Abu Bakr al-Razi

Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (full name: أبو بکر محمد بن زکریاء الرازي, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyāʾ al-Rāzī),[a] c. 864 or 865–925 or 935 CE,[b] often known as (al-)Razi or by his Latin name Rhazes, also rendered Rhasis, was a Persian physician, philosopher and alchemist who lived during the Islamic Golden Age.

[3] A comprehensive thinker, al-Razi made fundamental and enduring contributions to various fields, which he recorded in over 200 manuscripts, and is particularly remembered for numerous advances in medicine through his observations and discoveries.

[5] Some volumes of his work Al-Mansuri, namely "On Surgery" and "A General Book on Therapy", became part of the medical curriculum in Western universities.

[5][15][16][17] Because of his newly acquired popularity as physician, al-Razi was invited to Baghdad where he assumed the responsibilities of a director in a new hospital named after its founder al-Muʿtaḍid (d. 902 CE).

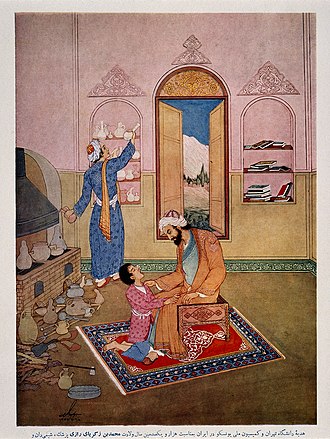

As Ibn al-Nadim relates in Fihrist, al-Razi was considered a shaikh, an honorary title given to one entitled to teach and surrounded by several circles of students.

He was charitable to the poor, treated them without payment in any form, and wrote for them a treatise Man La Yaḥḍuruhu al-Ṭabīb, or Who Has No Physician to Attend Him, with medical advice.

[24] One former pupil from Tabaristan came to look after him, but as al-Biruni wrote, al-Razi rewarded him for his intentions and sent him back home, proclaiming that his final days were approaching.

Additional symptoms are: dryness of breath, thick spittle, hoarseness of the voice, pain and heaviness of the head, restlessness, nausea and anxiety.

At the same time, he warned that even highly educated doctors did not have the answers to all medical problems and could not cure all sicknesses or heal every disease, which was humanly speaking impossible.

To become more useful in their services and truer to their calling, al-Razi advised practitioners to keep up with advanced knowledge by continually studying medical books and exposing themselves to new information.

He also wrote the following on medical ethics: The doctor's aim is to do good, even to our enemies, so much more to our friends, and my profession forbids us to do harm to our kindred, as it is instituted for the benefit and welfare of the human race, and God imposed on physicians the oath not to compose mortiferous remedies.

[32] This monumental medical encyclopedia in nine volumes—known in Europe also as The Large Comprehensive or Continens Liber (جامع الكبير)—contains considerations and criticism on the Greek philosophers Aristotle and Plato, and expresses innovative views on many subjects.

The al-Hawi is not a formal medical encyclopedia, but a posthumous compilation of al-Razi's working notebooks, which included knowledge gathered from other books as well as original observations on diseases and therapies, based on his own clinical experience.

It was translated into Latin in 1279 by Faraj ben Salim, a physician of Sicilian-Jewish origin employed by Charles of Anjou, and after which it had a considerable influence in Europe.

Al-Razi described in its 36 chapters, diets and drug components that can be found in either an apothecary, a market place, in well-equipped kitchens, or and in military camps.

He criticized Galen's theory that the body possessed four separate "humors" (liquid substances), whose balance are the key to health and a natural body-temperature.

Al-Razi's own alchemical experiments suggested other qualities of matter, such as "oiliness" and "sulphurousness", or inflammability and salinity, which were not readily explained by the traditional fire, water, earth, and air division of elements.

Many accused him of ignorance and arrogance, even though he repeatedly expressed his praise and gratitude to Galen for his contributions and labours, saying: I prayed to God to direct and lead me to the truth in writing this book.

[10][11] Al-Razi's interest in alchemy and his strong belief in the possibility of transmutation of lesser metals to silver and gold was attested half a century after his death by Ibn an-Nadim's book, The Philosopher's Stone (Lapis Philosophorum in Latin).

Al-Kindi (801–873 CE) had been appointed by the Abbasid Caliph Ma'mun founder of Baghdad, to 'the House of Wisdom' in that city, he was a philosopher and an opponent of alchemy.

Biographer Khosro Moetazed reports in Mohammad Zakaria Razi that a certain General Simjur confronted al-Razi in public, and asked whether that was the underlying reason for his willingness to treat patients without a fee.

"It appeared to those present that al-Razi was reluctant to answer; he looked sideways at the general and replied":I understand alchemy and I have been working on the characteristic properties of metals for an extended time.

I very much doubt if it is possible...Al-Razi's works present the first systematic classification of carefully observed and verified facts regarding chemical substances, reactions and apparatus, described in a language almost entirely free from mysticism and ambiguity.

Gilding and silvering of other metals (alum, calcium salts, iron, copper, and tutty) are also described, as well as how colors will last for years without tarnishing or changing.

"[55] However, Biruni also listed some other works of al-Razi on religion, including Fi Wujub Da‘wat al-Nabi ‘Ala Man Nakara bi al-Nubuwwat (Obligation to Propagate the Teachings of the Prophet Against Those who Denied Prophecies) and Fi anna li al-Insan Khaliqan Mutqinan Hakiman (That Man has a Wise and Perfect Creator), listed under his works on the "divine sciences".

[57] Adamson states:It is worth noting that Stroumsa’s work predates Rashed’s discovery of this evidence in Fakhr al-Dīn, so that she did not have the benefit of being able to consider how this new information could be reconciled with the Proofs.

I should lay my cards on the table and say that I am persuaded by Rashed’s account, and do not believe that Razi was staging a general attack on prophecy or religion as Abū Ḥātim would have us think.

[59] According to Abdul Latif al-'Abd, Islamic philosophy professor at Cairo University, Abu Hatim and his student, Ḥamīd al-dīn Karmānī (d. after 411AH/1020CE), were Isma'ili extremists who often misrepresented the views of al-Razi in their works.

[60][61] This view is also corroborated by early historians like al-Shahrastani who noted "that such accusations should be doubted since they were made by Ismāʿīlīs, who had been severely attacked by Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyā Rāzī".

[48] In contrast, earlier historians such as Paul Kraus and Sarah Stroumsa accepted that the extracts found in Abu Hatim's book were either said by al-Razi during a debate or were quoted from a now lost work.