Referendum Party

Ultimately the party gained 811,827 votes, representing 2.6% of the national total; it failed to win any seats in the House of Commons.

Following the election, psephologists argued that the impact of the Referendum Party deprived Conservative candidates of victory in somewhere between four and sixteen parliamentary seats.

[4][5] Goldsmith had once been a strong supporter of the EC but had grown disenchanted with it during the early 1990s, becoming particularly concerned that it was forming into a superstate governed by centralised institutions in Brussels.

[8] Goldsmith's intervention in British politics has been compared with that of the multi-millionaires Ross Perot in the United States and Silvio Berlusconi in Italy.

We the rabble army, we in the Referendum Party, we will strive with all our strength to obtain for the people of these islands the right to decide whether or not Britain should remain a nation."

"[10][11] The political scientists David Butler and Dennis Kavanagh noted that this question was often mocked for its "unrealistic ambiguity",[12] and some journalists referred to Goldsmith's venture as the "Referendum Only Party".

[16] To counter this problem, Goldsmith sought to create a sophisticated administrative centre and to secure the expertise to carry out a political campaign,[16] establishing his headquarters in London.

[16] The centre had around 50 staff, who relayed Goldsmith's instructions through to the ten regional co-ordinators, who in turn transmitted them to the prospective candidates in the constituencies.

[16] This top-down and undemocratic structure concentrated decision making with Goldsmith and the centre and provided little autonomy for the regions and constituencies, although this was deemed necessary to ensure efficiency in its campaign.

[20] Among the speakers were the actor Edward Fox, the ecologist David Bellamy, the politician George Thomas, and the zookeeper John Aspinall.

[21] Early supporters fell largely into three types: committed Eurosceptics, disaffected Conservatives, and those who—though not necessarily being Eurosceptic—strongly believed that the British population deserved a referendum on EU membership.

[13] Despite Goldsmith's longstanding criticism of the mainstream media—he had previously stated that "reporting in England is a load of filth"—the party used its finances to promote its message in the media.

[27][28] By the time of the 1997 general election, polls suggested that Eurosceptic sentiment was running high in the UK, and the question of the country's ongoing membership of the EU was a topic of regular discussion in the media.

[30] Such debates were influenced by the UK's recent signing of the Maastricht Treaty and the looming possibility that the country would adopt the euro currency.

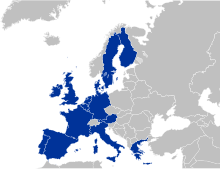

[35] In his analysis of the video, scholar David Hass argued that the film was deliberately designed to elicit fear in the viewer, something achieved through "eerie sound effects", the image of a blue stain spreading across a map of Europe, and slow-motion shots of German Chancellor Helmut Kohl striding towards the screen.

[36] In Hass' view, the film "manifestly reduced that complex issue of Europe to the lowest common denominator, and aimed to shock.

[39] Goldsmith implied that the BBC had a pro-EU agenda by referring to it as the "Brussels News Corporation", also claiming that there was a "conspiracy of silence" negatively impacting the coverage received by his party.

[42] Hurd declared that "the government's policy must not be put at the mercy of millionaires who play with British politics as a hobby or as a boost to newspaper sales".

[44] Goldsmith appeared to acknowledge that it was unlikely to win any of the contested seats, stating that the party's success would be "judged solely by its total number of votes".

[21] The party officially launched its electoral campaign on 9 April 1997 at Newlyn in Cornwall, where Goldsmith sought to whip up Eurosceptic sentiment among fishermen who were angry with the restrictions imposed by EU fishing quotas.

[57] The Referendum Party had proved more electorally successful than its Eurosceptic rival, UKIP, which averaged 1.2% of the vote in the 194 constituencies that it contested.

First, it helped promote Europe on the political agenda and added to the pressure which eventuated in the three major parties promising a referendum on the specific issue of EMU membership.

Second, although the party had no effect on the outcome of the [1997 general] election, it did attract a respectable level of support and its presence contributed to the Conservative's dismal electoral performance."

[61] As noted by Anthony Heath, Roger Jowell, Bridget Taylor, and Katarina Thomson from their analysis of polling data, "voters for the Referendum Party were certainly not a cross-section of the electorate.

[65] According to analysis by the political scientist John Curtice and psephologist Michael Steed, "only a handful of the Conservatives' losses of seats can be blamed on the intervention of the Referendum Party".

[32] On employing aggregate constituency data, Ian McAllister and Donley T. Studlar disagreed, arguing that the Referendum Party had a greater impact on the Conservatives than previous research suggested.

[65] Some of its members transformed into the Democracy Movement, a pressure group closely associated with the former Conservative supporter and multi-millionaire businessman Paul Sykes.

[69] The Eurosceptic cause was weakened; with Blair's firmly pro-EU government in power, by 1998 the possibility of a referendum on the UK's membership of the EU was considered as distant as it had been in 1995.

[74] In the 2001 general election, much of the support that had previously gone to the Referendum Party went not to UKIP but to the Conservatives, whose leader William Hague had employed Eurosceptic rhetoric throughout his campaign.