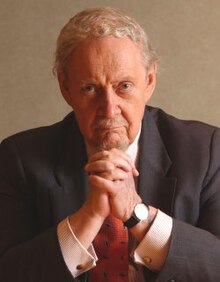

Robert Bork

Robert Heron Bork (March 1, 1927 – December 19, 2012) was an American legal scholar who served as solicitor general of the United States from 1973 until 1977.

During the October 1973 Saturday Night Massacre, Bork became acting U.S. Attorney General after his superiors in the U.S. Justice Department chose to resign rather than fire Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox, who was investigating the Watergate scandal.

His nomination attracted unprecedented media attention and efforts by interest groups to mobilize opposition to his confirmation,[3] primarily due to his outspoken criticism of the Warren and Burger Courts and his role in the Saturday Night Massacre.

As Solicitor General, he argued several high-profile cases before the Supreme Court in the 1970s, including 1974's Milliken v. Bradley, where his brief in support of the State of Michigan was influential among the justices.

Bork hired many young attorneys as assistants who went on to have successful careers, including judges Danny Boggs and Frank H. Easterbrook as well as Robert Reich, later Secretary of Labor in the Clinton administration.

Bork claimed he carried out the order under pressure from Nixon's attorneys and intended to resign immediately afterward, but was persuaded by Richardson and Ruckelshaus to stay on for the good of the Justice Department.

The case involved James L. Dronenburg, a sailor who had been administratively discharged from the United States Navy for engaging in homosexual conduct.

[23] Defunct Newspapers Journals TV channels Websites Other Congressional caucuses Economics Gun rights Identity politics Nativist Religion Watchdog groups Youth/student groups Social media Miscellaneous Other President Reagan nominated Bork for associate justice of the Supreme Court on July 1, 1987, to replace retiring Associate Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. A hotly contested United States Senate debate over Bork's nomination ensued.

Bork is one of four Supreme Court nominees (along with William Rehnquist, Samuel Alito, and Brett Kavanaugh) to have been opposed by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Before Justice Powell's expected retirement on June 27, 1987, some Senate Democrats had asked liberal leaders to "form a 'solid phalanx' of opposition" if President Reagan nominated an "ideological extremist" to replace him, assuming it would tilt the court rightward.

Following Bork's nomination, Senator Ted Kennedy took to the Senate floor with a strong condemnation of him, declaring: Robert Bork's America is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens' doors in midnight raids, schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists could be censored at the whim of the Government, and the doors of the Federal courts would be shut on the fingers of millions of citizens for whom the judiciary is—and is often the only—protector of the individual rights that are the heart of our democracy.

[31] Bork contended in his book, The Tempting of America, that the brief prepared for then-Senator Joe Biden, Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, "so thoroughly misrepresented a plain record that it easily qualifies as world class in the category of scurrility.

The rapid response to Kennedy's "Robert Bork's America" speech stunned the Reagan White House, and the accusations went unanswered for 2+1⁄2 months.

[37] Dolan justified accessing the list on the ground that Bork himself had stated that Americans had only such privacy rights as afforded them by direct legislation.

Two Democratic senators (David Boren of Oklahoma, and Fritz Hollings of South Carolina) voted in favor of his nomination, while six Republican senators (John Chafee of Rhode Island, Bob Packwood of Oregon, Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania, Robert Stafford of Vermont, John Warner of Virginia, and Lowell Weicker of Connecticut) voted against it.

Feminist Florynce Kennedy addressed the conference on the importance of defeating the nomination of Clarence Thomas to the U.S. Supreme Court, saying: "We're going to bork him.

In March 2002, the Oxford English Dictionary added an entry for the verb "bork" as U.S. political slang, with this definition: "To defame or vilify (a person) systematically, esp.

Circuit, and was for several years both a professor at George Mason University School of Law and a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research.

Bork's critique was harder-edged than Bickel's, writing: "We are increasingly governed not by law or elected representatives but by an unelected, unrepresentative, unaccountable committee of lawyers applying no will but their own."

)[51][52] Robert P. George explained Jaffa's critique this way: "He attacks Rehnquist and Scalia and Bork for their embrace of legal positivism that is inconsistent with the doctrine of natural rights that is embedded in the Constitution they are supposed to be interpreting.

During the period these books were written, as well as most of his adult life, Bork was an agnostic, a fact used pejoratively behind the scenes by Southern Democrats when speaking to their evangelical constituents during his Supreme Court nomination process.

[56][57] He came to repudiate his earlier views, saying in his 1987 confirmation hearing that the Civil Rights Act and other racial equality legislation of the 1960s "helped bring the nation together in ways which otherwise would not have occurred.

When asked about his views on unenumerated constitutional rights during his confirmation hearings by Arizona Senator Dennis DeConcini, Bork famously compared the Ninth Amendment to an uninterpretable inkblot, too vague for judges to meaningfully enforce.

[66] In 2003, he published Coercing Virtue: The Worldwide Rule of Judges, an American Enterprise Institute book that includes Bork's philosophical objections to the phenomenon of incorporating international ethical and legal guidelines into the fabric of domestic law.

In particular, he focused on problems he viewed as inherent in the federal judiciaries of Israel, Canada, and the United States—countries where he believes courts have exceeded their discretionary powers, discarded precedent and common law and instead substituted their own liberal judgment.

Bork advocated modifying the Constitution to allow Congressional supermajorities to override Supreme Court decisions, similar to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms' notwithstanding clause.

Although an opponent of gun control,[67] Bork denounced what he called the "NRA view" of the Second Amendment, something he described as the "belief that the constitution guarantees a right to Teflon-coated bullets."

[68][69] He is quoted as saying that the gun lobby's interpretation of the Second Amendment was intentional deception, not "law as integrity," and that states could technically pass a ban on assault weapons.

"[72][73] On June 6, 2007, Bork filed suit in federal court in New York City against the Yale Club over an incident that had occurred a year earlier.

[76] On June 7, 2007, Bork with several others authored an amicus brief on behalf of Scooter Libby arguing that there was a substantial constitutional question regarding the appointment of the prosecutor in the case, reviving the debate that had previously resulted in the Morrison v. Olson decision.