Reformation Papacy

Luther, who had spent time in Rome,[1] claimed that Pope Leo had vetoed a measure that cardinals should restrict the number of boys they kept for their pleasure, "otherwise it would have been spread throughout the world how openly and shamelessly the pope and the cardinals in Rome practice sodomy;" encouraging Germans not to spend time fighting fellow countrymen in defense of the papacy.

Pope Paul III (1534–1549) initiated the Council of Trent (1545–1563), a commission of cardinals tasked with institutional reform, to address contentious issues such as corrupt bishops and priests, indulgences, and other financial abuses.

The Council clearly rejected specific Protestant positions and upheld the basic structure of the Medieval Church, its sacramental system, religious orders, and doctrine.

Among the conditions to be corrected by Catholic reformers was the growing divide between the priests and the flock; many members of the clergy in the rural parishes, after all, had been poorly educated.

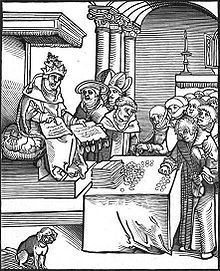

The worldly excesses of the secular Renaissance church, epitomized by the era of Alexander VI (1492–1503), exploded in the Reformation under Pope Leo X (1513–1521), whose campaign to raise funds in the German states to rebuild St. Peter's Basilica by supporting sale of indulgences was a key impetus for Martin Luther's 95 Theses.

The Council, by virtue of its actions, repudiated the pluralism of the Secular Renaissance Church: the organization of religious institutions was tightened, discipline was improved, and the parish was emphasized.

Zealous prelates such as Milan's Archbishop Carlo Borromeo (1538–1584), later canonized as a saint, set an example by visiting the remotest parishes and instilling high standards.

Paul IV is sometimes deemed the first of the Counter-Reformation popes for his resolute determination to eliminate all "heresies" - and the institutional practices of the Church that contributed to its appeal.

In this sense, his aggressive and autocratic efforts of renewal greatly reflected the strategies of earlier reform movements, especially the legalist and observantine sides: burning heretics and strict emphasis on Canon law.

While the aggressive authoritarian approach was arguably destructive of personal religious experience, a new wave of reforms and orders conveyed a strong devotional side.

The pontificate of Pope Sixtus V (1585–1590) opened up the final stage of the Catholic Reformation characteristic of the Baroque age of the early seventeenth century, shifting away from compelling to attracting.