Rhythmic gymnastics

Peter Henry Ling further developed this idea in his 19th-century Swedish system of free exercise, which promoted "aesthetic gymnastics", in which students expressed their feelings and emotions through body movement.

[5] Ling's ideas were extended by Catharine Beecher, who founded the Western Female Institute in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States, in 1837.

[4] Dubbed "harmonic gymnastics", it enabled late nineteenth-century American women to engage in physical culture and expression, especially in dance.

[4][5] The teachings of Duncan, Jacques-Dalcroze, Delsarte, and Demeny were brought together at the Soviet Union's High School of Artistic Movement when it was founded in 1932, and soon thereafter, an early version of rhythmic gymnastics was established as a sport for girls.

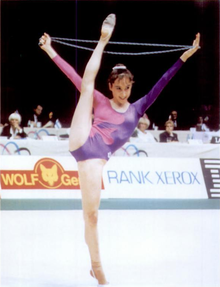

It was painted as a more feminine counterpart to women's artistic gymnastics, where increasingly difficult tumbling led to a perceived masculinization of the sport.

[14] Top rhythmic gymnasts must have good balance, flexibility, coordination, and strength,[16] and they must possess psychological attributes such as the ability to compete under intense pressure and the discipline and work ethic to practice the same skills over and over again.

This is also the case for individuals at some competitions, while at others, there is a separate all-around final round where the top qualifying gymnasts (maximum two per country) compete four routines.

The ideal is for the gymnast to perform with continuous character using a variety of movements that reflect changes in the music and are connected smoothly together.

In the late 90s, there was an appearance of gymnasts whose routines included demonstrating extreme flexibility (Yana Batyrchina or Alina Kabaeva for example).

The 2025–2028 code reduced the maximum number of difficulties counted in the exercise to give more room for artistic expression and transitions between elements.

[17] Beginning in 1997, requirements loosened, and gymnasts were allowed to decorate their leotards with geometric and flower designs, sequins, and metallic colors.

Rhythmic gymnastics has been dominated by Eastern European countries, especially the Soviet Union (Post-Soviet Republics of today) and Bulgaria.

The 1980s marked the height of Bulgarian success with a generation of gymnasts known as the Golden Girls of Bulgaria,[2] with gymnasts Iliana Raeva, Anelia Ralenkova, Lilia Ignatova, Diliana Gueorguieva, Bianka Panova, Adriana Dunavska (the silver medalist at the 1988 Summer Olympics)[62] and Elizabeth Koleva dominating the World Championships.

[60] At the following 2020 Summer Olympics, the group (comprising Simona Dyankova, Laura Traets, Stefani Kiryakova, Madlen Radukanova, and Erika Zafirova) won its first gold medal.

[67] Margarita Mamun continued the streak of individual gold medalists at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics, while the competition favorite, three-time World champion Yana Kudryavtseva, took silver because of a drop in her clubs routine during the finals.

[71] Arina Averina also achieved significant success, consistently earning medals in major international competitions, including the World and European Championships.

[66] Even as part of the USSR, a number of Soviet gymnasts were trained in Ukraine or were of Ukrainian origin, including the first World champion Ludmila Savinkova as well as Liubov Sereda.

[60] Since the late 1990s, Belarus has had continued success in the Olympic Games and has won two silver and two bronze medals in individuals respectively, with Yulia Raskina, Inna Zhukova, Liubov Charkashyna and Alina Harnasko.

Some notable success in rhythmic gymnastics for Spain include Ana Bautista, who won a gold medal in the rope competition in the European Cup final in 1989, Carolina Pascual, the silver medalist at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, Carmen Acedo, who won a gold medal in clubs competition in World Championships in 1993, Almudena Cid, whose four Olympic appearances (1996, 2000, 2004 and 2008) are the most of any rhythmic gymnast,[67] and three-time Olympian Carolina Rodriguez.

The Spanish group was formed by Marta Baldó, Nuria Cabanillas, Estela Giménez, Lorena Guréndez, Tania Lamarca and Estíbaliz Martínez.

[77] The sport began its success in the 2000s with notable Israeli gymnasts including Irina Risenzon and Neta Rivkin, who placed in top ten in the Olympic Games finals.

[82][83] Czechoslovakia dominated the second World Championships, and their routines there, which combined ballet with whole-body movement, influenced the early direction of the sport.

[84] European countries have been always dominant in this sport: only five World Championships have been held outside Europe so far, one in Cuba, one in the US, and three in Japan, and only five individual gymnasts (Sun Duk Jo, Myong Sim Choi, Mitsuru Hiraguchi, Son Yeon-jae, Kaho Minagawa) and three groups (Japan, North Korea and China) from outside Europe have won medals at the World Championships.

Beginning in the 1950s, Evelyn Koop, who graduated from the Ernest Idla Institute in Sweden, promoted the sport in the United States and especially in Canada.

It is thought that this may be in part due to rhythmic gymnasts tending to have looser joints and delayed menarche as well as from repeatedly performing elements using the dominant side of the torso.

In 2021, it was estimated there are about 1,500 participants in Japan, with small individual programs in other countries such as Canada and Russia, and some former gymnasts have moved to the United States to work for Cirque du Soleil.

[11] It may be called by other names in other countries, as the feminine stereotype of the term "rhythmic gymnastics" makes it more difficult to recruit boys into programs.

[111] Proponents of Japanese-style men's rhythmic gymnastics in other countries sometimes emphasize its perceived masculine qualities in contrast with the Spanish or women's version.

[112] In 2013, the Aomori University Men's Rhythmic Gymnastics Team collaborated with renowned Japanese fashion designer Issey Miyake and American choreographer Daniel Ezralow (Spiderman, Cirque du Soleil) to create a one-hour contemporary performance, "Flying Bodies, Soaring Spirits," that featured all 27 Aomori men's rhythmic gymnasts outfitted in Miyake's signature costumes.

"Flying Bodies" was also captured in a 78-minute documentary by director Hiroyuki Nakano that follows the coaches, gymnasts and creative team for the three months leading up to the performance.