Ring shout

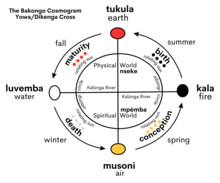

[2] Certain authors claim that the ring shout may be inspired by cultural practices in Africa that became incorporated as a part of Christian worship and imbued with new theological meaning.

[5] The ring shout has been practiced in some Black churches into the 20th century, and it continues to the present among the Gullah people of the Sea Islands and in "singing and praying bands" associated with many Methodist congregations in Tidewater Maryland and Delaware, which have a large African American membership.

Robert Palmer states that it "developed with the widespread conversion of slaves to Christianity during the revival fervors of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

[15] In some cases, enslaved people retreated into the woods at night to perform shouts, often for hours at a time, with participants leaving the circle as they became exhausted.

[16][17] In the twentieth century, churchgoers (especially those of the Methodist and Pentecostal traditions) in the United States performed shouts by forming a circle around the pulpit, in the space in front of the altar, or around the nave.

[27] A minority of scholars have suggested that the ritual may have originated among enslaved Muslims from West Africa as an imitation of tawaf, the mass procession around the Kaaba that is an essential part of the Hajj.

[28][29] Sterling Stuckey in his book, Slave Culture: Nationalist Theory & the Foundations of Black America (1987, ISBN 0195042654) argues that ring shout was a unifying element of Africans in American colonies, from which field hollers, work songs, and spirituals evolved, followed by blues and jazz.

Though augmented and interracialized by the Pentecostal tradition in the early 1900s and spreading to various denominations and churches thereafter, it is still primarily practiced among Christians of West African descent.