Return connecting rod engine

Return connecting rod engines were thus rarely used, except in some mid-19th century marine applications where they had certain advantages.

Vertical return connecting rod engines used the original 'vertical' layout, with the cylinder facing upwards to the crosshead.

Trevithick's first high-pressure engines from 1801 onwards, including his locomotives, used the return connecting rod layout in both horizontal and vertical arrangements.

This made the return connecting rod a natural layout, with the crankshaft at the opposite end of the boiler from the crosshead.

These all had heavy vertical cylinders set in tandem within the boiler barrel, driving through transverse crossheads above the locomotive, supported by swinging links.

The swinging link was simpler than Watt's earlier parallel motion and did not constrain the crosshead to move in such an accurate straight line.

For Stephenson's designs, this crank axle would also have carried the locomotive's weight, not being merely a crankshaft, and so this avoided a particularly difficult piece of forging work.

One of the last locomotives to use return connecting rods was Ericsson and Braithwaite's Novelty at the Rainhill trials.

Hedley's Puffing Billy, a contemporary of Blücher, avoided the return connecting rod in favour of a grasshopper beam.

Stephenson's manager Hackworth's locomotive Royal George inverted the design to having the cylinders, still vertical, face downwards directly onto the crankshaft.

Such early engines, constrained by the technology of the time, worked at low boiler pressures and slow piston speeds.

They were popular for early American riverboats and their large wooden A frame crosshead supports were a distinctive feature.

These were more complicated to construct and used more ironwork, but they placed the cylinder beneath the crankshaft and so were more stable in a narrow hull.

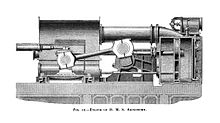

[v] They were mounted transversely, usually as two cylinder engines, and used for naval ships with relatively high installed power.

A trunk engine achieves its short length by having a large diameter, hollow piston rod or 'trunk'.

The connecting rod is only used to drive a flywheel whose inertia balances load through the cycle of the engine, not as an output shaft.

The large vertical blowing engine illustrated was built in the 1890s by E. P. Allis Co. of Milwaukee (later to form part of Allis-Chalmers).

The flywheel shaft is mounted below the steam piston, the paired connecting rods driving downwards and backwards.

Inverted vertical engines had their cylinder at the top and water ram pumps at their base, or in a borehole below them.

Cylinder and piston are to the right, condenser and air pump to the left.