Regents of the University of California v. Bakke

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978), was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that involved a dispute over whether preferential treatment for minorities could reduce educational opportunities for whites without violating the Constitution.

However, the court ruled that specific racial quotas, such as the 16 out of 100 seats set aside for minority students by the University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, were impermissible.

Proponents deemed such programs necessary to make up for past discrimination, while opponents believed they violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Finding diversity in the classroom to be a compelling state interest, Powell opined that affirmative action in general was allowed under the Constitution and the Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

[1] Among other progressive legislation, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964,[2] Title VI of which forbids racial discrimination in any program or activity receiving federal funding.

[10][11] The application form contained a question asking if the student wished to be considered disadvantaged, and, if so, these candidates were screened by a special committee, on which more than half the members were from minority groups.

Bakke attended the University of Minnesota for his undergraduate studies, deferring tuition costs by joining the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps.

In order to fulfill his ROTC requirements, he joined the Marine Corps and served four years, including a seven-month tour of duty in Vietnam as a commanding officer of an anti-aircraft battery.

[35] According to a 1976 Los Angeles Times article, the dean of the medical school sometimes intervened on behalf of daughters and sons of the university's "special friends" in order to improve their chances.

[37] On June 20, 1974,[38] following his second rejection from UC Davis, Bakke brought suit against the university's governing board in the Superior Court of California,[33] Yolo County.

He sought an order admitting him on the ground that the special admission programs for minorities violated the U.S. and California constitutions, and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

UC Davis's counsel filed a request that the judge, F. Leslie Manker, find that the special program was constitutional and legal, and argued that Bakke would not have been admitted even if there had been no seats set aside for minorities.

[38][50][51] The university requested that the U.S. Supreme Court stay the order requiring Bakke's admission pending its filing of a petition asking for a review.

A number of civil rights organizations filed a joint brief as amicus curiae, urging the court to deny review, on the grounds that the Bakke trial had failed to develop the issues fully as the university had not introduced evidence of past discrimination or of bias in the MCAT.

Cox wrote much of the brief, and contended in it that "the outcome of this controversy will decide for future generations whether blacks, Chicanos, and other insular minorities are to have meaningful access to higher education and real opportunities to enter the learned professions".

[57] Reynold Colvin, for Bakke, argued that his client's rights under the Fourteenth Amendment to equal protection of the laws had been violated by the special admission program.

[58] Fifty-eight amicus curiae briefs were filed, establishing a record for the Supreme Court that would stand until broken in the 1989 abortion case Webster v. Reproductive Health Services.

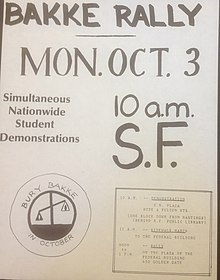

That document, filed October 3, 1977 (nine days before the oral argument), stated that the government supported programs tailored to make up for past discrimination, but opposed rigid set-asides.

[60] The United States urged the court to remand the case to allow for further fact-finding (a position also taken by civil rights groups in their amicus curiae briefs).

[60] While the case was awaiting argument, another white student, Rita Clancy, sued for admission to UC Davis Medical School on the same grounds as Bakke had.

[66] The supplemental brief for the university was filed on November 16, and argued that Title VI was a statutory version of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and did not allow private plaintiffs, such as Bakke, to pursue a claim under it.

[68] On November 22, Justice Lewis Powell submitted a memo that analyzed the university's minority admissions program under the strict scrutiny standard which is often applied when the government treats some citizens differently based on a suspect classification such as race.

The other four justices (Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun) dissented from that portion of the decision, but joined with Powell to find affirmative action permissible under some circumstances, though subject to an intermediate scrutiny standard of analysis.

The Washington Post, a liberal newspaper, began its headline in larger-than-normal type, "Affirmative Action Upheld" before going on to note that the court had admitted Bakke and curbed quotas.

[95] According to Oxford University Chair of Jurisprudence Ronald Dworkin, the court's decision "was received by the press and much of the public with great relief, as an act of judicial statesmanship that gave to each party in the national debate what it seemed to want most".

[97] Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Chair Eleanor Holmes Norton told the media "that the Bakke case has not left me with any duty to instruct the EEOC staff to do anything different".

[100] Law professor and future judge Robert Bork wrote in the pages of The Wall Street Journal that the justices who had voted to uphold affirmative action were "hard-core racists of reverse discrimination".

The large majority of affirmative action programs at universities, unlike that of the UC Davis medical school, did not use rigid numerical quotas for minority admissions and could continue.

[102] According to Bernard Schwartz in his account of Bakke, the Supreme Court's decision "permits admission officers to operate programs which grant racial preferences—provided that they do not do so as blatantly as was done under the sixteen-seat 'quota' provided at Davis".

[110] Dworkin warned in 1978 that "Powell's opinion suffers from fundamental weaknesses, and if the Court is to arrive at a coherent position, far more judicial work remains to be done than a relieved public yet realizes".