Religion in the Czech Republic

[1] According to sociologist Jan Spousta, not all the irreligious people are atheists; indeed, since the late 20th century there has been an increasing distancing from both Christian dogmatism and atheism, and at the same time ideas and non-institutional models similar to those of Eastern religions have become widespread through movements started by various gurus, and hermetic and mystical paths.

[3] The Christianisation of the Czechs (Bohemians, Moravians and Silesians) occurred in the 9th and 10th centuries, when they were incorporated into the Catholic Church and abandoned indigenous Slavic paganism.

[6] The Catholic Church lost about half of its adherents during the Marxist-Leninist period of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (1960–1990), and has continued to decline in the contemporary epoch after the Velvet Revolution of 1989 restored liberal democracy in Czechoslovakia.

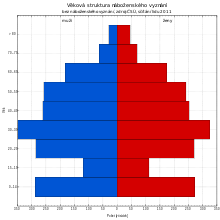

[10] Spousta also found that Christians in the early 21st century tended to be older and less educated than the general population, and females were far more likely than males to be believers.

[4] By the time of the collapse of the Habsburg power and the establishment of independent Czechoslovakia in 1918, the position of the Catholic Church had already been weakened by criticism from the intellectual class and by the social changes brought by the rapid industrialisation of especially the northern and western pars of the country, Bohemia.

[4] From 1950 onwards, Marxist-Leninists gained power in Czechoslovakia, which from 1960 to 1989 became the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, and while they fought all religions, Catholicism was targeted with particular aggressiveness.

[6] After the Velvet Revolution in 1989 and the restoration of liberal democracy in the Czech lands, Catholicism, like other forms of Christianity, did not recover and continued to lose adherents.

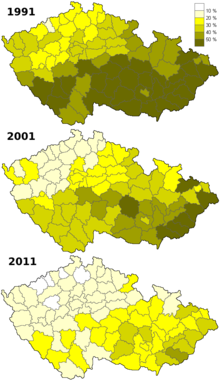

[6] The data from the national censuses show that Catholics decreased from 76.7% of the Czechs in 1950 prior to the Marxist-Leninist period, to 39.1% in 1991 after the fall of Marxism-Leninism, to 26.9% in 2001, to 10.5% in 2011, and to 9.3% in 2021.

The Defenestration of Prague and the subsequent revolt against the Habsburgs in 1618 marked the start of the Thirty Years' War, which quickly spread throughout Central Europe.

The war had a devastating effect on the local population, and the people were forced to convert back to Catholicism under the Habsburgs' Counter-Reformation efforts.

[4] In 1918, when the Habsburg monarchy disintegrated and independent Czechoslovakia emerged, most of the Czechs professed formal affiliation to Catholicism; anti-Catholic sentiments spread quickly as Catholicism was viewed as the religion re-imposed by the Habsburg, so that in 1920 the Czechoslovak Hussite Church split off the Catholic Church and was joined by about 10% of the former Catholic clergy,[4] and 10.6% of the Czechs had become again Hussites by 1950.

[21] While the contemporary association is completely adogmatic and apolitical,[22] and refuses to "introduce a solid religious or organisational order" because of the past internal conflicts,[23] between 2000 and 2010 it had a complex structure,[22] and redacted a Code of Native Faith defining a precise doctrine for Czech Rodnovery (which firmly rejected the Book of Veles).

[24] Though Rodná Víra no longer maintains structured territorial groups, it is supported by individual adherents scattered throughout the Czech Republic.

[29] Not all irreligious Czechs are atheists; a number of non-religious people believe or practise unorganised forms of spirituality which do not require strict adherence or identification, similar to Eastern religions.