Vernacular architecture

It is not a particular architectural movement or style, but rather a broad category, encompassing a wide range and variety of building types, with differing methods of construction, from around the world, both historical and extant and classical and modern.

The study of vernacular architecture does not examine formally schooled architects, but instead that of the design skills and tradition of local builders, who were rarely given any attribution for the work.

In this "vernacular" category Scott included St Paul's Cathedral, Greenwich Hospital, London, and Castle Howard, although admitting their relative nobility.

The term was popularized with positive connotations in a 1964 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, designed by architect Bernard Rudofsky, with a subsequent book.

"[16] The book was a reminder of the legitimacy and "hard-won knowledge" inherent in vernacular buildings, from Polish salt-caves to gigantic Syrian water wheels to Moroccan desert fortresses and was considered iconoclastic at the time.

[17]In the Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World edited in 1997 by Paul Oliver of the Oxford Institute for Sustainable Development.

All forms of vernacular architecture are built to meet specific needs, accommodating the values, economies and ways of life of the cultures that produce them.

[18]In 2007 Allen Noble wrote a lengthy discussion of the relevant terms, in Traditional Buildings: A Global Survey of Structural Forms and Cultural Functions.

"Vernacular architecture" is "of the common people", but may be built by trained professionals, using local, traditional designs and materials.

Paul Oliver, in his book Dwellings, states: "it is contended that 'popular architecture' designed by professional architects or commercial builders for popular use, does not come within the compass of the vernacular".

[21]: 9 suggesting that it is a primitive form of design, lacking intelligent thought, but he also stated that it was "for us better worth study than all the highly self-conscious academic attempts at the beautiful throughout Europe".

The Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck was also a proponent of vernacular architecture,[21] as were Samuel Mockbee, Christopher Alexander, and Paolo Soleri.

Oliver claims that: As yet there is no clearly defined and specialized discipline for the study of dwellings or the larger compass of vernacular architecture.

[21][clarification needed]Architects have developed a renewed interest in vernacular architecture as a model for sustainable design.

In hot arid and semi-arid regions, vernacular structures typically include a number of distinctive elements to provide for ventilation and temperature control.

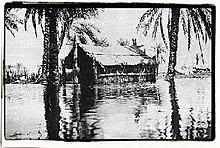

For example, the Queenslander is an elevated weatherboard house with a sloped, tin roof that evolved in the early 19th-century as a solution to the annual flooding caused by monsoonal rain in Australia's northern states.

Similarly, Northern African vernacular often has very high thermal mass and small windows to keep the occupants cool, and in many cases also includes chimneys, not for fires but to draw air through the internal spaces.

Such specializations are not designed but learned by trial and error over generations of building construction, often existing long before the scientific theories which explain why they work.

The Sami of Northern Europe, who live in climates similar to those experienced by the Inuit, have developed different shelters appropriate to their culture[21]: 25 including the lavvu and goahti.

A ger is typically not often relocated, and is therefore sturdy and secure, including wooden front door and several layers of coverings.

A traditional Berber tent, by contrast, might be relocated daily, and is much lighter and quicker to erect and dismantle – and because of the climate it is used in, does not need to provide the same degree of protection from the elements.

In some cases, however, where dwellings are subjected to severe weather conditions such as frequent flooding or high winds, buildings may be deliberately "designed" to fail and be replaced, rather than requiring the uneconomical or even impossible structures needed to withstand them.

A case that made news in Russia was that of an Arkhangelsk entrepreneur Nikolay P. Sutyagin, who built what was reportedly the world's tallest single-family wooden house for himself and his family, only to see it condemned as a fire hazard.