Regency of Maria Christina of Austria

In the domestic sphere, the Spanish society underwent a considerable mutation, with the appearance of such significant political realities as the emergence of regionalisms and peripheral nationalisms, the strengthening of a workers' movement of double affiliation, socialist and anarchist, and the sustained persistence, although decreasing, of the republican and Carlist oppositions".

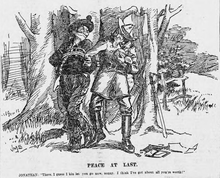

Since I stood up to propose concord and to ask for a truce, there was no other way to make people believe in my sincerity but to remove myself from power.In June, the various liberal factions had reached an agreement, known as the law of guarantees, which made it possible to reestablish the unity of the party.

An extremely delicate task, since the situation of hypertrophy, the excess of officers, the poor equipment and the esprit de corps, based on a strong tradition of self-recruitment, had made the Armed Forces a reality that was not very permeable to external demands and controls".

Although the anarchist movement continued to be present through publications and educational initiatives, the dissolution of the FTRE opened "the way for the predominance of individual actions of a terrorist nature, for the propaganda of the deed that it would proliferate in the following decade".

[22] Together with the limited process of industrialization in Spain, the slow growth of workers' organizations was due to the fact that republicanism continued to constitute a basic framework of political reference for the working and popular sectors.

[23] From the Catholic world an attempt was made to create a workers' movement with this confessional significance as a result of the publication in 1891 of the papal encyclical "Rerum novarum" which encouraged initiatives in the social field.

Likewise, during this period, the process of construction of the Spanish nation continued, but from its most conservative version, as the idea of Spain did not focus on the free will of its citizens —the political nation— but on its "being", linked to its historical legacy —with Catholicism and the Castilian language as its main elements—.

From then on, opposition to the centralist State was no longer exclusive to Carlists and federalists, but was now also professed by those who felt they belonged to different homelands, especially in Catalonia, the Basque Country and Galicia, which for the time being were called regions, or at best, nationalities.

"A good part of the press, in Madrid and in the provinces, began to view with suspicion, if not with open hostility, even the regionalist cultural activities and their requests to co-officialize the non-Spanish languages, a claim that more than one accused of "covert separatism".

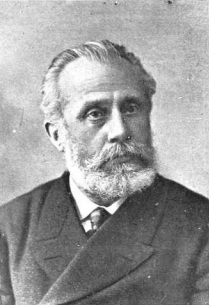

[30] In 1886, Almirall published his fundamental work Lo catalanisme, in which he defended Catalan "particularism" and the need to recognize "the personalities of the different regions into which history, geography and the character of the inhabitants have divided the peninsula".

[31] In 1887 the Centre Català experienced a crisis as a result of the rupture between the two currents that were part of it, one more leftist and federalist led by Almirall, and the other more Catalanist and conservative, grouped around the newspaper La Renaixença, founded in 1881.

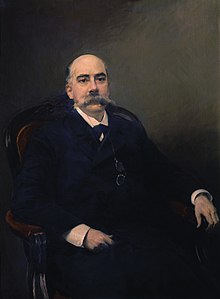

[45] Once his program of reforms was completed with the approval of universal (male) suffrage, Sagasta succeeded Cánovas del Castillo, who formed the government in July 1890, only a few days after the law had been voted in the Parliament.

[47] For this reason it was the government of Cánovas who presided over the first elections by universal suffrage held in February 1891, in which the machinery of fraud was once again at work and the conservatives obtained a large majority in the Congress of Deputies (253 seats, compared to 74 for the liberals, and 31 for the republicans).

Structured in seventeen articles, they advocate the possibility of modernizing civil law, the exclusive officialdom of Catalan, the reservation for natives of public offices, including military posts, the comarca as a basic administrative entity, exclusive internal sovereignty, corporately elected courts, a higher court of last appeal, the extension of municipal powers, voluntary military service, a body of public order and its own currency, and an education sensitive to the Catalan specificity".

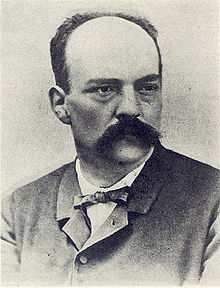

In it he explained that the political objective of the book Bizcaya por su independencia was to awaken the national conscience of the Biscayans, since Spain was not their homeland but Biscay, and he adopted the slogan Jaun-Goikua eta Lagi-Zarra (JEL, 'God and Old Law'), synthesis of his nationalist program.

