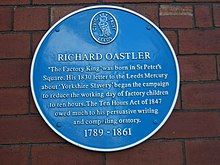

Richard Oastler

[2] When in 1827 the vicar of Halifax (in which parish Fixby lay) attempted to increase his income by "resuming" collection of various tithes which he claimed to be "customary", Oastler was prominent in opposition.

Whilst an existing (virtually un-enforceable) Factory Act specified a minimum age and maximum hours of work for children in cotton mills, it did not apply to other textile industries (such as: silk, flax, woollen and worsted [f]).

The very streets which receive the droppings of an 'Anti-Slavery Society' are every morning wet by the tears of innocent victims at the accursed shrine of avarice, who are compelled (not by the cart-whip of the negro slave-driver) but by the dread of the equally appalling thong or strap of the over-looker, to hasten, half -dressed, but not half-fed, to those magazines of British infantile slavery the worsted mills in the town and neighbourhood of Bradford!!!

This triggered correspondence; it became clear that other readers of the Mercury were also perturbed at conditions for children not only in the worsted industry, but also in other unregulated textile trades carried out in the West Riding.

Oastler took great exception to this; the Leeds Intelligencer, the great (Tory) rival of the (Whig) Mercury was happy to print the letter in full, including such passages as:[2]: 77 Resolution 3 – attempts to persuade the public that if the manufacturers are not allowed to continue their present cruelties, the children will be starved and unemployed, and that, as these poor children are the main support of their strong and healthy parents, why, forsooth, the parents must starve too!

Thus destroying at one fell swoop the maker, the buyer, the consumer – both the home and foreign markets will be lost – the agricultural and landed proprietor ruined:- all this they say will be the consequences if poor little English children are protected from the cruelty and oppression of their worse than Egyptian task-masters.

The Short Time movement saw no need for further investigation and Lord Ashley – now the champion of factory reform in the Commons – introduced another Ten-Hour Bill without waiting for the Commission's report.

The short time committees of the textile districts organised mass demonstrations for a Ten-Hour Act, the rhetoric becoming more heated ("Tt is a question of blood against gold.

Despite winning a number of Parliamentary votes, Ashley was unable to secure a majority for key clauses in his Bill, and withdrew it, leaving the way open for Lord Althorp to pilot through a Factory Act in line with the Commission recommendations.

[22]: 56 Mill-owners (whether reconciled to the principle of state intervention or not) objected that the textile districts did not have the significant pool of unemployed children needed for a 'relay system': it was therefore virtually impossible to attempt to comply with the Act.

The government Bill was withdrawn after it secured a majority of only two at Second Reading; the campaign for a Ten-Hour Act continued, but was seriously set back by a speech Oastler made at Blackburn in September 1836.

The Blackburn Standard (a friend of the Ten-Hour Bill) published only an expurgated account of the meeting at which Oastler spoke, preceding it with an editorial in which they deplored the speeches of him and his fellow orators: Such of the sentiments to which they gave utterance, as we deem safe to publish, we report at some length in other columns, but we must say, that they delivered a vast deal of empty, impudent, nonsensical, mischievous, and disgusting balderdash, which we consider it to be our duty to exclude altogether from the Standard.

We do not hesitate to aver that they have, in one night, done more injury to the cause of the factory operatives in this town, by the disgraceful advice which they tendered to their hearers ... than the true friends of the people can repair by the most strenuous attention for many months.

It is not surprising that Christian ministers decline to join in a crusade where the leaders are utterly devoid of Christian charity, and reckless of the consequences of their violence[23]The Standard therefore did not report that Oastler had talked of teaching children to sabotage mill machinery,;[2]: 327 this was however seized upon by his opponents such as the Manchester Guardian [j] which urged that either 'his friends should put him under some restraint' or 'the law should interpose to end the career of wickedness which he seems disposed to run'.

In the preface to this speech, Oastler denounced the Poor Law Amendment Act as an unjust, unChristian measure, declaring CHRISTIAN READER Be not alarmed at the sound of the Title.

[31] The chairman of the Commission was Sir Thomas Frankland Lewis, an exact contemporary of Thornhill at Eton The new dispensation was implemented progressively, starting with the southern counties of England, where it achieved a considerable reduction in the poor rates.

[34] A fresh election was held in July (Parliament automatically being dissolved on the death of King William IV); Oastler stood again at Huddersfield, and was again defeated by 22 votes by a different Whig opponent.

That could only lead to assassinations; better by far to arm openly, as was their right; the government and the poor law administrators would then treat them more civilly: "I would recommend you, every one, before next Saturday night, to have a brace of horse pistols, a good sword and a musket, and to hang them up on your mantelpieces (not by any means to use them).

[9]: 202–208 [13] Oastler had previously told other anti-Poor Law campaigners that Frankland Lewis was urging Thornhill to sack him, and his dismissal was described in various sympathetic papers as "the rewards of independent resistance of Whig tyranny".

[2]: 413 [q] Oastler's imprisonment brought reconciliation with former allies who had broken with him, and visits and gifts not only from his supporters from every class but also from political opponents who thought Thornhill's conduct oppressive.

"[49] In prison Oastler wrote (weekly) his "Fleet Papers", ostensibly letters addressed to Thornhill reviewing current political affairs, published and sold for 2d per issue .

This was the only means by which he could earn money, and the only way he could continue to resist the advances of 'political economy': "I can only now aid by my pen; but I will strive to do the duty of an Englishman, and, "whether they will hear or they will forbear," I will warn the people of the danger to which the Liberal schemes of the self-styled Free-trading Philosophers must eventually lead them.[8]: 194 ".

This had not been successful, and on Oastler's imprisonment transformed itself into an 'Oastler Liberation Fund'; this initially also stalled well short of its target[2]: 440 [s] until relaunched in the summer of 1843 by an editorial in The Times, followed by fund-raising meetings held across the factory districts and reported nationally.

In July 1844, having been advised by his Liberation Committee that money was not forthcoming to support him in public life,[52] he advertised himself in Leeds papers as "Umpire, Arbitrator, Agent for the Purchase or Sale of Estates, and for Obtaining or Opposing Private Bills in Parliament".

In the autumn of 1846 he was summoned from retirement, by the West Riding Short-Time Committee, to be the principal speaker at public meetings to demonstrate the millworkers' continuing support for a Ten-Hour Act;[60] following this he undertook a similar speaking tour of textile areas in Scotland.

[61] He continued to argue for Protection, and against Free Trade and the "Manchester School", but his appearances at Short Time meetings were now to receive congratulatory addresses, to reminisce, and to pay tribute to former colleagues in the struggle.

[11] He was buried in the family vault at Kirkstall, Leeds: he had asked for a simple and private funeral, but many of his old Short Time comrades attended and at their insistence the coffin was carried by twelve factory workers.

[64] At the nadir of Oastler's fortunes in 1840, the Leeds Intelligencer told its readers "Important religious, moral, and social consequences have been the fruits of his herculean labours, and it is probable that posterity will decree him a statue".

The ten-hour day was now accepted as normal and proper: consequently it was now passing from remembrance that "the agitation in favour of it was by no means well received, and the struggle that won it was a hard one".

A public house (previously a chapel) in Park Street Market, Brighouse, and a school in the Armley district of Leeds, West Yorkshire, also bear his name.