Redistricting

[2] The U.S. Constitution in Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 provides for proportional representation in the House of Representatives.

According to Colegrove v. Green, 328 U.S. 549 (1946), Article I, Section 4 left to the legislature of each state the authority to establish congressional districts;[4] however, such decisions are subject to judicial review.

[8] In recent years, critics have argued that redistricting has been used to neutralize minority voting power.

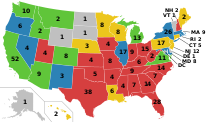

These states do not need redistricting for the House and elect members on a state-wide at-large basis.

[13] To reduce the role that legislative politics might play, thirteen states (Alaska,[a] Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Washington) determine congressional redistricting by an independent or bipartisan redistricting commission.

[14] Five states: Maine, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont,[b] and Virginia give independent bodies authority to propose redistricting plans, but preserve the role of legislatures to approve them.

The previous apportionment acts required districts be contiguous, compact, and equally populated.

[30][31] Some states, including New Jersey and New York, protect incumbents of both parties, reducing the number of competitive districts.

In addition, those disadvantaged by a proposed redistricting plan may challenge it in state and federal courts.