Robert Seymour (illustrator)

After the rejection of his second Royal Academy submission, he continued to paint in oils, mastered techniques of copper engraving, and began illustrating books for a living.

From 1822–27, Seymour produced designs for a wide range of subjects including: poetry; melodramas; children's stories; and topographical and scientific works.

A steady supply of such work enabled him to live comfortably and enjoy his library and fishing and shooting expeditions with his friends: Lacey the publisher, and the illustrator George Cruikshank.

In 1830, having mastered the art of etching, Seymour then lithographed separate prints and book illustrations; he was then invited by McLean to produce the 1830 caricature magazine called Looking Glass, as etched throughout by William Heath, for which Seymour produced four large lithographed sheets of illustrations, usually drawn several to a page, every month for the following six years, until his death in 1836.

In 1831, Seymour began work for a new magazine called Figaro in London (pre-Punch), producing 300 humorous drawings and political caricatures to accompany the mundane, political topics of the day and the texts of owner and editor Gilbert à Beckett (1811–56), and a' Beckett's less successful Comic Magazine.

A cheap weekly, Figaro reflected the clever but abusive character of à Beckett, a friend of Charles Dickens and the publisher of George Cruikshank, who, in 1827, protested at Seymour's parody of his work and nom-de-plume of 'Shortshanks'.

Graham Everitt, in English Caricaturists & Graphic Humourists of the Nineteenth Century, (London, 1885), wrote, "The mainstay and prop of the paper from its commencement was Seymour."

Author Joseph Grego, writing sixty-six years after Seymour's death, repeated a claim that arose in the 1880's that a' Beckett's humiliating public smear was attributed as a cause for the coroner's suicide verdict.

[1] Seymour's eminence as an illustrator now equalled that of his friend George Cruikshank and, as one of the greatest artists since the days of Hogarth, Sir Richard Phillips, predicted that, if he lived, he would become President of the Royal Academy.

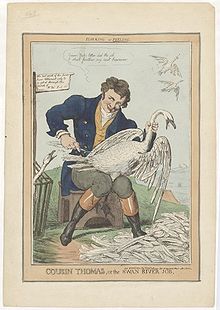

He primarily poked fun at politicians and sportsmen, although he sometimes predicted the future with his tongue firmly in his cheek, and took on social issues such as excessive drinking.

Due to the lack of time, Seymour agreed to this change and approved Dickens' appointment as his writer for the series.

Seymour already had the main characters in sketch form, and had already engraved the first four Pickwick illustrations onto steel plates in 1835 ready for publication.

For the second instalment, Dickens began to cause problems, claimng his honeymoon following his marriage to Catherine Hogarth would prevent him from writing a fully original text for the instalment and insisting he be allowed to insert an existing story of his, 'The Stroller's Tale,' and also insisting that Seymour draw an illustration based on that story.

Extensive research over a number of years in the early 2000's by Dickens scholar Stephen Jarvis, author of Death and Mr Pickwick, found no trace in official records of any adult John Foster of Richmond during the relevant period.

It is possible that Seymour had mentioned to Chapman and Hall that he wanted his Pickwick Club story to follow the same lines as a popular 1834 novel about bumbling country squire John Mytton, but with a sporting bias.

That Mytton book, The Chase, the Turf and the Road, was by Charles James Apperly, who wrote it using the pen name of Nimrod.

The frontage illustration that was issued on the 'wrapper' or cover of the first magazine edition reads "The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club – containing a faithful record of the perambulations, perils, travels, adventures and Sporting Transactions of the corresponding members.

Chapman and Hall placed advertisements for The Postumus Papers of the Pickwick Club in The Times and The Athenaeum in which the use of four illustrations by Seymour was strongly promoted.

Following his death, Seymour's name was removed by the publishers from subsequent reprints of the first instalment, produced to meet demand once The Pickwick Papers gained in popularity.

He was found early that morning by his kitchen maid lying in the garden behind his summer house, killed by a gunshot wound to the chest.

Buss may have taken this from an erroneous report in the weekly sporting newspaper Bell's Life in London that appeared some days after Seymour's death.

[2] Three days earlier, Seymour had called at Dickens's lodgings at Furnival's Inn, Holborn, and they had discussed the artwork for the chapter on the dying clown story.

Dickens's and Edward Chapman's statements of the incident, (albeit without explanation of how they knew) state that Seymour worked on the new plates well into that night and was found shot the next day.

At the inquest, the post mortem report presented to the coroner showed that the shotgun blast had shattered Seymour's heart.

Those publishers included William Kidd, who was waiting for Seymour to commence the second edition of the successful 1835-1836 Odd Volume with his friend George Cruikshank, who wrote that he had allowed Seymour to take the lead on the project due to his 'far superior talent' (see Cruikshank's quote below from the preface of the first Odd Volume).

No other testimony suggesting a troubled mental state past or present was produced at the inquest, which also heard that Seymour was comfortably off and had no money worries.

[1] Journalist Shelton Mackenzie was clearly unaware of this evidence presented to the coroner in 1836, because in his 1870 biography of Charles Dickens, published in Philadelphia, Mackenzie claimed that Seymour had been in poor health at the time of his death as a result of poverty, poor habits and a supposed inability to resist the temptation of drink.

In a continuation of Mackenzie's slurs, it would be claimed in the late nineteenth century that Seymour had a 'dark' personality and his death came after a struggle with mental illness and a breakdown in 1830.

The tombstone has since been acquired by the Charles Dickens Museum at 48 Doughty Street, London where it went on permanent public display from 27 July 2010.

This is plausibly based on inconsistencies in Dickens's various prefaces to the book and flaws in Chapman's supporting testimony, as well as a scrupulous examination of other evidential sources, including internal evidence from Seymour's own work on the project.