Scriptorium

Monks copied Jerome's Latin Vulgate Bible and the commentaries and letters of early Church Fathers for missionary purposes as well as for use within the monastery.

Recent studies follow the approach, that scriptoria developed in relative isolation, to the extent that paleographers are sometimes able to identify the product of each writing centre and to date it accordingly.

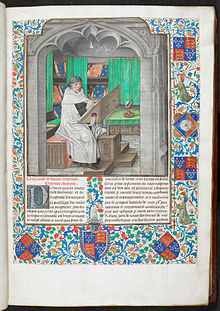

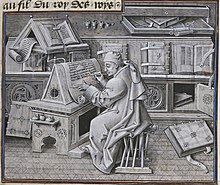

[7] By the start of the 13th century, secular workshops developed,[8] where professional scribes stood at writing-desks to work the orders of customers, and during the Late Middle Ages the praxis of writing was becoming not only confined to being generally a monastic or regal activity.

Archaeologists identified lapis lazuli, a pigment used in the decoration of medieval illuminated manuscripts, embedded in the dental calculus of remains found in a religious women's community in Germany, which dated to the 11th-12th centuries.

[10] Chelles Abbey, established in France during the early medieval period, was also well known for its scriptorium, where nuns produced manuscripts and religious texts.

[12] There were also women who worked as professional, secular scribes, including Clara Hätzlerin in 15th century Augsburg, who has at least nine surviving manuscripts signed by or attributed to her.

[13] Much as medieval libraries do not correspond to the exalted sketches from Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose,[15] it seems that ancient written accounts, as well as surviving buildings, and archaeological excavations do not invariably attest to the evidence of scriptoria.

[16] Scriptoria, in the physical sense of a room set aside for the purpose, perhaps mostly existed in response to specific scribal projects; for example, when a monastic (and) or regal institution wished a large number of texts copied.

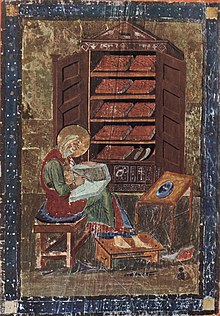

[19] The well-lit niches half a meter deep, provisions for hypocausts beneath the floors to keep the spaces dry, have prototypes in the architecture of Roman libraries.

[20] The monastery built in the second quarter of the 6th century under the supervision of Cassiodorus at the Vivarium near Squillace in southern Italy contained a scriptorium, for the purpose of collecting, copying, and preserving texts.

Cassiodorus also established a library where, at the end of the Roman Empire, he attempted to bring Greek learning to Latin readers and to preserve texts both sacred and secular for future generations.

[22] Cassiodorus' contemporary, Benedict of Nursia, allowed his monks to read the great works of the pagans in the monastery he founded at Monte Cassino in 529.

The creation of a library here initiated the tradition of Benedictine scriptoria, where the copying of texts not only provided materials needed in the routines of the community and served as work for hands and minds otherwise idle, but also produced a marketable end-product.

Saint Jerome stated that the products of the scriptorium could be a source of revenue for the monastic community, but Benedict cautioned, "If there be skilled workmen in the monastery, let them work at their art in all humility".

They fostered copying and literary work that by its excellence and production changed the history of the South Slavic literature and languages spreading its influence all over the Orthodox Balkans.

Although it is not a monastic rule as such, Cassiodorus did write his Institutes as a teaching guide for the monks at Vivarium, the monastery he founded on his family's land in southern Italy.

He cautions over-zealous scribes to check their copies against ancient, trustworthy exemplars and to take care not to change the inspired words of scripture because of grammatical or stylistic concerns.

Montalembert cites one such sixth-century document, the Rule of Saint Ferréol, as prescribing that "He who does not turn up the earth with the plough ought to write the parchment with his fingers.

Another of Montalembert's examples is of a scribal note along these lines: "He who does not know how to write imagines it to be no labour, but although these fingers only hold the pen, the whole body grows weary.

[39] Among the reasons he gives for continuing to copy manuscripts by hand, are the historical precedent of the ancient scribes and the supremacy of transcription to all other manual labor.

In turn, each Psalm studied separately would have to be read slowly and prayerfully, then gone through with the text in one hand (or preferably committed to memory) and the commentary in the other; the process of study would have to continue until virtually everything in the commentary has been absorbed by the student and mnemonically keyed to the individual verses of scripture, so that when the verses are recited again the whole phalanx of Cassiodorian erudition springs up in support of the content of the sacred text".