Re-education through labor

Active from 1957 to 2013, the system was used to detain persons who were accused of committing minor crimes such as petty theft, prostitution, and trafficking of illegal drugs, as well as political dissidents, petitioners, and Falun Gong followers.

[2][3] However, human rights groups have claimed that other forms of extrajudicial detention have taken its place, with some former RTL camps being renamed drug rehabilitation centers.

[4] In 2014, re-education facilities were constructed in Xinjiang and they were used to target a wider context than people who were accused of committing minor crimes and political dissidence.

[24] Institutions similar to re-education through labor facilities, but called "new life schools" or "loafers' camps", existed in the early 1950s, although they did not become official until the anti-rightist campaigns in 1957 and 1958.

[30] A report by Human Rights in China (HRIC) states that re-education through labor was first used by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1955 to punish counter-revolutionaries, and in 1957 was officially adopted into law to be implemented by the Ministry of Public Security.

[25][42] A month later, Chongqing municipality passed a law allowing lawyers to offer legal counsel in re-education through labor cases.

[45][46] During the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, there were reports that some individuals who applied for permits to protest were detained without trial;[47] of these, some were sentenced to re-education through labor.

[65] One China specialist at the RAND Corporation has claimed that the police, faced with a lack of "modern rehabilitation and treatment programs," use re-education through labor convictions to "warehouse" individuals for "an increasing number of social problems.

For example, when he was released from a three-year re-education sentence in 1999,[69] dissident Liu Xiaobo said that he had been treated very mildly, that he had been allowed to spend time reading, and that the conditions had been "pretty good.

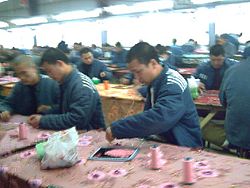

"[60] Forced labor may include breaking rocks and assembling car seat covers, and even gold farming in World of Warcraft.

[70] According to Chinese state media Xinhua, slightly over 50% of detainees released from prison and re-education through labor in 2006 received government aid in the form of funds or assistance in finding jobs.

Individuals who remain in re-education through labor for 5 or more years may not be allowed to return to their homes, and those who do may be closely monitored and not permitted to leave certain areas.

)of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which provides that "Anyone who is deprived of his liberty by arrest or detention shall be entitled to take proceedings before a court, in order that the court may decide without delay on the lawfulness of his detention..."[21] Re-education through labor has also been criticized by numerous human rights groups for not offering procedural guarantees for the accused,[31][34] and for being used to detain political dissidents,[72] teachers,[52][73] Chinese house church leaders,[20] and Falun Gong practitioners.

[31][72] Furthermore, even though the law up until 2007 specified a maximum length of detainment of four years, at least one source mentions a "retention for in-camp employment" system that allowed authorities to keep detainees in the camps for longer than their official sentences.

[21] Re-education through labor has been a focus of discussion not only among foreign human rights groups, but also among legal scholars in China, some of whom were involved in the drafting of the 2007 laws meant to replace the system.

A 1997 report in China's Legal Daily hailed re-education through labor as a means to "maintain social peace and prevent and reduce crime.

[74] During the Third Plenum of the 18th Party Congress in Beijing on 15 November 2013, Chinese officials announced that they planned to abolish the Re-education Through Labor system.

[75][76] The planned abolition of the system, however, has been criticised by human rights groups, with Amnesty International issuing a report titled "Changing the Soup but Not the Medicine."

Amnesty's report concludes that the camp closures are a positive step forward for human rights, but the fundamental problems of arbitrary detention remain in China:[76] Many of the policies and practices which resulted in individuals being punished for peacefully exercising their human rights by sending them to RTL have not fundamentally changed: quite the contrary.

Falun Gong practitioners continue to be punished through criminal prosecution and being sent to "brainwashing centres" and other forms of arbitrary detention.

Petitioners likewise continue to be subjected to harassment, forcibly committed to mental institutions and sent to "black jails" and other forms of arbitrary detention.