Squash (sport)

Later, around 1830, boys at Harrow School noticed that a punctured ball, which "squashed" on impact with the wall, offered more variety to the game.

Students modified their rackets to have a smaller reach and improve their ability to play in these cramped conditions.

[4] In the 20th century, the game increased in popularity with various schools, clubs and private individuals building squash courts, but with no set dimensions.

[3] The rackets were made from one piece English ash, with a suede leather grip and natural gut.

For hardball doubles, the most common variation is an open throat head shape, even balance, and racket weight of 140g.

In the United States, a variant of squash known as hardball was traditionally played with a harder ball and differently sized courts.

[6] They are made with two pieces of rubber compound, glued together to form a hollow sphere and buffed to a matte finish.

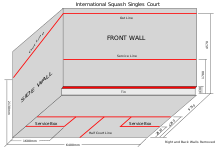

The bottom line of the front wall marks the top of the 'tin', a half meter-high metal area.

The receiving player can choose to volley a serve after it has hit the front wall or may let it bounce.

After the serve, the players take turns hitting the ball against the front wall, above the tin and below the out line.

A key strategy in squash is known as "dominating the T" (the intersection of the red lines near the centre of the court, shaped like the letter "T", where the player is in the best position to retrieve the opponent's next shot).

Boasts or angle shots are deliberately struck off one of the side walls before the ball reaches the front.

Advantageous tactical shots are available in response to a weak return by the opponent if stretched, the majority of the court being free to the striker.

Rallies between experienced players may involve 30 or more shots and therefore a very high premium is placed on fitness, both aerobic and anaerobic.

The ability to change the direction of the ball at the last instant is also a tactic used to unbalance the opponent often called "holding."

Generally, the rules entitle players to a direct straight-line access to the ball, room for a reasonable swing and an unobstructed shot to any part of the front wall.

[15] This system fell out of favor in 2004 when the Professional Squash Association (PSA) decided to switch to PARS to 11.

This scoring system was formerly preferred in Britain, and also among countries with traditional British ties, such as Australia, Canada, Pakistan, South Africa, India and Sri Lanka.

This decision was ratified in 2009 when the World Squash Federation confirmed the switch to the PARS 11 scoring system.

Gawain Briars, who served as the Executive Director of the Professional Squash Association when the body decided to switch to PARS in 2004 hoped that PARS would make the "professional game more exciting to watch, [and] then more people will become involved in the game and our chances of Olympic entry may be enhanced.

Moreover, English or Hi-Ho scoring can encourage players to play defensively with the aim of wearing down one's opponent before winning by virtue of one's fitness.

Such exhausting, defensive play can affect player's prospects in knock-out tournaments and does not make for riveting TV.

[20] The WSF's decision to switch to PARS 11 proved controversial in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth where games were usually played according to English or Hi-Ho.

"[21] Ayton was particularly concerned that the "great comebacks" that characterised English or Hi-Ho when "the player who is down in a game can still attack when in hand serving"[21] would disappear as PARS fostered an "ultra-defensive attitude, because every rally counts the same.

Maj Madan, one of the game's top referees, similarly stated that PARS had "destroyed the fitness element and, more importantly, the cerebral magic of the…game.

Players can expend approximately 600–1,000 food calories (3,000–4,000 kJ) every hour playing squash, according to English or Hi-Ho scoring.

The usual reason cited for the failure of the sport to be adopted for Olympic competition is that it is difficult for spectators to follow the action, especially via television.

The women's championship started in 1921, and it has been dominated by relatively few players:[34] Joyce Cave, Nancy Cave, Cecily Fenwick (England) in the 1920s; Margot Lumb and Susan Noel (England) in the 1930s; Janet Morgan (England) in the 1950s; Heather McKay (Australia) in the 1960s and 1970s; Vicki Cardwell (Australia) and Susan Devoy (New Zealand) in the 1980s; Michelle Martin and Sarah Fitz-Gerald (Australia) in the 1990s; and Nicol David (Malaysia) in the 2000s.

The women's record is held by Nicol David with eight wins followed by Sarah Fitzgerald five, Susan Devoy four, and Michelle Martin three.

Heather McKay remained undefeated in competitive matches for 19 years (between 1962 and 1981) and won sixteen consecutive British Open titles between 1962 and 1977.

2 points during the Semi Final between James Willstrop and Nick Matthew in 2011. [ 11 ] [ 12 ]