphonie horlogère" which he incorporated into the opening of L'heure espagnole.

Nichols comments that the essential Spanish colouring gave Ravel a reason for virtuoso use of the modern orchestra, which the composer considered "perfectly designed for underlining and exaggerating comic effects".

[194] Edward Burlingame Hill found Ravel's vocal writing particularly skilful in the work, "giving the singers something besides recitative without hampering the action", and "commenting orchestrally upon the dramatic situations and the sentiments of the actors without diverting attention from the stage".

[213] The critics Edward Sackville-West and Desmond Shawe-Taylor comment that in the slow movement, "one of the most beautiful tunes Ravel ever invented", the composer "can truly be said to join hands with Mozart".

[216] Kelly remarks on its "dazzling array of instrumental colour",[18] and a contemporary reviewer commented on how, in dealing with another composer's music, Ravel had produced an orchestral sound wholly unlike his own.

[217] Although Ravel wrote fewer than thirty works for the piano, they exemplify his range; Orenstein remarks that the composer keeps his personal touch "from the striking simplicity of Ma mère l'Oye to the transcendental virtuosity of Gaspard de la nuit".

[220] The authors of The Record Guide consider that works such as Gaspard de la Nuit and Miroirs have a beauty and originality with a deeper inspiration "in the harmonic and melodic genius of Ravel himself".

It involves subtle musicianship, a feeling for pianistic colour and the sort of lightly worn virtuosity that masks the advanced technical challenges he makes in Alborada del gracioso ... and the two outer movements of Gaspard de la nuit.

"[223] This balance caused a breach between the composer and Viñes, who said that if he observed the nuances and speeds Ravel stipulated in Gaspard de la nuit, "Le gibet" would "bore the audience to death".

Like the Debussy, it differs from the more monumental quartets of the established French school of Franck and his followers, with more succinct melodies, fluently interchanged, in flexible tempos and varieties of instrumental colour.

It contains Basque, Baroque and far Eastern influences, and shows Ravel's growing technical skill, dealing with the difficulties of balancing the percussive piano with the sustained sound of the violin and cello, "blending the two disparate elements in a musical language that is unmistakably his own," in the words of the commentator Keith Anderson.

[236] In 1913 there was a gramophone recording of Jeux d'eau played by Mark Hambourg, and by the early 1920s there were discs featuring the Pavane pour une infante défunte and Ondine, and movements from the String Quartet, Le tombeau de Couperin and Ma mère l'Oye.

[246] In his later years, Edouard Ravel declared his intention to leave the bulk of the composer's estate to the city of Paris for the endowment of a Nobel Prize in music, but evidently changed his mind.