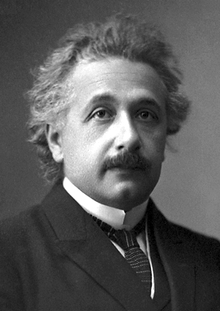

Religious and philosophical views of Albert Einstein

Out yonder there was this huge world, which exists independently of us human beings and which stands before us like a great, eternal riddle, at least partially accessible to our inspection and thinking.

"[17] Prompted by his colleague L. E. J. Brouwer, Einstein read the philosopher Eric Gutkind's book Choose Life,[18] a discussion of the relationship between Jewish revelation and the modern world.

On January 3, 1954, Einstein sent the following reply to Gutkind: "The word God is for me nothing more than the expression and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of honourable, but still primitive legends which are nevertheless pretty childish.

"[27] He expanded on this in answers he gave to the Japanese magazine Kaizō in 1923: Scientific research can reduce superstition by encouraging people to think and view things in terms of cause and effect.

You may call me an agnostic, but I do not share the crusading spirit of the professional atheist whose fervor is mostly due to a painful act of liberation from the fetters of religious indoctrination received in youth.

"[33] Einstein, in a one-and-a-half-page hand-written German-language letter to philosopher Eric Gutkind, dated Princeton, New Jersey, 3 January 1954, a year and three and a half months before his death, wrote: "The word God is for me nothing but the expression and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of venerable but still rather primitive legends.

"[34][35][36] On 17 July 1953 a woman who was a licensed Baptist pastor sent Einstein a letter asking if he had felt assured about attaining everlasting life with the Creator.

Einstein replied, "I do not believe in immortality of the individual, and I consider ethics to be an exclusively human concern with no superhuman authority behind it.

Enough for me the mystery of the eternity of life, and the inkling of the marvellous structure of reality, together with the single-hearted endeavour to comprehend a portion, be it ever so tiny, of the reason that manifests itself in nature.

In a 1915 letter to the Swiss physicist Edgar Meyer, Einstein wrote, "I see only with deep regret that God punishes so many of His children for their numerous stupidities, for which only He Himself can be held responsible; in my opinion, only His nonexistence could excuse Him.

Einstein stated, "The man who is thoroughly convinced of the universal operation of the law of causation cannot for a moment entertain the idea of a being who interferes in the course of events — that is, if he takes the hypothesis of causality really seriously.

[41] He maintained, "even though the realms of religion and science in themselves are clearly marked off from each other" there are "strong reciprocal relationships and dependencies" as aspirations for truth derive from the religious sphere.

He continued: A person who is religiously enlightened appears to me to be one who has, to the best of his ability, liberated himself from the fetters of his selfish desires and is preoccupied with thoughts, feelings and aspirations to which he clings because of their super-personal value.

In this sense religion is the age-old endeavor of mankind to become clearly and completely conscious of these values and goals and constantly to strengthen and extend their effect.

Einstein replied in the most elementary way he could: Scientific research is based on the idea that everything that takes place is determined by laws of nature, and therefore this holds for the actions of people.

To know that what is impenetrable to us really exists, manifesting itself as the highest wisdom and the most radiant beauty, which our dull faculties can comprehend only in their most primitive forms—this knowledge, this feeling, is at the center of true religiousness.

"[40] In December 1952, he commented on what inspires his religiosity, "My feeling is religious insofar as I am imbued with the insufficiency of the human mind to understand more deeply the harmony of the universe which we try to formulate as 'laws of nature.

[10] The belief system recognized a "miraculous order which manifests itself in all of nature as well as in the world of ideas," devoid of a personal God who rewards and punishes individuals based on their behavior.

"[54] In his 1934 book The World as I See It he expressed his belief that "if one purges the Judaism of the Prophets and Christianity as Jesus Christ taught it of all subsequent additions, especially those of the priests, one is left with a teaching which is capable of curing all the social ills of humanity.

[65] An investigation of the quotation by mathematician William C. Waterhouse and Barbara Wolff of the Einstein Archives in Jerusalem found that the statement was mentioned in an unpublished letter from 1947.

"[66] In 2008 the Antiques Roadshow television program aired a manuscript expert, Catherine Williamson, authenticating a 1943 letter from Einstein in which he confirms that he "made a statement which corresponds approximately" to Time magazine's quotation of him.

"[74] When the convert mentioned that family members had been gassed by the Nazis, Einstein replied that "he also felt guilty—adding that the whole Church, beginning with the Vatican, should feel guilt."

For that reason, he refused the chance aspect of quantum theory, famously telling Niels Bohr: "God does not play dice with the universe.

"[81] In letters sent to physicist Max Born, Einstein revealed his belief in causal relationships: You believe in a God who plays dice, and I in complete law and order in a world which objectively exists, and which I in a wildly speculative way, am trying to capture.

Even the great initial success of the quantum theory does not make me believe in the fundamental dice game, although I am well aware that some of our younger colleagues interpret this as a consequence of senility.

[95] Einstein maintained that people validly use certain ideas and values, such as intuition or religious faith, which cannot be proven with direct observation or logic.

"[79] In a letter to Moritz Schlick Einstein remarked that he had read Hume's book An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding "with eagerness and admiration shortly before finding relativity theory" and that "very possibly, I wouldn't have come to the solution without those philosophical studies".

In 1949, Einstein said that he "did not grow up in the Kantian tradition, but came to understand the truly valuable which is to be found in his doctrine, alongside of errors which today are quite obvious, only quite late.

"[79] Einstein explained the significance of Kant's philosophy as follows: Hume saw that concepts which we must regard as essential, such as, for example, causal connection, cannot be gained from material given to us by the senses.

Then Kant took the stage with an idea which, though certainly untenable in the form in which he put it, signified a step towards the solution of Hume's dilemma: if we have definitely assured knowledge, it must be grounded in reason itself.