Ringing rocks

[1] At the 13th Annual meeting of the Bucks Historical Society in June 1900, Charles Laubach, a noted local geologist and naturalist, described the geology of the diabase "trap" sills with reference to sites such as Bridgeton, Stony Garden, and others.

[4] Although there have been over a dozen diabase ringing rock boulder fields identified in the Pennsylvania and New Jersey area,[5][full citation needed] the majority are either on private property or have been obliterated by urban development.

Apparently, Haring wished to protect the ringing rocks from development, and even refused an offer from a manufacturer of Belgian blocks for the right to quarry the stones.

[10] The Stony Garden, largest of the three public ringing rock boulder fields, is located on the northwest slope of Haycock Mountain in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, near Bucksville.

The garden is actually a series of disconnected boulder fields which extend for nearly half a mile, and were formed where the olivine diabase unit crops out along the base of the mountain.

The site is undeveloped, and is accessible by a hiking trail which leads from a PA Game Lands parking area on Stony Garden Road.

The rocks weighed approximately 200 lb (91 kg) apiece, and apparently Ott was able to change their sound by slightly chipping the boulders.

[12] These boulder fields in southeastern Pennsylvania and central New Jersey formed from a group of diabase sills in Newark Basin.

The sills were formed when stretching of the Earth's crust allowed mafic magma to travel up from the upper mantle inject into the sedimentary basin 200 million years ago (early Jurassic Period).

Phenocrysts of two minerals that had crystallized in the upper mantle, olivine and pyroxene, quickly settled out of the magma and collected along the base of the sills.

Although the Newark series diabase sills crop out in a belt throughout the length of the Appalachian Mountains, only a narrow band of outcrops in southeastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey develop ringing rock boulder fields.

Frost wedging breaks up the upper portion of the rock formation, and the slight dip of the field allows the fine weathering materials to be flushed away before soil can develop.

This specific dip-slope situation allowed broad expanses of olivine diabase to be exposed and provided enough material to create the fields.

There has been a great deal of controversy concerning the ringing ability of the boulders; conversely, there has been an almost complete lack of testing to support the conjectures.

Actual chemical analysis of the Coffman Hill diabase[13] shows that iron content (as ferric oxide) of the rock ranges from 9% and 12%.

In the 1960s, a Rutgers University professor did an informal experiment where specimens of "live" and "dead" ringing rock boulders from the Bucks County park site were sawed into thin slices and then measured for changes in shape.

The professor went on to make the observation that the live rocks were generally found toward the middle of the boulder fields, where they did not come in contact with soil and the shade of the surrounding trees.

He then theorized that the slow weathering rate in the dry "microclimate" of the fields caused the stresses, because the outside skin of the boulders would expand owing to the conversion of pyroxene to montmorillonite (a clay mineral).

The result of such a situation would be that the outside skin of the boulders would peel or exfoliate, a condition that is virtually non-existent in any of the ringing rocks sites.

Furthermore, if slow weathering created the stresses, then there would be ringing rock boulder fields in deserts throughout the world, a condition which does not occur.

The effects of these stresses can be seen in deep mines with a depth of over a mile, where the sudden decompression creates rock bursts.

The probable source of these textures was chemical weathering along joint surfaces when the rock was still in place and before the boulders were broken out by frost heaving.

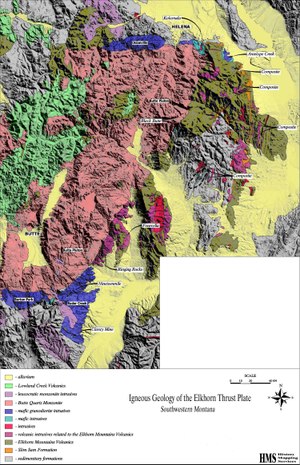

The Ringing Rocks Pluton is located on the southwestern flank of Dry Mountain in Jefferson County, 15 miles southeast of Butte in T.2 N., R.5 W., sections 4 and 9.

The rock that retained the olivine and pyroxene crystals (OPM) is extremely resistant to weathering and is the material which forms the tors.

A series of radial dikes punctured the mafic units, beginning in the felsic zone and terminating at the outer border of the intrusion.

Intense freezing and thawing during the Pleistocene periglacial period slowly shattered the walls, much like breaking tempered glass.

At the north end of the pluton the orientation of the OPM units was at an acute angle to the Dry Creek drainage so that the tor there did not develop very well.

Boulders of the olivine pyroxene monzonite develop odd surface weathering patterns, similar to the textures seen in the Pennsylvania diabase ringing rocks.

The Bell Rock Range is a large ultramafic gabbro-peridotite intrusion in the Musgrave Block of Western Australia, near Warburton, 40 kilometres (25 mi) south of the Wingellina community in the Ngaanyatjarra lands.

[19] It is composed of massive, heavily indurated intrusive rocks and forms a prominent 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) long range of mountains and hills.