Red-giant branch

Red-giant-branch stars have an inert helium core surrounded by a shell of hydrogen fusing via the CNO cycle.

Although the basis of a thermonuclear main-sequence lifetime, followed by a thermodynamic contraction phase to a white dwarf was understood by 1940, the internal details of the various types of giant stars were not known.

[4] Observations of a bifurcated giant branch had been made years earlier but it was unclear how the different sequences were related.

[8] Modern stellar physics has modelled the internal processes that produce the different phases of the post-main-sequence life of moderate-mass stars,[9] with ever-increasing complexity and precision.

Any additional energy production from the shell fusion is consumed in inflating the envelope and the star cools but does not increase in luminosity.

The hydrogen shell, fusing via the temperature-sensitive CNO cycle, greatly increases its rate of energy production and the stars is considered to be at the foot of the red-giant branch.

For a star the same mass as the sun, this takes approximately 2 billion years from the time that hydrogen was exhausted in the core.

[14][15] Stars at the foot of the red-giant branch all have a similar temperature around 5,000 K, corresponding to an early to mid-K spectral type.

[16] As their hydrogen shells continue to produce more helium, the cores of RGB stars increase in mass and temperature.

Shell energy production temporarily decreases at this discontinuity, effective stalling the ascent of the RGB and causing an excess of stars at that point.

All stars that reach this point have an identical helium core mass of almost 0.5 M☉, and very similar stellar luminosity and temperature.

These stars become hot enough to start triple-alpha fusion before they reach the tip of the red-giant branch and before the core becomes degenerate.

Stars only a little more massive than 2 M☉ perform a barely noticeable blue loop at a few hundred L☉ before continuing on the AGB hardly distinguishable from their red-giant branch position.

Also shown are the helium core mass, surface effective temperature, radius and luminosity at the start and end of the RGB for each star.

[26][27] Mass lost by more massive stars that leave the red-giant branch before the helium flash is more difficult to measure directly.

The current mass of Cepheid variables such as δ Cephei can be measured accurately because there are either binaries or pulsating stars.

When compared with evolutionary models, such stars appear to have lost around 20% of their mass, much of it during the blue loop and especially during pulsations on the instability strip.

Some of these correspond to the known Miras and semi-regulars, but an additional class of variable star has been defined: OGLE Small Amplitude Red Giants, or OSARGs.

The cause of the long secondary periods is unknown, but it has been proposed that they are due to interactions with low-mass companions in close orbits.

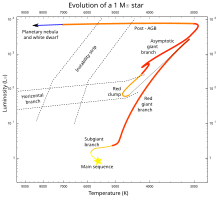

- the 0.6 M ☉ track shows the RGB and stops at the helium flash .

- the 1 M ☉ track shows a short but long-lasting subgiant branch and the RGB to the helium flash.

- the 2 M ☉ track shows the subgiant branch and RGB, with a barely detectable blue loop onto the AGB .

- the 5 M ☉ track shows a long but very brief subgiant branch, a short RGB and an extended blue loop.