Rifamycin

Rifamycin, sold under the trade name Aemcolo, is approved in the United States for treatment of travelers' diarrhea in some circumstances.

Then, in 1986, the bacterium was renamed again Amycolatopsis mediterranei, as the first species of a new genus, because a scientist named Lechevalier discovered that the cell wall lacks mycolic acid and is not able to be infected by the Nocardia and Rhodococcus phages.

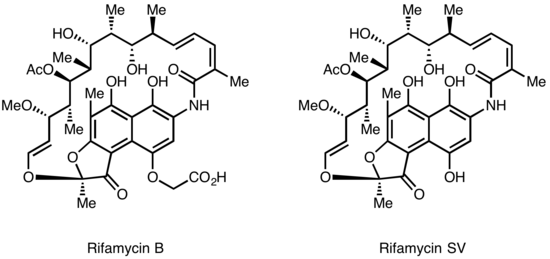

Further chemical modification of Rifamycin SV yielded an improved analog Rifamide, which was also introduced into clinical practice, but was similarly limited to intravenous use.

After an extensive modification program, Rifampin was eventually produced, which is orally available and has become a mainstay of Tuberculosis therapy[4] Lepetit filed for patent protection of Rifamycin B in the UK in August 1958, and in the US in March 1959.

[6] The rifamycins have a unique mechanism of action, selectively inhibiting bacterial DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and show no cross-resistance with other antibiotics in clinical use.

Rifampin rapidly kills fast-dividing bacilli strains as well as "persisters" cells, which remain biologically inactive for long periods of time that allow them to evade antibiotic activity.

Crystal structure data of the antibiotic bound to RNA polymerase indicates that rifamycin blocks synthesis by causing strong steric clashes with the growing oligonucleotide ("steric-occlusion" mechanism).

[9][10] If rifamycin binds the polymerase after the chain extension process has started, no inhibition is observed on the biosynthesis, consistent with a steric-occlusion mechanism.

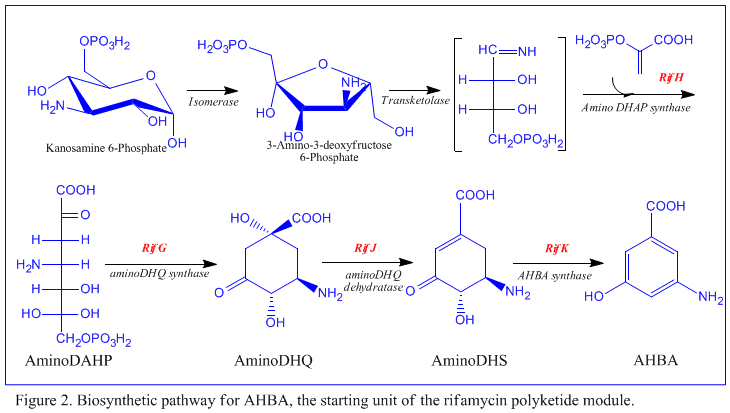

The first information on the biosynthesis of the rifamycins came from studies using the stable isotope Carbon-13 and NMR spectroscopy to establish the origin of the carbon skeleton.

The naphthalenic chromophore was shown to derive from a propionate unit coupled with a seven carbon amino moiety of unknown origin.

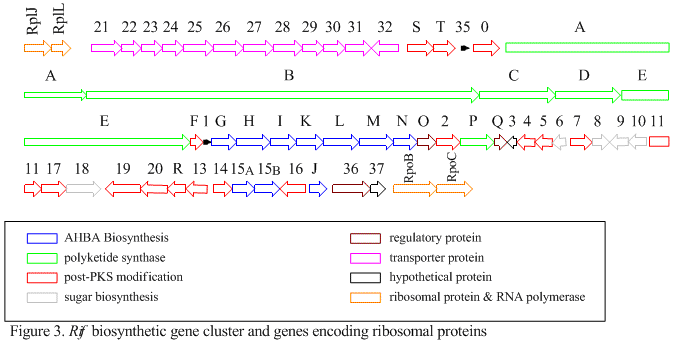

[10] RifK, rifL, rifM, and rifN are believed to act as transaminases in order to form the AHBA precursor kanosamine.