Right to die

The right to die is a concept rooted in the belief that individuals have the autonomy to make fundamental decisions about their own lives, including the choice to end them or undergo voluntary euthanasia, central to the broader notion of health freedom.

This right is often associated with cases involving terminal illnesses or incurable pain, where assisted suicide provides an option for individuals to exercise control over their suffering and dignity.

The debate surrounding the right to die frequently centers on the question of whether this decision should rest solely with the individual or involve external authorities, highlighting broader tensions between personal freedom and societal or legal restrictions.

Religious views on the matter vary significantly, with some traditions such as Hinduism (Prayopavesa) and Jainism (Santhara), permitting non-violent forms of voluntary death, while others, including Catholicism, Islam, and Judaism, consider suicide a moral transgression.

Physician-assisted suicide advocate Ludwig Minelli, euthanasia expert Sean W. Asher, and bioethics professor Jacob M. Appel, in contrast, argue that all competent people have a right to end their own lives.

[6] A professor in social work, Alexandre Baril, proposed to create an ethic of responsibility "based on a harm-reduction, non-coercive approach to suicide.

Since human beings do not have the power to act at the time of their birth, no one should have authority over a person's decision to continue living or to die.

For example, Avital Pilpel and Lawrence Amsel argue:[13] "Contemporary advocates of rational suicide or the right to die generally demand, for reasons of rationality, that the decision to end one's life be an autonomous choice of the individual (i.e., not due to pressure from doctors or family to 'do what is right' and commit suicide), that the choice be 'the best option in these circumstances' (desired by Stoics or utilitarians), as well as other natural conditions, such as the stability of the decision, the absence of impulsivity, the absence of mental illness, deliberation, etc."

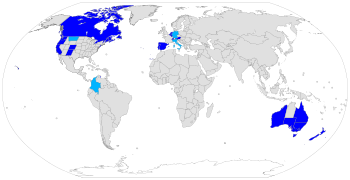

As of 2023, some forms of voluntary euthanasia are legal in Australia, Belgium,[14] Canada,[15] Colombia,[15] Luxembourg,[16] the Netherlands,[14] New Zealand, Spain and Switzerland.

[14] As euthanasia is a health issue, under the Australian constitution this falls to state and territory governments to legislate and manage.

[29] The Canadian Medical Association (CMA) reported that not all doctors were willing to assist in a patient's death due to legal complications and went against what a physician stood for.

[33] On 15 December 2014, the Constitutional Court had given the Ministry of Health and Social Protection 30 days to publish guidelines for the healthcare sector to use in order to guarantee terminally ill patients, with the wish to undergo euthanasia, their right to a dignified death.

Under Dutch law, euthanasia and assisted suicide can only be performed by doctors, and that is only legal in cases of "hopeless and unbearable" suffering.

In practice, this means that it is limited to those with serious and incurable medical conditions (including mental illness) and in considerable suffering like pain, hypoxia or exhaustion.

[42] In May 2018, a Gallup poll report announced that 72% of responders said that doctors should legally be allowed to help terminally ill patients die.

[46] The right to die movement in the United States began with the case of Karen Quinlan in 1975 and continues to raise bioethical questions about one's quality of life and the legal process of death.

[48][47] Quinlan did not have a proxy or living will and had not expressed her wishes if something ever happened to her to those around her, which made it difficult to decide what the next step should be.

[47][49] Her father sought out the right to be Quinlan's legal guardian and petitioned for the removal of the respirator that was keeping her alive.

The court, however, argued that the removal of the ventilator, which would lead to Quinlan's death, would be considered unlawful, unnatural, and unethical.

[51] Another major case that further propagated the right to die movement and the use of living wills, advance directives and use of a proxy was Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health.

Her status as an adult and lack of an advance directive, living will, or proxy led to a long legal battle for Cruzan's family in petitioning for the removal of her feeding tube, which was keeping her alive since the accident.

Cruzan had mentioned to a friend that under no circumstances would she want to continue to live if she were ever in a vegetative state, but this was not a strong enough statement to remove the feeding tube.

[53] This brought up bioethical debates on the discontinuation of Schiavo's life vs. allowing her to continue living in a permanent vegetative state.

[53][55] As the health of citizens is considered a police power left for individual states to regulate, it was not until 1997 that the US Supreme Court made a ruling on the issue of assisted suicide and one's right to die.

In 2009, the Montana Supreme Court ruled that nothing in state law prohibits physician-assisted suicide and provides legal protection for physicians in the case that they prescribe lethal medication upon patient request.

[63] The ultimate decision will be made with the outcome of New Mexico's Attorney General's appeal to the ruling.

Organizations have been continuously pushing for the legalization of self-determination in terminally ill patients in states where the right to end one's life is prohibited.

[65] The role of physicians in patient's right to die is debated within the medical community, however, the AMA provided an opinion statement on the matter.

These are recommendations for physicians from the Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 5.7[66] regarding end of life care: Hinduism accepts the right to die for those who are tormented by terminal diseases or those who have no desire, no ambition, and no responsibilities remaining.