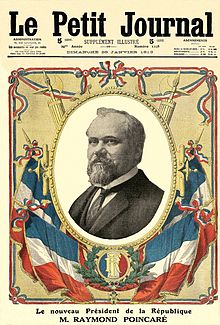

Raymond Poincaré

By this time Poincaré was seen, especially in the English-speaking world, as an aggressive figure (Poincaré-la-Guerre) who had helped to cause the war in 1914 and who now favoured punitive anti-German policies.

Along with other followers of "Opportunist" Léon Gambetta, Poincaré founded the Democratic Republican Alliance (ARD) in 1902, which became the most important centre-right party under the Third Republic.

The British historian, Anthony Adamthwaite, described Poincaré as having an "obsession with Clemenceau verging on paranoia" and as a "cold fish whose one passion was cats".

[7] Poincaré became Prime Minister in January 1912, and began a policy meant to block Germany's ambitions for "world power status", and worked to restore ties with France's ally, Russia.

[13] The Russian Foreign Minister, Sergey Sazonov, in a report to Nicholas wrote that, after meeting Poincaré: "Russia possesses a sure and faithful friend, endowed with a political spirit above the line and an inflexible will.".

[14] At the same time, Poincaré favoured hoped to pursue an expansionist policy at the expense of Germany's unofficial ally, the Ottoman Empire.

Poincaré was a leading member of the Comité de l'Orient, the main group that advocated French expansionism in the Middle East.

[8] Bulgaria's swift victory over the Ottomans was a great blow to German prestige, and correspondingly boosted French confidence, something that allowed Poincaré to approach Berlin from a position of strength.

Poincaré therefore rejected Caillaux's proposal for a Franco-German alliance, arguing that Paris would be the junior partner, thus tantamount to ending France's status as a great power.

[16] Poincaré's entire foreign policy was based on the old Roman saying si vis pacem, para bellum ("if you want peace, prepare for war").

He wanted to strengthen both France and Russia to such a point that they presented such a decisive margin of superiority as to deter Germany from going to war with either power, but at same time his foreign policy was not relentlessly anti-German.

[18] His speeches warned of the "German menace" and believed Caillaux's policy of rapprochement with Berlin would create an impression of French weakness in Wilhelm II's mind, being a man who only respected the strong.

No ideologue, he was a practical politician willing to work with any true Frenchmen but adamant in defending France from the Socialist Left, the Catholic Right and, of course, Germany".

[20] The President remarked that the assassination was a tragedy, ordered an aide to draft a message of condolence to the people of Austria-Hungary and stayed on to enjoy the rest of the races.

When the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum was presented to Serbia on 23 July, the French government was in the hands of Jean-Baptiste Bienvenu-Martin, Minister of Justice and acting Premier.

Bienvenu-Martin's inability to make decisions was especially exasperating to Philippe Berthelot, the most senior man in the Quai d'Orsay present in Paris, who complained that France was doing nothing while Europe was threatened with the prospect of war.

[23] It was not until Poincaré had arrived back in Paris on 30 July 1914 that he finally learned of the crisis, and immediately attempted to stop matters from escalating into war.

[25] The next day, 31 July, the German ambassador in Paris, Count Wilhelm von Schoen, presented to Viviani an ultimatum warning that, if Russian mobilisation continued, Germany would attack both France and Russia within the next 12 hours.

"[30] « Dans la guerre qui s'engage, la France […] sera héroïquement défendue par tous ses fils, dont rien ne brisera devant l'ennemi l'union sacrée » ("In the coming war, France will be heroically defended by all its sons, whose sacred union will not break in the face of the enemy").

[31] At the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, negotiating the Treaty of Versailles, he wanted France to wrest the Rhineland from Germany to put it under Allied military control.

[32][33] Ferdinand Foch urged Poincaré to invoke his powers as laid down in the constitution and take over the negotiations of the treaty due to worries that Clemenceau was not achieving France's aims.

[36] Frustrated at Germany's unwillingness to pay reparations, Poincaré hoped for joint Anglo-French economic sanctions against it in 1922, while opposing military action.

He was disturbed that British Prime Minister David Lloyd George did not share the French viewpoint, instead almost welcoming Rapallo as a chance to bring Soviet Russia into the international system.

[38] Further adding to Poincaré's fears was the worldwide propaganda campaign started in April 1922 blaming France for World War I as a means of disproving Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles, which would thereby undermine the French claim to reparations.

[40] The French Communist newspaper L'Humanité ran a front-page cover-story accusing Poincaré and Nicholas II of being the two men who plunged the world into war in 1914.

[43] By December 1922 Poincaré was faced with British-American-German hostility and saw coal for French steel production and money for reconstructing the devastated industrial areas draining away.

[51][52] His popularity as prime minister rose considerably following his return to the gold standard, so much so that his party won the April 1928 general election.