Richard Roose

King Henry VIII—who already had a morbid fear of poisoning—addressed the House of Lords on the case and was probably responsible for an act of parliament which attainted Roose and retroactively made murder by poison a treasonous offence mandating execution by boiling.

Henry eventually broke with the Catholic Church and married Boleyn, but his new Act against Poisoning did not long outlive him, as it was repealed almost immediately by his son Edward VI.

[note 1] Although various laws had sought to restrict appeal to church courts since the 14th century, this was generally on limited terms against a small number of clergy in individual cases.

[8] In January 1531, Fisher was briefly arrested for praemunire, for example, and two months later he was made physically ill at Wiltshire's boast that he could legally, and backed by scripture, disprove the theory of Papal primacy.

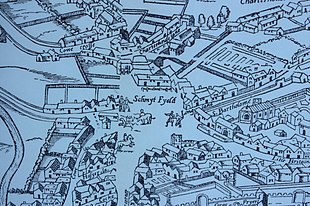

[21][note 4] A later act of parliament described the official account of events, stating that[23] On the Eighteenth day of February, 1531, one Richard Roose, of Rochester, Cook, also called Richard Cooke, did cast poison into a vessel, full of yeast or barm, standing in the kitchen of the Bishop of Rochester's Palace [sic], at Lambeth March, by means of which two persons who happened to eat of the pottage made with such yeast died.

[26] Fisher, who had not partaken of the dish, survived, but about 17 people were violently ill.[18] The victims included both members of his dining party that day and the poor who regularly came to beg charity from his kitchen door.

[3][30] His abstinence may also have been due, suggests Bernard, to Fisher's well known charitable practice of not eating before the supplicants at his door had; as a result, they played the accidental role of food tasters for the Bishop.

[8] Roose himself claimed that the white[1] powder would cause discomfort and illness but would not be fatal and that the intention was merely to tromper Fisher's servants with a purgative,[21] a theory also supported by Chapuys at the time.

[8] The scholar John Matusiak argues that "no other critic of the divorce among the kingdom's elites would, in fact, be more outspoken and no opponent of the looming breach with Rome would be treated to such levels of intimidation" as Fisher until his 1535 beheading.

[40] It is likely that although Henry was determined to bring England's clergy directly under his control—as his laws against praemunire demonstrated—the situation had not yet worsened to the extent that he wanted to be seen as an open enemy of the church or its senior echelons.

[15] Chapuys originally suggested this possibility to the Emperor in his March letter, telling Charles that "the king has done well to show dissatisfaction at this; nevertheless, he cannot wholly avoid some suspicion, if not against himself, whom I think too good to do such a thing, at least against the lady and her father".

The medievalist Alastair Bellany argues that, to contemporaries, while the involvement of the King in such an affair would have been incredible, "poisoning was a crime perfectly suited to an upstart courtier or an ambitious whore"[42] such as she was portrayed by her enemies.

[42] The Spanish Jesuit Pedro de Ribadeneira—writing in the 1590s—placed the blame firmly on Boleyn herself, writing how she had hated Rochester ever since he had taken up Catherine's cause so vigorously and her hatred inspired her to hire Roose to commit murder.

[44] While he was imprisoned, the King addressed the lords of parliament on 28 February[30] for an hour and a half, mostly on the poisonings,[21] "in a lengthy speech expounding his love of justice and his zeal to protect his subjects and to maintain good order in the realm" comments the historian William R.

[32] Such a highly public response based on the King's opinions rather than legal basis,[45]—was intended to emphasise Henry's virtues, particularly his care for his subjects and upholding of "God's peace".

[21] The King, in his speech, emphasised that[55] His Highnes...considering that mannes lyfe above all thynges is chiefly to be favoured, and voluntary murderes moste highly to be detested and abhorred, and specyally of all kyndes of murders poysonynge, Which in this Realme hitherto the Lorde be thanked hath ben moste rare and seldome comytted or practysed...[56]Henry's essentially ad hoc augmentation of the Law of Treason has led historians to question his commitment to common law.

[28] Stacy comments that "traditionally, treason legislation protected the person of the King and his immediate family, certain members of the government, and the coinage, but the public clause in Roose's attainder offered none of these increased security".

[62] As a result of the deaths at Fisher's house, parliament—probably at the King's insistence[63]—ensured that the Acte determined that murder by poison would henceforth be treason, to be punished by boiling alive.

[72]The main result, in Hall's words, was that Fisher "perceived that great malice was meant toward him",[72][8] notes Bernard, and declared his intention to leave for Rochester immediately.

[3] Chapuys suggested that Fisher's removal from Westminster would be harmful to his cause, writing to Charles that "if the King desired to treat of the affair of the Queen, the absence of the said Bishop ... would be unfortunate".

[18] The scholar Suzannah Lipscomb has noted that, whereas attempting to kill a Bishop in 1531 was punishable by a painful death, it was "an irony perhaps not lost on others four years later",[84] when Fisher was sent to the block, also under the new treason laws.

[63] As Bellany notes, while the statute "had long been repealed, Bacon could still describe poisoning as a kind of treason"[63] on account of his view that it was an attack on the body politic, charging that it was "grievous beyond other matters".

[59] Bellany suggests that the case "starkly revealed the poisoner's unnerving power to subvert the order and betray the intimacies that bound household and community together",[12] the former being viewed simply as a microcosm of the latter.

The secrecy with which the lower-class could subvert their superior's authority, and the wider damage this was seen to do, explains why the Acte directly compares poisoning as a crime with that of coining, which harmed not just the individuals subject to the con, but the economy generally.

[12] The historian Penry Williams suggests that the Roose case, and particularly the elevation of poisoning to a crime of high treason, is an example of a broader, more endemic, extension of capital offences under Henry VIII.

[47] The Tudor historian Geoffrey Elton suggested that the 1531 act "was in fact the dying echo of an older common law attitude which could at times be negligent of the real meaning" of attainder.

[93] Kesselring disputes this interpretation, arguing that, far from being an accidental throwback, the act deliberately intended to circumvent common law, so avoiding politically sensitive cases becoming dealt with by judges.

[94] This, the legal scholar John Bellamy suggests, may have been Henry's means of persuading the Lords to support the measure, as in most cases they could expect to receive the goods and chattels of the convicted.

[96] Stacy, arguing that the Roose case is the first example of an attainder intended to avoid dependency on common law,[61] states that although it has been overshadowed by subsequent higher profile individuals, it remained the legal precedent for those prosecutions.

Talk about poison crystallized profound (and growing) contemporary anxieties about order and identity, purity' and pollution, class and gender, self and other, the domestic and the foreign, politics and religion, appearance and reality, the natural and the supernatural, the knowable and the occult.