Raven banner

The raven banner (Old Norse: hrafnsmerki [ˈhrɑvnsˌmerke]; Middle English: hravenlandeye) was a flag, possibly totemic in nature, flown by various Viking chieftains and other Scandinavian rulers during the 9th, 10th and 11th centuries.

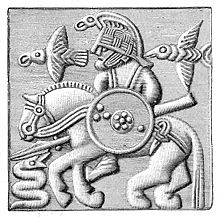

Norse and European period artwork, however, depicts war banners[citation needed] as roughly triangular, with a rounded outside edge on which there hung a series of tabs or tassels, some with a resemblance to ornately carved "weather-vanes" used aboard Viking longships, indicating that some raven banners may have been constructed in a similar manner.

The highest god Odin had two ravens named Huginn and Muninn ("thought" and "memory" respectively) who flew around the world bringing back tidings to their master.

Þá sendir hann í dagan at fljúga um heim allan, ok koma þeir aftr at dögurðarmáli.

Því kalla menn hann Hrafnaguð, svá sem sagt er: Two ravens sit on Odin's shoulders, and bring to his ears all that they hear and see.

[6] An example of this is found in Norna-Gests þáttr, where Regin recites the following poem after Sigurd kills the sons of Hunding: Nú er blóðugr örn breiðum hjörvi bana Sigmundar á baki ristinn.

[10] In black flocks, the ravens hover over the corpses and the skald asks where they are heading (Hvert stefni þér hrafnar hart með flokk hinn svarta).

[12] He flies from the field of battle with blood on his beak, human flesh in his talons and the reek of corpses from his mouth (Með dreyrgu nefi, hold loðir í klóum en hræs þefr ór munni).

[14] and "the ravens shall tear out your eyes in the high gallows" (Hrafnar skulu þér á hám galga slíta sjónir ór).

Despite the violent imagery associated with them, early Scandinavians regarded the raven as a largely positive figure; battle and harsh justice were viewed favorably in Norse culture.

The war banner (guþfana) which they called "Raven" was also taken.The 12th-century Annals of St Neots claims that a raven banner was present with the Great Heathen Army and adds insight into its seiðr- (witchcraft-) influenced creation and totemic and oracular nature: Dicunt enim quod tres sorores Hynguari et Hubbe, filie uidelicet Lodebrochi, illud uexillum tex'u'erunt et totum parauerunt illud uno meridiano tempore.

Dicunt etiam quod, in omni bello ubi praecederet idem signum, si uictoriam adepturi essent, appareret in medio signi quasi coruus uiuus uolitans; si uero uincendi in futuro fuissent, penderet directe nichil mouens – et hoc sepe probatum est[20] It is said that three sisters of Hingwar and Habba [Ivar and Ubbe], i.e., the daughters of Ragnar Loðbrok, had woven that banner and gotten it ready during one single midday's time.

Many of the Norse-Gaelic dynasts in Britain and Ireland were of the Uí Ímair clan, which claimed descent from Ragnar Lodbrok through his son Ivar.

[27] The army of King Cnut the Great of England, Norway and Denmark bore a raven banner made from white silk at the Battle of Ashingdon in 1016.

I am well aware that this may seem incredible to the reader, but nevertheless I insert it in my veracious work because it is true: This banner was woven of the cleanest and whitest silk and no picture of any figures was found on it.

[28] The Lives of Waltheof and his Father Sivard Digri (The Stout), the Earl of Northumberland, written by a monk of Crowland Abbey (possibly the English historian William of Ramsey), reports that the Danish jarl of Northumbria, Sigurd, was given a banner by an unidentified old sage.

Harald's Saga relates that when King Haraldr saw that the battle array of the English had come down along the ditch right opposite them, he had the trumpets blown and sharply urged his men to the attack, raising his banner called Landøyðan.

After Harald was struck by an arrow and killed, his army fought fiercely for possession of the banner, and some of them went berserk in their frenzy to secure the flag.

[32] Other than the dragon banner of Olaf II of Norway, the Landøyðan of Harald Hardrada is the only early Norwegian royal standard described by Snorri Sturluson in the Heimskringla.

[33] In two panels of the famous Bayeux tapestry, standards are shown which appear to potentially be raven banners (although one is small and not given a motif).

In a second, depicting the deaths of Harold Godwinson's brothers, a triangular banner closely resembling that shown on Olaf Cuaran's coin lies broken on the ground.