Church of Scotland

[10] An assembly of some nobles, lairds, and burgesses, as well as several churchmen, claiming in defiance of the Queen to be a Scottish Parliament, abolished papal jurisdiction and approved the Scots Confession, but did not accept many of the principles laid out in Knox's First Book of Discipline, which argued, among other things, that all of the assets of the old church should pass to the new.

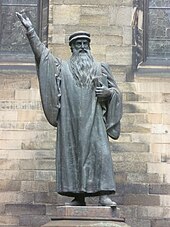

John Knox himself had no clear views on the office of bishop, preferring to see them renamed as 'superintendents' which is a translation of the Greek; but in response to the new Concordat, a Presbyterian party emerged headed by Andrew Melville, the author of the Second Book of Discipline.

[citation needed] Melville and his supporters enjoyed some temporary successes—most notably in the Golden Act of 1592, which gave parliamentary approval to Presbyterian courts.

[citation needed] Charles I inherited a settlement in Scotland based on a balanced compromise between Calvinist doctrine and episcopal practice.

Disapproving of the 'plainness' of the Scottish service, he, together with his Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, sought to introduce the kind of liturgical practice in use in England.

Although a panel of Scottish bishops devised this, Charles's insistence that it be drawn up secretly and adopted sight unseen led to widespread discontent.

When the Prayer Book was finally introduced at St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh in mid-1637, it caused an outbreak of rioting, which, starting with Jenny Geddes, spread across Scotland.

In early 1638, the National Covenant was signed by large numbers of Scots, protesting the introduction of the Prayer Book and other liturgical innovations that had not first been tested and approved by free Parliaments and General Assemblies of the Church.

In November 1638, the General Assembly in Glasgow, the first to meet for twenty years, not only declared the Prayer Book unlawful but went on to abolish the office of bishop itself.

In the ensuing civil wars, the Scots Covenanters at one point made common cause with the English parliamentarians—resulting in the Westminster Confession of Faith being agreed by both.

[12] Episcopacy was reintroduced to Scotland after the Restoration, which caused considerable discontent, especially in the country's southwest, where the Presbyterian tradition was strongest.

[citation needed] The 1929 assembly of church leaders to effect the Union of that year met at Industrial Hall on Annandale Street in north Edinburgh.

[citation needed] The motto of the Church of Scotland is nec tamen consumebatur (Latin)—"Yet it was not consumed", an allusion to Exodus 3:2 and the Burning Bush.

"[14] In 2019, the Church of Scotland paid £1 million in damages to three siblings who had been abused at the Lord and Lady Polwarth children's home.

Traditionally, Scots worship centred on the singing of metrical psalms and paraphrases, but for generations these have been supplemented with Christian music of all types.

In recent years, a variety of modern song books have been widely used to appeal more to contemporary trends in music, and elements from alternative liturgies including those of the Iona Community are incorporated in some congregations.

The present inter-denominational co-operation marks a distinct change from attitudes in certain quarters of the church in the early twentieth century and before, when opposition to Irish Roman Catholic immigration was vocal (see Catholicism in Scotland).

In His love, this living Jesus invites us to turn from our sins and enter by faith into a restored relationship with God Who gives true life before and beyond death.

[31] In a landmark decision on 23 May 2009 the General Assembly (GA) ratified by 326 to 267 the appointment of Scott Rennie, the church's first out, non-celibate gay minister.

Rennie had won the overwhelming support of his prospective church members at Queen's Cross, Aberdeen, but his appointment was in some doubt until extensive debate and this vote by the commissioners to the assembly.

[33] In May 2011, the GA of the Church of Scotland voted to appoint a theological commission with a view to fully investigating the matter, reporting to the General Assembly of 2013.

This raises an increasing number of difficulties and current Israeli policies regarding the Palestinians have sharpened this questioning", and that "promises about the Land of Israel were never intended to be taken literally".

[49] The Scottish Council of Jewish Communities sharply criticised the report,[50] describing it as follows: "It reads like an Inquisition-era polemic against Jews and Judaism.

[56] The Church of Scotland is anti-abortion, stating that it should be allowed "only on grounds that the continuance of the pregnancy would involve serious risk to the life or grave injury to the health, whether physical or mental, of the pregnant woman.

The church has frequently stressed its opposition to various attempts to introduce legislation to permit euthanasia, even under strictly controlled circumstances as incompatible with Christianity."

"[58] Historically, the Church of Scotland supported the death penalty; the General Assembly once called for the "vigorous execution" of Thomas Aikenhead, who was found guilty of blasphemy in 1696.

The minister who is asked to perform a ceremony for someone who has a prior spouse living may inquire for the purpose of ensuring that the problems which led to the divorce do not recur.

The church played a leading role in providing universal education in Scotland (the first such provision in the modern world), largely due to its teaching that all should be able to read the Bible.

The National Youth Assembly, often shortened to NYA, was an annual gathering of young people aged between 17 and 25 years old within the Church of Scotland.

The Principal Clerk to the General Assembly is Fiona Smith (the first woman to hold the post full-time), who succeeded George Whyte in 2022.