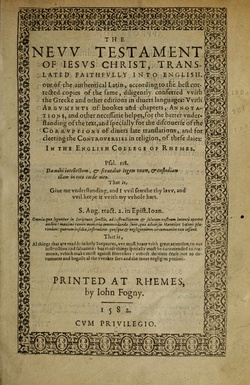

Douay–Rheims Bible

Marginal notes took up the bulk of the volumes and offered insights on issues of translation, and on the Hebrew and Greek source texts of the Vulgate.

The purpose of the version, both the text and notes, was to uphold Catholic tradition in the face of the Protestant Reformation which up until the time of its publication had dominated Elizabethan religion and academic debate.

[4] Following the English Reformation of the later 16th century, under the monarchs of the House of Tudor, some Roman Catholics went in exile to the European continental mainland.

Though he died in the same year as its publication, this translation was principally the work of Gregory Martin, formerly Fellow of St. John's College, Oxford, close friend of Edmund Campion.

He was assisted by others at Douai, notably Allen, Richard Bristow, William Reynolds and Thomas Worthington,[5][6] who proofed and provided notes and annotations.

Worthington, responsible for many of the annotations for the 1609 and 1610 volumes, states in the preface: "we have again conferred this English translation and conformed it to the most perfect Latin Edition.

The Vulgate was largely created due to the efforts of Saint Jerome (345–420), whose translation was declared to be the authentic Latin version of the Bible by the Council of Trent.

To me the least of al the sainctes is given this grace, among the Gentils to evangelize the unsearcheable riches of Christ, and to illuminate al men what is the dispensation of the sacrament hidden from worldes in God, who created all things: that the manifold wisdom of God, may be notified to the Princes and Potestats in the celestials by the Church, according to the prefinition of worldes, which he made in Christ JESUS our Lord.

In whom we have affiance and accesse in confidence, by the faith of him.Other than when rendering the particular readings of the Vulgate Latin, the English wording of the Rheims New Testament follows more or less closely the Protestant version first produced by William Tyndale in 1525, an important source for the Rheims translators having been identified as that of the revision of Tyndale found in an English and Latin diglot New Testament, published by Miles Coverdale in Paris in 1538.

Many highly regarded translations of the Bible routinely consult Vulgate readings, especially in certain difficult Old Testament passages; but nearly all modern Bible versions, Protestant and Catholic, go directly to original-language Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek biblical texts as their translation base, and not to a secondary version like the Vulgate.

Gardiner indeed had himself applied these principles in 1535 to produce a heavily revised version, which has not survived, of Tyndale's translations of the Gospels of Luke and John.

In the preface to the Rheims New Testament the translators criticise the Geneva Bible for their policy of striving always for clear and unambiguous readings; the Rheims translators proposed rather a rendering of the English biblical text that is faithful to the Latin text, whether or not such a word-for-word translation results in hard to understand English, or transmits ambiguity from the Latin phrasings: we presume not in hard places to modifie the speaches or phrases, but religiously keepe them word for word, and point for point, for feare of missing or restraining the sense of the holy Ghost to our phantasie...acknowledging with S. Hierom, that in other writings it is ynough to give in translation, sense for sense, but that in Scriptures, lest we misse the sense, we must keep the very wordes.This adds to More and Gardiner the opposite argument, that previous versions in standard English had improperly imputed clear meanings for obscure passages in the Greek source text where the Latin Vulgate had often tended to rather render the Greek literally, even to the extent of generating improper Latin constructions.

The translators of the Rheims appended a list of these unfamiliar words;[15] examples include "acquisition", "adulterate", "advent", "allegory", "verity", "calumniate", "character", "cooperate", "prescience", "resuscitate", "victim", and "evangelise".

In addition the editors chose to transliterate rather than translate a number of technical Greek or Hebrew terms, such as "azymes" for unleavened bread, and "pasch" for Passover.

Challoner's revisions borrowed heavily from the King James Version (being a convert from Protestantism to Catholicism and thus familiar with its style).

Challoner not only addressed the odd prose and much of the Latinisms, but produced a version which, while still called the Douay–Rheims, was little like it, notably removing most of the lengthy annotations and marginal notes of the original translators, the lectionary table of gospel and epistle readings for the Mass.

At the same time he aimed for improved readability and comprehensibility, rephrasing obscure and obsolete terms and constructions and, in the process, consistently removing ambiguities of meaning that the original Rheims–Douay version had intentionally striven to retain.

In whom we haue affiance and accesse in confidence by the faith of him.The same passage in Challoner's revision gives a hint of the thorough stylistic editing he did of the text: That the Gentiles should be fellow heirs and of the same body: and copartners of his promise in Christ Jesus, by the gospel, of which I am made a minister, according to the gift of the grace of God, which is given to me according to the operation of his power.

To me, the least of all the saints, is given this grace, to preach among the Gentiles the unsearchable riches of Christ: and to enlighten all men, that they may see what is the dispensation of the mystery which hath been hidden from eternity in God who created all things: that the manifold wisdom of God may be made known to the principalities and powers in heavenly places through the church, according to the eternal purpose which he made in Christ Jesus our Lord: in whom we have boldness and access with confidence by the faith of him.For comparison, the same passage of Ephesians in the King James Version and the 1534 Tyndale Version, which influenced the King James Version: That the Gentiles should be fellow heirs, and of the same body, and partakers of his promise in Christ by the gospel: whereof I was made a minister, according to the gift of the grace of God given unto me by the effectual working of his power.

Yet another edition was published in the United States by the Douay Bible House in 1941 with the imprimatur of Francis Cardinal Spellman, Archbishop of New York.

The Challoner revision ultimately fell out of print by the late 1960s, only coming back into circulation when TAN Books reprinted the 1899 Murphy edition in 1971.

A summary list is shown below: The Old Testament "Douay" translation of the Latin Vulgate arrived too late on the scene to have played any part in influencing the King James Version.

Bois records the policy of the review committee in relation to a discussion of 1 Peter 1:7 "we have not thought the indefinite sense ought to be defined"; which reflects the strictures expressed by the Rheims translators against concealing ambiguities in the original text.

More usually, however, the King James Version handles obscurity in the source text by supplementing their preferred clear English formulation with a literal translation as a marginal note.

In 1995, Ward Allen in collaboration with Edward Jacobs further published a collation, for the four Gospels, of the marginal amendments made to a copy of the Bishops' Bible (now conserved in the Bodleian Library), which transpired to be the formal record of the textual changes being proposed by several of the companies of King James Version translators.

This also explains the incorporation into the King James Version from the Rheims New Testament of a number of striking English phrases, such as "publish and blaze abroad" at Mark 1:45.

The Harvard–Dumbarton Oaks editors have been criticized in the Medieval Review for being "idiosyncratic" in their approach; their decision to use Challoner's 18th-century revision of the Douay-Rheims, especially in places where it imitates the King James Version, rather than producing a fresh translation into contemporary English from the Latin, despite the Challoner edition being "not relevant to the Middle Ages"; and the "artificial" nature of their Latin text which "is neither a medieval text nor a critical edition of one.