Ritual

[8] The word "ritual" is first recorded in English in 1570, and came into use in the 1600s to mean "the prescribed order of performing religious services" or more particularly a book of these prescriptions.

[10][11][12] Catherine Bell argues that rituals can be characterized by formalism, traditionalism, invariance, rule-governance, sacral symbolism and performance.

Maurice Bloch argues that ritual obliges participants to use this formal oratorical style, which is limited in intonation, syntax, vocabulary, loudness, and fixity of order.

[14] Rituals appeal to tradition and are generally continued to repeat historical precedent, religious rite, mores, or ceremony accurately.

An example is the American Thanksgiving dinner, which may not be formal, yet is ostensibly based on an event from the early Puritan settlement of America.

[21] The performance of ritual creates a theatrical-like frame around the activities, symbols and events that shape participant's experience and cognitive ordering of the world, simplifying the chaos of life and imposing a more or less coherent system of categories of meaning onto it.

[28] These rites may include forms of spirit divination (consulting oracles) to establish causes—and rituals that heal, purify, exorcise, and protect.

To correct the balance of matrilinial descent and marriage, the Isoma ritual dramatically placates the deceased spirits by requiring the woman to reside with her mother's kin.

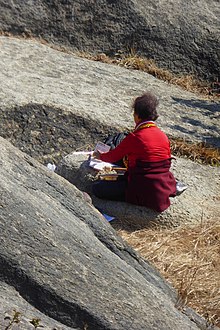

In Tibetan Buddhism, for example, the rituals described in the Bardo Thodol guide the soul through the stages of death, aiming for spiritual liberation or enlightenment.

Indigenous cultures may have unique practices, such as the Australian Aboriginal smoking ceremony, intended to cleanse the spirit of the departed and ensure a safe journey to the afterlife.

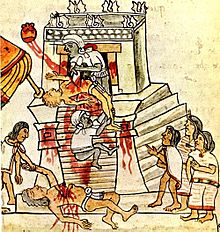

[35] Mircea Eliade states that the calendrical rituals of many religious traditions recall and commemorate the basic beliefs of a community, and their yearly celebration establishes a link between past and present, as if the original events are happening over again: "Thus the gods did; thus men do.

It encompasses a range of performances such as communal fasting during Ramadan by Muslims; the slaughter of pigs in New Guinea; Carnival festivities; or penitential processions in Catholicism.

Yet outside carnival, social tensions of race, class and gender persist, hence requiring the repeated periodic release found in the festival.

In such religio-political movements, Islanders would use ritual imitations of western practices (such as the building of landing strips) as a means of summoning cargo (manufactured goods) from the ancestors.

Leaders of these groups characterized the present state (often imposed by colonial capitalist regimes) as a dismantling of the old social order, which they sought to restore.

[46] Rituals may also attain political significance after conflict, as is the case with the Bosnian syncretic holidays and festivals that transgress religious boundaries.

Although the functionalist model was soon superseded, later "neofunctional" theorists adopted its approach by examining the ways that ritual regulated larger ecological systems.

Rappaport concluded that ritual, "...helps to maintain an undegraded environment, limits fighting to frequencies which do not endanger the existence of regional population, adjusts man-land ratios, facilitates trade, distributes local surpluses of pig throughout the regional population in the form of pork, and assures people of high quality protein when they are most in need of it".

The rites ultimately functioned to reinforce social order, insofar as they allowed those tensions to be expressed without leading to actual rebellion.

He observed, for example, how the first-fruits festival (incwala) of the South African Bantu kingdom of Swaziland symbolically inverted the normal social order, so that the king was publicly insulted, women asserted their domination over men, and the established authority of elders over the young was turned upside down.

[56] Claude Lévi-Strauss, the French anthropologist, regarded all social and cultural organization as symbolic systems of communication shaped by the inherent structure of the human brain.

[58] Mary Douglas, a British Functionalist, extended Turner's theory of ritual structure and anti-structure with her own contrasting set of terms "grid" and "group" in the book Natural Symbols.

[59] (see also, section below) In his analysis of rites of passage, Victor Turner argued that the liminal phase - that period 'betwixt and between' - was marked by "two models of human interrelatedness, juxtaposed and alternating": structure and anti-structure (or communitas).

Drawing on Van Gennep's model of initiation rites, Turner viewed these social dramas as a dynamic process through which the community renewed itself through the ritual creation of communitas during the "liminal phase".

Like Gluckman, he argued these rituals maintain social order while facilitating disordered inversions, thereby moving people to a new status, just as in an initiation rite.

He also differed from Gluckman and Turner's emphasis on ritual action as a means of resolving social passion, arguing instead that it simply displayed them.

The shift in definitions from script to behavior, which is likened to a text, is matched by a semantic distinction between ritual as an outward sign (i.e., public symbol) and inward meaning.

This ritual united the school and created a sense of solidarity and community on a weekly basis involving pep rallies and the game itself.

He described Friday Night Lights as a ritual that overcomes those differences: "The other, gentler, more social side of football was, of course, the emphasis on camaraderie, loyalty, friendship between players, and pulling together".

[91] The degrees of Freemasonry derive from the three grades of medieval craft guilds; those of "Entered Apprentice", "Journeyman" (or "Fellowcraft"), and "Master Mason".