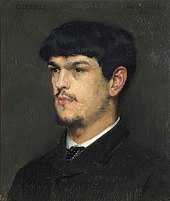

Claude Debussy

[10] In 1870, to escape the siege of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War, Debussy's pregnant mother took him and his sister Adèle to their paternal aunt's home in Cannes, where they remained until the following year.

He first joined the piano class of Antoine François Marmontel,[14] and studied solfège with Albert Lavignac and, later, composition with Ernest Guiraud, harmony with Émile Durand, and organ with César Franck.

[10] With Marmontel's help Debussy secured a summer vacation job in 1879 as resident pianist at the Château de Chenonceau, where he rapidly acquired a taste for luxury that was to remain with him all his life.

Whether Vasnier was content to tolerate his wife's affair with the young student or was simply unaware of it is not clear, but he and Debussy remained on excellent terms, and he continued to encourage the composer in his career.

In May 1893 Debussy attended a theatrical event that was of key importance to his later career – the premiere of Maurice Maeterlinck's play Pelléas et Mélisande, which he immediately determined to turn into an opera.

He expressed trenchant views on composers ("I hate sentimentality – his name is Camille Saint-Saëns"), institutions (on the Paris Opéra: "A stranger would take it for a railway station, and, once inside, would mistake it for a Turkish bath"), conductors ("Nikisch is a unique virtuoso, so much so that his virtuosity seems to make him forget the claims of good taste"), musical politics ("The English actually think that a musician can manage an opera house successfully!

[51] In 1903 there was public recognition of Debussy's stature when he was appointed a Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur,[51] but his social standing suffered a great blow when another turn in his private life caused a scandal the following year.

[51] On 14 October, five days before their fifth wedding anniversary, Lilly Debussy attempted suicide, shooting herself in the chest with a revolver;[51][n 11] she survived, although the bullet remained lodged in her vertebrae for the rest of her life.

[83] He also had a fierce enemy at this period in the form of Camille Saint-Saëns, who in a letter to Fauré condemned Debussy's En blanc et noir: "It's incredible, and the door of the Institut [de France] must at all costs be barred against a man capable of such atrocities".

Debussy's body was reinterred the following year in the small Passy Cemetery sequestered behind the Trocadéro, fulfilling his wish to rest "among the trees and the birds"; his wife and daughter are buried with him.

His friend Georges Jean-Aubry commented that Debussy "admirably imitated Massenet's melodic turns of phrase" in the cantata L'enfant prodigue (1884) which won him the Prix de Rome.

[91] A more characteristically Debussian work from his early years is La Damoiselle élue, recasting the traditional form for oratorios and cantatas, using a chamber orchestra and a small body of choral tone and using new or long-neglected scales and harmonies.

[91] His early mélodies, inspired by Marie Vasnier, are more virtuosic in character than his later works in the genre, with extensive wordless vocalise; from the Ariettes oubliées (1885–1887) onwards he developed a more restrained style.

[92] The musicologist Jacques-Gabriel Prod'homme wrote that, together with La Demoiselle élue, the Ariettes oubliées and the Cinq poèmes de Charles Baudelaire (1889) show "the new, strange way which the young musician will hereafter follow".

But the work as a whole is distinctive, and the first in which we get a hint of the Debussy we were to know later – the lover of vague outlines, of half-lights, of mysterious consonances and dissonances of colour, the apostle of languor, the exclusivist in thought and in style.

Some critics thought the treatment less subtle and less mysterious than his previous works, and even a step backward; others praised its "power and charm", its "extraordinary verve and brilliant fantasy", and its strong colours and definite lines.

[103] The former follows the tripartite form established in the Nocturnes and La mer, but differs in employing traditional British and French folk tunes, and in making the central movement, "Ibéria", far longer than the outer ones, and subdividing it into three parts, all inspired by scenes from Spanish life.

The analyst Richard Langham Smith writes that Impressionism was originally a term coined to describe a style of late 19th-century French painting, typically scenes suffused with reflected light in which the emphasis is on the overall impression rather than outline or clarity of detail, as in works by Monet, Pissarro, Renoir and others.

[108] Langham Smith writes that the term became transferred to the compositions of Debussy and others which were "concerned with the representation of landscape or natural phenomena, particularly the water and light imagery dear to Impressionists, through subtle textures suffused with instrumental colour".

With the latter in mind the composer wrote to the violinist Eugène Ysaÿe in 1894 describing the orchestral Nocturnes as "an experiment in the different combinations that can be obtained from one colour – what a study in grey would be in painting.

Lockspeiser calls La mer "the greatest example of an orchestral Impressionist work",[113] and more recently in The Cambridge Companion to Debussy Nigel Simeone comments, "It does not seem unduly far-fetched to see a parallel in Monet's seascapes".

[115] In 1983 the pianist and scholar Roy Howat published a book contending that certain of Debussy's works are proportioned using mathematical models, even while using an apparent classical structure such as sonata form.

Writing in 1958, the critic Rudolph Reti summarised six features of Debussy's music, which he asserted "established a new concept of tonality in European music": the frequent use of lengthy pedal points – "not merely bass pedals in the actual sense of the term, but sustained 'pedals' in any voice"; glittering passages and webs of figurations which distract from occasional absence of tonality; frequent use of parallel chords which are "in essence not harmonies at all, but rather 'chordal melodies', enriched unisons", described by some writers as non-functional harmonies; bitonality, or at least bitonal chords; use of the whole-tone and pentatonic scales; and unprepared modulations, "without any harmonic bridge".

[2] The piano piece Golliwogg's Cakewalk, from the 1908 suite Children's Corner, contains a parody of music from the introduction to Tristan, in which, in the opinion of the musicologist Lawrence Kramer, Debussy escapes the shadow of the older composer and "smilingly relativizes Wagner into insignificance".

He was for the most part enthusiastic about Richard Strauss[137] and Stravinsky, respectful of Mozart and was in awe of Bach, whom he called the "good God of music" (le Bon Dieu de la musique).

"[143] In 1915 he complained that "since Rameau we have had no purely French tradition [...] We tolerated overblown orchestras, tortuous forms [...] we were about to give the seal of approval to even more suspect naturalizations when the sound of gunfire put a sudden stop to it all."

They favoured poetry using suggestion rather than direct statement; the literary scholar Chris Baldrick writes that they evoked "subjective moods through the use of private symbols, while avoiding the description of external reality or the expression of opinion".

As well as Maeterlinck for Pelléas et Mélisande, he drew on Shakespeare and Dickens for two of his Préludes for piano – La Danse de Puck (Book 1, 1910) and Hommage à S. Pickwick Esq.

Their sympathiser and self-appointed spokesman Jean Cocteau wrote in 1918: "Enough of nuages, waves, aquariums, ondines and nocturnal perfumes," pointedly alluding to the titles of pieces by Debussy.

[163][n 19] In 1904, Debussy played the piano accompaniment for Mary Garden in recordings for the Compagnie française du Gramophone of four of his songs: three mélodies from the Verlaine cycle Ariettes oubliées – "Il pleure dans mon coeur", "L'ombre des arbres" and "Green" – and "Mes longs cheveux", from Act III of Pelléas et Mélisande.