Reign of Alfonso XII

[19] At the end of February 1870 the prince traveled to Rome to receive the first communion from Pius IX, but without achieving, as the ex-Queen intended, that the pope publicly recognize the Bourbon dynasty as the legitimate depositary of the rights to the Spanish throne and that he condemn the "revolutionary regime" established in Spain.

[58] What was to be a decisive step in the Alfonsine restoration took place on August 22, 1873 ―in the midst of the cantonal rebellion after the proclamation of the Federal Republic and only one month after the pretender Carlos VII had returned to Spain, thus giving a great impulse to the third Carlist war― when Isabella II gave her full support to Cánovas, in spite of her antipathy towards him,[59] and entrusted him with the direction of the Bourbon dynastic cause.

[74] Manuel Suárez Cortina has pointed out that "the identification between revolution and democracy, the fear radiated by the Parisian Commune and the decisive fact that the Sexenio had not substantially altered the foundations of power had stimulated the reorganization of the sectors most inclined to liquidate the democratic experience.

[96][97][98][99] Formally, it was a letter sent from the British Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, where Prince Alfonso had entered at the beginning of October at the initiative of Cánovas with the aim of enhancing his constitutional image,[100][101][102] in response to the numerous congratulations he had received from Spain on the occasion of his 17th birthday.

No one like Your Excellency, to whom I owe and thank so much for your relevant services, as well as the Regency Ministry that you have appointed, using the powers that I conferred on you and today confirm, can interpret my feelings of gratitude and love for the nation, ratifying the opinions consigned in the manifesto of December 1st last and affirming my loyalty to fulfill them and my very lively desires that the solemn act of my entrance into my beloved homeland be a pledge of peace, of union and of forgetting the past discords, and, as a consequence of all this, the inauguration of a true freedom and that adding our efforts and with the protection of heaven, we can reach for Spain new days of prosperity and greatness.

In Peralta (Navarra) he appealed to the Carlists in favor of peace ("Before unfurling my flag in battle, I want to present myself to you with an olive branch in my hand"), but he also assured them that he was not going to "tolerate even a useless war like the one you wage against the rest of the nation" and "that they had no reason to continue it" ("if you took up arms moved by the monarchic faith, see in me the legitimate representative of a dynasty that was loyal to you until its passing fall.

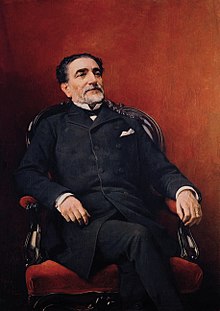

[163] The fundamental objective of the political project of Antonio Cánovas del Castillo ―who prided himself on "paying due tribute to prudence, to the spirit of compromise, to the law of reality"―[164] was to achieve, at last, the consolidation and stability of the liberal State, on the basis of the Constitutional Monarchy defined in the Sandhurst Manifesto.

[166] In order to implement his political project, Cánovas had the absolute confidence of King Alfonso XII, who in a conversation with the British ambassador Austen Henry Layard had expressed his desire to "introduce in Spain the constitutional system to which England owed its liberties and greatness".

[164][171][172][173] Although the ultimate goal pursued by Cánovas was to divide them and attract them to his project,[174][175][176] at the beginning he made concessions to the moderates and the first measures agreed by the new government meant a revision of what had been done during the Sexenio, besides building a very negative image of the period and especially of the first year of the First Spanish Republic, described by the traditionalist Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo as "times of apocalyptic desolation".

[164][194][195][196] In the circular that accompanied the decree addressed to the rectors of the universities and signed by Minister Orovio, the latter were invited "not to consent that in the chairs supported by the State they should explain against the Catholic dogma that is the social truth in our country" and it was also warned that any professor who "did not recognize the established regime or taught against it" would be sanctioned.

With the same purpose ―"to give confidence to the moderate sectors and neutralize any attempt to put an end to the regime"― he also "sought the reestablishment of relations with the Vatican, restored the budget for worship and clergy [the economic endowment that the State gave to the Catholic Church] and reintroduced the obligatory nature of canonical marriage".

[200] According to Carlos Seco Serrano, Orovio's presence in the government ―and his controversial decree― was due to "the fact that the civil war had not yet been defeated, demanded, in any case, the adoption of political measures that could suppose a more or less homologous "gesture" with the monarchic and religious concept that animated the Carlist camp ―in order to disarm it ideologically"―.

[226][227] The king supported it without fail, in spite of the "systematic siege" to which he was subjected "by Moderate politicians, a large part of the nobility and high clergy, and even by the princess of Asturias, favorable de cuore, in the opinion of the pontifical representative, to the Catholic cause".

As for ex-Queen Isabella II, unwilling "to play decorative roles",[230] Cánovas sent her a letter to Paris in April 1875 explaining why she should not come to Spain:[231][232]Whoever comes to Madrid, the opinion will remain calm, unless you, V.M., that then a dozen illusions, moved by particular interests, will think to see in you, Your Majesty, a banner of grievances and perhaps of revenge, that will satisfy their evil passions; others will fear the beginning of a reaction that will remove from power all those who have more or less figured in the last six years and, before they are thrown out, they will voluntarily leave, creating a vacuum around the Throne... And all because you, Your Majesty, are not a person, but a reign, a historical epoch, and what the country needs today is another reign and another epoch, different from the previous ones.Not only Cánovas, but also his own son urged him not to travel to Spain, alleging that "no one can impose his will on the King".

[316] As José María Jover has pointed out, "any historical analysis of the Constitution of 1876 must start from the fact that the political dynamics foreseen in its articles ―the decisive role of the electoral body, of the parliamentary majorities that theoretically share with the king the function of maintaining or overthrowing governments― not only is it not going to develop in practice in accordance with such formal provisions, but its very architects count beforehand on this mismatch between the letter and the reality of its application".

