Rembrandt

Yet his etchings and paintings were popular throughout his lifetime, his reputation as an artist remained high,[4] and for twenty years he taught many important Dutch painters.

Religion is a central theme in Rembrandt's works and the religiously fraught period in which he lived makes his faith a matter of interest.

[26][18] After Saskia's illness, the widow Geertje Dircx was hired as Titus' caretaker and dry nurse; at some time, she also became Rembrandt's lover.

[39] This tumultuous period deeply impacted the art industry, prompting Rembrandt to seek a high court arrangement known as cessio bonorum.

[43] In November 1657 another auction was held to sell his paintings, as well as a substantial number of etching plates and drawings, some by renowned artists such as Raphael, Mantegna and Giorgione.

The sale list comprising 363 items offers insight into Rembrandt's diverse collections, which, encompassed Old Master paintings, drawings, Roman emperors busts, Greek philosophers statues, books (a bible), two globes, bonnets, armor, and various objects from Asia (chinaware), as well as a collections of natural history specimens (two lion skins, a bird-of-paradise, corals and minerals).

[49][50]Two weeks later, Hendrickje and Titus established a dummy corporation as art dealers, allowing Rembrandt, who had board and lodging, to continue his artistic pursuits.

The resulting work, The Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis, was rejected by the mayors and returned to the painter within a few weeks; the surviving fragment (in Stockholm) is only a quarter of the original.

[68] More recent scholarship, from the 1960s to the present day (led by the Rembrandt Research Project), often controversially, has winnowed his oeuvre to nearer 300 paintings.

Modern scholarship has reduced the autograph count to over forty paintings, as well as a few drawings and thirty-one etchings, which include many of the most remarkable images of the group.

His oil paintings trace the progress from an uncertain young man, through the dapper and very successful portrait-painter of the 1630s, to the troubled but massively powerful portraits of his old age.

[k] In his portraits and self-portraits, he angles the sitter's face in such a way that the ridge of the nose nearly always forms the line of demarcation between brightly illuminated and shadowy areas.

[73]In a number of biblical works, including The Raising of the Cross, Joseph Telling His Dreams, and The Stoning of Saint Stephen, Rembrandt painted himself as a character in the crowd.

[74] Among the more prominent characteristics of Rembrandt's work are his use of chiaroscuro, the theatrical employment of light and shadow derived from Caravaggio, or, more likely, from the Dutch Caravaggisti but adapted for very personal means.

[75] Also notable are his dramatic and lively presentation of subjects, devoid of the rigid formality that his contemporaries often displayed, and a deeply felt compassion for mankind, irrespective of wealth and age.

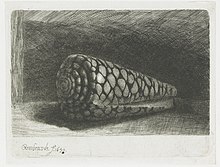

The works encompass a wide range of subject matter and technique, sometimes leaving large areas of white paper to suggest space, at other times employing complex webs of line to produce rich dark tones.

[80] In 1629, he completed Judas Repentant, Returning the Pieces of Silver and The Artist in His Studio, works that evidence his interest in the handling of light and variety of paint application and constitute the first major progress in his development as a painter.

[81] During his early years in Amsterdam (1632–1636), Rembrandt began to paint dramatic biblical and mythological scenes in high contrast and of large format (The Blinding of Samson, 1636, Belshazzar's Feast, c. 1635 Danaë, 1636 but reworked later), seeking to emulate the baroque style of Rubens.

In 1642 he painted The Night Watch, the most substantial of the important group portrait commissions which he received in this period, and through which he sought to find solutions to compositional and narrative problems that had been attempted in previous works.

The result is a richly varied handling of paint, deeply layered and often apparently haphazard, which suggests form and space in both an illusory and highly individual manner.

[89] In later years, biblical themes were often depicted but emphasis shifted from dramatic group scenes to intimate portrait-like figures (James the Apostle, 1661).

[95]In the mature works of the 1650s, Rembrandt was more ready to improvise on the plate and large prints typically survive in several states, up to eleven, often radically changed.

He began to use "surface tone", leaving a thin film of ink on parts of the plate instead of wiping it completely clean to print each impression.

Parts of the canvas were cut off (approximately 20% from the left-hand side was removed) to make the painting fit its new position when it was moved to the town hall in 1715.

Art historians teamed up with experts from other fields to reassess the authenticity of works attributed to Rembrandt, using all methods available, including state-of-the-art technical diagnostics, and to compile a complete new catalogue raisonné of his paintings.

For example, the exact subject being portrayed in Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, recently retitled by curators at the Metropolitan Museum, has been directly challenged by Schama applying the scholarship of Paul Crenshaw.

The book by Bomford[126] describes more recent technical investigations and pigment analyses of Rembrandt's paintings predominantly in the National Gallery in London.

[130] Rembrandt's earliest signatures (c. 1625) consisted of an initial "R", or the monogram "RH" (for Rembrant Harmenszoon), and starting in 1629, "RHL" (the "L" stood, presumably, for Leiden).

Curiously enough, despite the large number of paintings and etchings signed with this modified first name, most of the documents that mentioned him during his lifetime retained the original "Rembrant" spelling.

A partial list should include Ferdinand Bol, Adriaen Brouwer, Gerrit Dou, Willem Drost, Heiman Dullaart, Gerbrand van den Eeckhout, Carel Fabritius, Govert Flinck, Hendrick Fromantiou, Aert de Gelder, Samuel Dirksz van Hoogstraten, Abraham Janssens, Godfrey Kneller, Philip de Koninck, Jacob Levecq, Nicolaes Maes, Jürgen Ovens, Christopher Paudiß, Willem de Poorter, Jan Victors, and Willem van der Vliet.