The former embodied "the dominance of clientelistic practices, electoral manipulation and the triumph of the crudest pragmatism", while the latter represented "conservative reformism", which sought to "reestablish the prestige of the law and cut off all abuse, all infringement".

President Cánovas del Castillo leaned towards Romero Robledo's "pragmatism" in the face of the new situation created by the introduction of universal suffrage, so Silvela left the government in November 1891[48] and his departure provoked the greatest internal crisis in the history of the Conservative Party.

Gamazo, at the head of the Treasury portfolio, proposed to achieve a balanced budget, but his project was frustrated by the increase in spending caused by the brief Margallo war that took place around Melilla between October 1893 and April 1894.

The author of the attack, the young anarchist Paulino Pallás —who was shot two weeks later— justified it as a reprisal for the incidents that had occurred a year and a half earlier in Jerez de la Frontera when, on the night of January 8, 1892, some 500 peasants tried to take the city to free some fellow prisoners in jail and two neighbors and one of the assailants died, The indiscriminate repression of the Andalusian workers' organizations began – four workers were executed because of a court martial, and sixteen more were condemned to life imprisonment; all of them had denounced that their confessions had been obtained through torture.

The revenge announced by Paulino Pallás shortly before being shot was fulfilled three weeks later, when on November 7 the anarchist Santiago Salvador threw two bombs into the stalls of the Liceu Theater in Barcelona, although only one exploded, killing 22 people and wounding 35 others.

[64] But at the internal level anarchist terrorism also played an important role, whose attack of greater repercussion took place in Barcelona on June 7, 1896, during the passage of the Corpus Christi procession through Canvis Nous street in which six people died on the spot, and forty-two others were wounded.

[66] The Montjuic trial had great international repercussions, given the doubts about the evidence on which the convictions had been based —basically the confessions of the defendants obtained under torture—, which was also followed by a campaign by the Spanish press against the government and the "executioners", in which the young journalist Alejandro Lerroux, director of the Madrid Republican newspaper El País, stood out.

This policy of Spanishization, which was intended to counteract Cuban secessionist nationalism, was reinforced by the facilities granted for the emigration of peninsulars to the island, which was especially taken advantage of by Galicians and Asturians —between 1868 and 1894 nearly half a million people arrived, for a total population of 1,500,000 in 1868—.

[71] In the last Sunday of February 1895, the day the carnival began, a new pro-independence insurrection broke out in Cuba, planned and directed by the Cuban Revolutionary Party, founded by José Martí in New York in 1892, who would die the following month in a confrontation with Spanish troops.

[79] Relations between the U.S. and Spain worsened when the American press published a private letter from Spanish Ambassador Enrique Dupuy de Lome to Minister José Canalejas, intercepted by Cuban espionage, in which he called President McKinley "weak and populist, and also a politician who wants... to look good with the jingoes of his party".

[89] After the defeat, the Spanish nationalist patriotic exaltation gave way to a feeling of frustration, increased when the total number of dead during the war was known: about 56,000 —2,150 soldiers and officers killed in combat, and 53,500, due to various diseases—.

The historian Melchor Fernandez Almagro, who was a child when the war ended, referred to the wounded and mutilated soldiers returning from the colonial campaign "walking the streets and squares in painful and inevitable display of the uniform of rayadillo reduced to rags, with gloomy profusion of crutches, arms in sling and patches on the emaciated face".

[95] The only important opposition movement that Silvela's conservative government had to face was the taxpayers' strike —or "tancament de caixes", literally 'closing of cashboxes', in Catalonia— promoted between April and July 1900 by the National League of Producers, an organization created by the regenerationist Joaquín Costa, and by the Chambers of Commerce, led by Basilio Paraíso.

[95] The internal disagreements —mainly the result of General Polavieja's opposition to the reduction of public spending proposed by Fernández Villaverde to achieve a balanced budget, since it clashed with his request for greater economic allocations to modernize the Army— were what ended up causing the fall of Silvela's government in October 1900.

This arose from the merger of the Regionalist Union founded in 1898 and the Centre Nacional Català, which brought together a splinter group of the Unió Catalanista led by Enric Prat de la Riba and Francesc Cambó.