Red giant

Despite the lower energy density of their envelope, red giants are many times more luminous than the Sun because of their great size.

[1] The first dredge-up occurs during hydrogen shell burning on the red-giant branch, but does not produce a large carbon abundance at the surface.

The second, and sometimes third, dredge-up occurs during helium shell burning on the asymptotic-giant branch and convects carbon to the surface in sufficiently massive stars.

[2] The coolest red giants have complex spectra, with molecular lines, emission features, and sometimes masers, particularly from thermally pulsing AGB stars.

[7] Another noteworthy feature of red giants is that, unlike Sun-like stars whose photospheres have a large number of small convection cells (solar granules), red-giant photospheres, as well as those of red supergiants, have just a few large cells, the features of which cause the variations of brightness so common on both types of stars.

The star "enters" the main sequence when its core reaches a temperature (several million kelvins) high enough to begin fusing hydrogen-1 (the predominant isotope), and establishes hydrostatic equilibrium.

Still, the behavior is necessary to satisfy simultaneous conservation of gravitational and thermal energy in a star with the shell structure.

Once the core is degenerate, it will continue to heat until it reaches a temperature of roughly 1×108 K, hot enough to begin fusing helium to carbon via the triple-alpha process.

The ejection of the outer mass and the creation of a planetary nebula finally ends the red-giant phase of the star's evolution.

[9] These "intermediate" stars cool somewhat and increase their luminosity but never achieve the tip of the red-giant branch and helium core flash.

When the ascent of the red-giant branch ends they puff off their outer layers much like a post-asymptotic-giant-branch star and then become a white dwarf.

Eventually the level of helium increases to the point where the star ceases to be fully convective and the remaining hydrogen locked in the core is consumed in only a few billion more years.

[19][20] Although traditionally it has been suggested the evolution of a star into a red giant will render its planetary system, if present, uninhabitable, some research suggests that, during the evolution of a 1 M☉ star along the red-giant branch, it could harbor a habitable zone for several billion years at 2 astronomical units (AU) out to around 100 million years at 9 AU out, giving perhaps enough time for life to develop on a suitable world.

[24] (A similar process in multiple star systems is believed to be the cause of most novas and type Ia supernovas.)

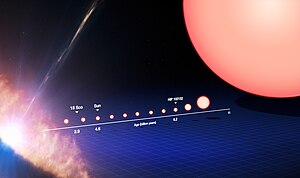

[26] The Sun will exit the main sequence in approximately 5 billion years and start to turn into a red giant.

[29][30] As a red giant, the Sun will grow so large (over 200 times its present-day radius: ~215 R☉; ~1 AU) that it will engulf Mercury, Venus, and likely Earth.