Georg Joachim Rheticus

Georg Joachim de Porris, also known as Rheticus (/ˈrɛtɪkəs/; 16 February 1514 – 4 December 1574), was a mathematician, astronomer, cartographer, navigational-instrument maker, medical practitioner, and teacher.

Both his parents, Georg Iserin and Thomasina de Porris, were of Italian heritage and possessed considerable wealth, his father being the town physician as well as a government official.

Later as a student at the University of Wittenberg, Georg Joachim adopted the toponym Rheticus, a form of the Latin name for his home region, Rhaetia, a Roman province that had included parts of Austria, Switzerland and Germany.

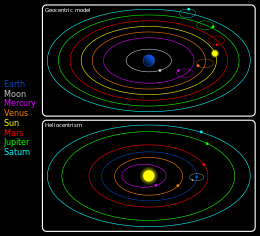

[3] Despite the effort invested thus far, Copernicus had not finished a manuscript of his work, apparently choosing to not seek publication, presumably due to issues reconciling such findings with the historically held religious attitudes at the time.

In September 1539, Rheticus went to Danzig (Gdańsk) to visit the mayor, who gave him financial assistance to publish his Narratio Prima (First Report)[8] of Copernicus' forthcoming treatise.

In it, the origins, flora, and fauna of the country are discussed as well as descriptions for several of its cities, regarding their commerce and history, demonstrating that his travels frequently served a twin purpose.

In August 1541, Rheticus presented both a copy of Chorographia (containing a systematic approach to the preparation of maps, distinguishing chorography from geography, discussing various methods of cartographic survey by the use of the compass as well as improvements to the aforementioned instrument) and Tabula chorographica auff Preussen und etliche umbliegende lender (Map of Prussia and Neighboring Lands) to Albert, Duke of Prussia.

[9] Knowing the duke had been trying to compute the exact time of sunrise, Rheticus made an instrument that determined the length of the day, and through this favor obtained from him a recommendation to Wittenberg that De revolutionibus be published.

In May 1542, he traveled to Nürnberg to supervise the printing by Johannes Petreius of the first edition of De revolutionibus in which he included tables of trigonometric functions he had calculated in further support of Copernicus' work, but had to leave in fall to take a position at the University of Leipzig, and Andreas Osiander replaced him.

A theologian, Osiander would use this role to add an unauthorized preface in a would-be attempt to avoid censorship, explicitly describing the theory discussed therein as a model of pure hypothesis predicated on assumptions that are coincidentally consistent with the calculations.

[12] In a work now properly attributed to Rheticus tentatively titled Epistolae de Terrae Motu (Letter on the Motion of the Earth), he attempts to reconcile Copernicanism with scripture by employing St. Augustine's principle of accommodation.

[13] According to historian Robert Westman, the Epistolae or also known as the Opusculum, published posthumously and anonymously in 1651,[14] demonstrates that Copernicus and Rheticus recognized the problem of conflict between their finding of earthly motion and biblical scripture, and had therefore developed a systematic defense of compatibility.

Considering this tenet, scripture would then lack reference to any specific matter that may be studied by science, such as the movement of the earth with respect to the sun, with the exception being those facts of nature outside mankind's ability to investigate.

[11] Rheticus would further argue that biblical language was written in terms meant to be readily comprehensible to a wide audience: It borrows a kind of discourse, a habit of speech, and a method of teaching from popular usage.While relying heavily upon citations to appease religious authorities, Rheticus may have nevertheless refrained from publishing the work in his life in order to avoid angering more conservative Protestants such as Melanchthon.

According to Meusel, Rheticus "plied him with a strong drink, until he was inebriated; and finally did with violence overcome him and practice upon him the shameful and cruel vice of sodomy".

While there, he continued his work within mathematics and astronomy, further compiling his calculations of trigonomic functions with funding from Emperor Maximilian II with the aid of numerous assistants.