[317] Based on this duality "formal constitution and real functioning of political life",[318] "the parties could [from power] develop their projects at the same time that they had the budget and jobs in the administration to satisfy their clientele; that is, to grant favors to their followers, who could share common ideas, but also sought material benefits", asserted Carlos Dardé.

[322] On the military level, the first operation, commanded personally by the Minister of War, General Jovellar, was directed against the so-called Carlist "center" zone, which included territories of Aragon, the extreme south of Catalonia, the north of Valencia and Castile, where guerrilla groups were active.

[358] In the instructions, disagreed by the less conservative ministers of the government such as Manuel Alonso Martínez or José Luis Albareda and also by the foreign ambassadors, particularly the British one, it was stated:[359] It is a public manifestation (and therefore constitutionally subject to prohibition) any act executed in the street or on the exterior walls of the temple or cemetery that makes known ceremonies, rites, uses and customs of the dissident cult.

[390][391][392][393] Sagasta's constitutionalists protested because they were not called to govern, but, according to Carlos Dardé, "it seems clear that this party was still too weak and, above all, that some important military elements of it, such as General Serrano, Duke de la Torre, had not yet fully accepted the new monarchy and were involved in republican projects".

[391][412] The slaveholders succeeded in getting the law's implementing regulations to introduce even greater restrictions, such as the application of the punishment of "stocks and shackles" to "sponsored slaves" who refused to work, left the plantation without authorization, promoted strikes or disobeyed the orders of the overseers.

[441] On January 19, 1881, in the midst of an intense parliamentary debate, Sagasta claimed from the "royal prerogative" his right to govern, warning that without his concurrence the Alphonsine Monarchy would not be consolidated and launching a veiled threat:[442][443][444]If my efforts and my sacrifices were sterile because of your obstinacy and your tenacity, I will see it with a sorrowful soul, but with a clear conscience; because whatever the vicissitudes, whatever the destiny we all have prepared, as I must always fall on the side of freedom, I will then say with my forehead raised: I am where I was; neither then did I obey the inspirations of patriotism, nor today do I yield to the impulses of duty and the feelings of the heart.Shortly afterwards, the king received the highest party officials at the Palace on the occasion of his birthday (January 23) and finally forced the resignation of Cánovas on February 6 when he refused to sign a decree that he presented to him, and then entrusted the formation of a government to Sagasta.

[452][465] Sagasta had to maintain the balance between all of them,[452][465] also taking into account that the liberals, like the conservatives, "were organized, like any party "of notables" of the time, in dense clientelist networks that spread from Madrid throughout the peninsular geography and whose loyalty depended, more than on great ideological programs or personal friendships, on their ability to dispense all kinds of favors to their co-religionists that presupposed the discretionary, arbitrary and, therefore, fraudulent use of the administrative mechanisms".

Among the former, the provincial organic law, which established an electoral census close to universal suffrage ―on the other hand, the bills on local administration, right of association, contentious-administrative jurisdiction and trial by jury were not debated in the Cortes― and among the latter, the trade treaty with France in February 1882, which aimed to open the French market to Spanish wines in exchange for tariff concessions to French industrial products, which was contested by the protectionist sectors, especially in Catalonia,[481] and the reform of the Treasury, carried out by the Minister of Finance Juan Francisco Camacho de Alcorta ―which included a law on the conversion of the public debt, which with notable success allowed to lighten the burden of this in the budgets and to recover the credit in the international markets―, although the changes in the fiscal field were minimal (the consumption tax, falling on the popular classes, continued to be the most important after the customs tax).

[497] In fact, General Martínez Campos refused to be relieved at the head of the Ministry of War and also demanded that Vega de Armijo continue as Minister of State —he was to be replaced by the Marquis of Sardoal, another politician who like Romero Girón came from the Dynastic Left— and Sagasta had no choice but to compromise.

[567] Pidal y Mon had stood out during the debate on the Constitution of 1876 for his fierce defense of Catholic unity, but in 1880 he had accepted the legality in force and made a resounding appeal to "the honest masses who, thrown into the countryside by the excesses of the revolution, formed the Carlist party" to join the conservative camp.

[567][572][573] On April 27, 1884 ―that day the serious railway accident known as the catastrophe of the Alcudia Bridge in which 53 people died took place―[574] elections were held, again by census suffrage, which predictably gave a large majority to the Liberal-Conservative Party (318 deputies) due to the "good work" of Romero Robledo from the Ministry of the Interior.

[563][604] Despite the fact that his state of health was worsening ―"as a courageous man, he resists well and hides the progress of the ailment from the Queen and the doctors, but he loses strength every day", commented Cánovas del Castillo privately―, the king made an incognito trip to Aranjuez to visit the local cholera patients, which caused a constitutional crisis, since he did so against the express prohibition of the government.

Since I stood up to propose concord and to ask for a truce, there was no other way to make people believe my sincerity but to remove myself from power.As Ramón Villares has pointed out, "the death of King Alfonso XII and the agreement or pact of 1885 (improperly called the Pacto del Pardo) definitively marked the consolidation of the regime" of the Restoration.

[622] A good part of the Catholic ecclesiastical hierarchy, with the nuncio Rampolla at the head, also played an important role in the consolidation of the regime by making public on December 14, 1855, a declaration of support for the Regency, applying the principles of the encyclical Immortale Dei on the relations between Church and State that Pope Leo XIII had just published.

[627][628] As for the Carlists, the pretender Carlos VII, in exile after his defeat in the war like many other leaders, decided in 1878 to abandon the insurrectionary path and named Cándido Nocedal his representative in Spain ―his press organ would be El Siglo Futuro―, who imposed the identification between Carlism and Catholicism.