Battle of Rhode Island

The battle was also notable for the participation of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment under the command of Colonel Christopher Greene, which consisted of Blacks, American Indians, and White colonists.

[4] On December 8, 1776, Britain's Lieutenant General Henry Clinton led an expedition from New York City to take control of Rhode Island.

The British expeditionary forces under Brigadier General Richard Prescott, with several Hessian regiments of foot, landed and seized control of Newport, Rhode Island.

[5] France formally recognized the United States of America in February 1778 following the surrender of the British Army after the Battles of Saratoga in October 1777.

It was not until early June that a fleet of 13 ships of the line left European waters in pursuit, under the command of Vice-Admiral John Byron.

[13] While d'Estaing was outside the harbor, British General Henry Clinton and Vice-Admiral Richard Howe dispatched a fleet of transports carrying 2,000 troops to reinforce Newport via Long Island Sound.

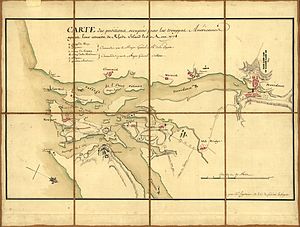

[15] He began logistical preparations for an attack on Newport, caching equipment and supplies on the eastern shore of Narragansett Bay and the Taunton River.

Sullivan did not receive this letter until July 23, and it was followed the next day by the arrival of Colonel John Laurens with word that Newport had been chosen as the allied target on the 22nd Regiment, and that he should raise as large a force as possible.

[19] Laurens had left Washington's camp on the 22nd, riding ahead of a column of Continental troops (the brigades of John Glover and James Mitchell Varnum) led by the Marquis de Lafayette.

[21] Washington sent Major General Nathanael Greene, a Rhode Island native and reliable officer, to further bolster Sullivan's leadership corps on July 27.

[22] D'Estaing sailed from his position outside the New York harbor on July 22, when the British judged the tide high enough for the French ships to cross the bar.

[24] D'Estaing arrived off Point Judith on July 29 and immediately met with Generals Greene and Lafayette to develop their plan of attack.

[25] As allied intentions became clear, General Pigot decided to deploy his forces in a defensive posture, withdrawing troops from Conanicut Island and from Butts Hill.

He also decided to move nearly all livestock into the city, ordered the leveling of orchards to provide a clear line of fire, and destroyed carriages and wagons.

Contrary to the agreement with d'Estaing, Sullivan crossed troops over to seize that high ground, concerned that the British might reoccupy it in strength.

d'Estaing wrote that it was "difficult to persuade oneself that about six thousand men well entrenched and with a fort before which they had dug trenches could be taken either in twenty-four hours or in two days.

[35] He wrote a missive containing much inflammatory language, in which he called d'Estaing's decision "derogatory to the honor of France", and he included further complaints in orders of the day that were later suppressed when tempers had cooled.

[40] Sullivan continued to seek French assistance, dispatching Lafayette to Boston to negotiate further with d'Estaing,[41] but this proved fruitless in the end.

Deserters had made General Pigot aware of the American plans to withdraw on August 26, so he was prepared to respond when they withdrew that night.

Smith's advance stalled when it came under fire from troops commanded by Lt. Col. Henry Brockholst Livingston, who was stationed at a windmill near Quaker Hill.

By 7:30 a.m., Lossberg had advanced against the American Light Corps under Col. John Laurens, who were positioned behind some stone walls south of the Redwood House.

Greene counterattacked with Col. Israel Angell's 2nd Rhode Island Regiment, Brigadier General Solomon Lovell's brigade of Massachusetts militia, and Henry Brockholst Livingston's troops.

According to an account in the New Hampshire Gazette, it was accomplished "in perfect order and safety, not leaving behind the smallest article of provision, camp equipage, or military stores.

"[51] The inflammatory writings of General Sullivan reached Boston before the French fleet arrived, and Admiral d'Estaing's initial reaction was reported to be a dignified silence.

Politicians worked to smooth over the incident under pressure from Washington and the Continental Congress, and d'Estaing was in good spirits when Lafayette arrived in Boston.

The Joseph Reynolds House in Bristol was used by General Lafayette as his headquarters during the campaign; it is a National Historic Landmark and one of the oldest buildings in Rhode Island.