Recovered Territories

Over the centuries, however, they had become predominantly German-speaking through the processes of German eastward settlement (Ostsiedlung), political expansion (Drang nach Osten), as well as language shift due to Germanisation of the local Polish, Slavic and Baltic Prussian population.

[6] The Soviet-appointed communist authorities that conducted the resettlement also made efforts to remove many traces of German culture, such as place names and historic inscriptions on buildings.

The term "Recovered Territories" was officially used for the first time in the Decree of the President of the Republic of 11 October 1938 after the annexation of Trans-Olza by the Polish army.

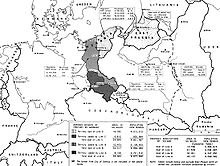

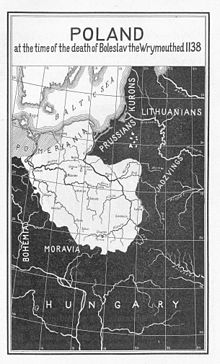

[9] The term "Recovered Territories" is a collective term for different areas with different histories, which can be grouped into three categories: The underlying concept was to define post-war Poland as heir to the medieval Piasts' realm,[10][11][12] which was simplified into a picture of an ethnically homogeneous state that matched post-war borders,[13] as opposed to the later Jagiellon Poland, which was multi-ethnic and located further east.

[15][17][19][20] Dmitrow says that "in official justifications for the border shift, the decisive argument that it presented a compensation for the loss of the eastern half of the pre-war Polish territory to the USSR, was viewed as obnoxious and concealed.

In 1962, Pope John XXIII referred to those territories as the "western lands after centuries recovered", and did not revise his statement, even under pressure of the German embassy.

His realm roughly included all of the area of what would later be named the "Recovered Territories", except for the Warmian-Masurian part of Old Prussia and eastern Lusatia.

Mieszko's son and successor, Duke Bolesław I Chrobry, upon the 1018 Peace of Bautzen expanded the southern part of the realm, but lost control over the lands of Western Pomerania on the Baltic coast.

After fragmentation, pagan revolts and a Bohemian invasion in the 1030s, Duke Casimir I the Restorer (reigned 1040–1058) again united most of the former Piast realm, including Silesia and Lubusz Land on both sides of the middle Oder River, but without Western Pomerania, which became part of the Polish state again under Bolesław III Wrymouth from 1116 until 1121, when the noble House of Griffins established the Duchy of Pomerania.

Władysław I the Elbow-high, crowned King of Poland in 1320, achieved partial reunification, although the Silesian and Masovian duchies remained independent Piast holdings.

In the course of the 12th to 14th centuries, Germanic, Dutch and Flemish settlers moved into East Central and Eastern Europe in a migration process known as the Ostsiedlung.

They built on the theory of the Corona Regni Poloniae, according to which the state (the Crown) and its interests were no longer strictly connected with the person of the monarch.

Astronomer Jan of Głogów and scholar Laurentius Corvinus, who were teachers of Nicolaus Copernicus at the University of Kraków, both hailed from Lower Silesia.

Also painters Daniel Schultz, Tadeusz Kuntze and Antoni Blank, as well as composers Grzegorz Gerwazy Gorczycki and Feliks Nowowiejski were born in these lands.

In the interwar period the German administration, even before the Nazis took power, conducted a massive campaign of renaming of thousands of placenames, to remove traces of Slavic origin.

Successful Christian missions ensued in 1124 and 1128; however, by the time of Bolesław's death in 1138, most of West Pomerania (the Griffin-ruled areas) was no longer controlled by Poland.

Indigenous Slavs and Poles faced discrimination from the arriving Germans, who on a local level since the 16th century imposed discriminatory regulations, such as bans on buying goods from Slavs/Poles or prohibiting them from becoming members of craft guilds.

After the Treaty of Kępno in 1282, and the death of the last Samboride in 1294, the region was ruled by kings of Poland for a short period, although also claimed by Brandenburg.

The Bishopric of Lebus, established by Polish Duke Bolesław III Wrymouth, remained a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Gniezno until 1424, when it passed under the jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Magdeburg.

In order to repopulate the conquered areas, Poles from neighboring Masovia, called Masurians (Mazurzy), were allowed to settle here (hence the name Masuria).

[44] Before the outbreak of war, regions of Masuria, Warmia and Upper Silesia still contained significant ethnic Polish populations, and in many areas the Poles constituted a majority of the inhabitants.

[47] However these data, concerning ethnic minorities, that came from the census conducted during the reign of the NSDAP (Nazi Party) is usually not considered by historians and demographers as trustworthy but as drastically falsified.

[12] Largely excepted from the expulsions of Germans were the "autochthons", close to three million ethnically Polish/Slavic inhabitants of Masuria (Masurs), Pomerania (Kashubians, Slovincians) and Upper Silesia (Silesians).

[12] According to Norman Davies, the young post-war generation received education informing them that the boundaries of the People's Republic were the same as those on which the Polish nation had developed for centuries.

[72] Historian John Kulczycki argues that the Communist authorities discovered that forging an ethnically homogeneous Poland in the Recovered Territories was quite complicated, for it was difficult to differentiate German speakers who were "really" Polish and those who were not.

Their decisions were based on the nationalist assumption that an individual's national identity is a lifetime "ascriptive" characteristic acquired at birth and not easily changed.

[80] People from all over Poland quickly moved in to replace the former German population in a process parallel to the expulsions, with the first settlers arriving in March 1945.

[47] The settlers can be grouped according to their background: Polish and Soviet newspapers and officials encouraged Poles to relocate to the west – "the land of opportunity".

[83] These new territories were described as a place where opulent villas abandoned by fleeing Germans waited for the brave; fully furnished houses and businesses were available for the taking.

5,000 lorries are available to bring settlers to the west.During the Cold War the official position in the First World was that the concluding document of the Potsdam Conference was not an international treaty, but a mere memorandum.