Rhamphorhynchus

[2] Although fragmentary fossil remains possibly belonging to Rhamphorhynchus have been found in England, Tanzania, and Spain, the best preserved specimens come from the Solnhofen limestone of Bavaria, Germany.

[4] The classification and taxonomy of Rhamphorhynchus, like many pterosaur species known since the Victorian era, is complex, with a long history of reclassification under a variety of names, often for the same specimens.

The first named specimen of Rhamphorhynchus was brought to the attention of Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring by the collector Georg Graf zu Münster in 1825.

When further preparation uncovered teeth, Graf zu Münster sent a cast to Professor Georg August Goldfuss, who recognised it as a pterosaur.

[6] Note that the ICZN later ruled that non-standard Latin characters, such as ü, would not be allowed in scientific names, and the spelling münsteri was emended to muensteri by Richard Lydekker in 1888.

Peter Wellnhofer declined to designate a neotype in his 1975 review of the genus, because a number of high-quality casts of the original specimen were still available in museum collections.

[15] Campylognathoides liasicus Campylognathoides zitteli Scaphognathus crassirostris Dorygnathus banthensis Cacibupteryx caribensis Nesodactylus hesperius Rhamphorhynchus muensteri Harpactognathus gentryii Angustinaripterus longicephalus Sericipterus wucaiwanensis Sordes pilosus Monofenestrata The largest known specimen of Rhamphorhynchus muensteri (catalog number NHMUK PV OR 37002) has an estimated wingspan of 1.8 metres (5.9 ft).

[18] However, subsequent examination of this specimen by Wellnhofer in 1975 and Bennett in 2002 using both visible and ultraviolet light found no trace of a crest; both concluded that Broili was mistaken.

Bennett examined two possibilities for hatchlings: that they were altricial, requiring some period of parental care before leaving the nest, or that they were precocial, hatching with sufficient size and ability for flight.

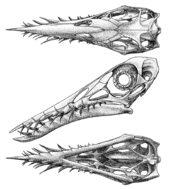

[16] A 2024 paper by David Hone and Skye McDavid described a complete and three dimensional specimen of Rhamphorhynchus, NHMUK PV OR 37002, noted for its abnormally large size.

The back of the skull, meanwhile, was wider, and the lower temporal fenestrae had radically changed shape from a slitlike hole to a wide trapezoidal one.

Similarly, an altered shape of the deltopectoral crest indicates a potential weakened ability to launch into flight from the water.

Especially large and old individuals may have shifted their diet away from fish and cephalopods, with the more powerful skull and cutting teeth potentially used to hunt tetrapods in more terrestrial settings.

This could also explain the lack of such adults within the marine Solnholfen beds, and the large size of NHMUK PV OR 37002 may have in fact been especially unusual amongst unpreserved individuals living in other environments.

Additionally, pterodactyloids had determinate growth, meaning that the animals reached a fixed maximum adult size and stopped growing.

[12] Though Rhamphorhynchus is often depicted as an aerial piscivore, recent evidence suggests that, much like most modern aquatic birds, it probably foraged while swimming.

Both Koh Ting-Pong and Peter Wellnhofer recognized two distinct groups among adult Rhamphorhynchus muensteri, differentiated by the proportions of the neck, wing, and hind limbs, but particularly in the ratio of skull to humerus length.

[13][24] Bennett tested for sexual dimorphism in Rhamphorhynchus by using a statistical analysis, and found that the specimens did indeed group together into small-headed and large-headed sets.

However, without any known variation in the actual form of the bones or soft tissue (morphological differences), he found the case for sexual dimorphism inconclusive.

[12] A 2024 study by Habib and Hone et al., suggests that the high degree of tail variation in mature specimens may represent increased sexual selection in Rhamphorhynchus, though it is equally likely a result of reduced flight constraint.

Using comparisons to modern animals, they were able to estimate various physical attributes of pterosaurs, including relative head orientation during flight and coordination of the wing membrane muscles.

Witmer and his team found that Rhamphorhynchus held its head parallel to the ground due to the orientation of the osseous labyrinth of the inner ear, which helps animals detect balance.

As the Leptolepides was travelling down its pharynx, a large Aspidorhynchus would have attacked from below the water, accidentally puncturing the left wing membrane of the Rhamphorhynchus with its sharp rostrum in the process.

The encounter resulted in the death of both individuals, most likely because the two animals sank into an anoxic layer in the water body, depriving the fish of oxygen.