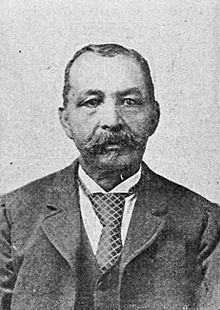

Robert Smalls

After the Civil War, Smalls returned to Beaufort and became a politician, winning election as a Republican to the South Carolina Legislature and the United States House of Representatives during the Reconstruction era.

Robert Smalls was born on April 5, 1839, in Beaufort, South Carolina, to Lydia Polite, a woman enslaved by Henry McKee.

[8] Smalls appeared content and had the confidence of the Planter's crew and owners, but, at some time in April 1862, he began to plan an escape.

[2] On May 12, 1862, the Planter traveled ten miles southwest of Charleston to stop at Coles Island, a Confederate post on the Stono River that was being dismantled.

They cried and screamed when they learned what they had stumbled into, and the men struggled to quiet them.... Later, once the shock had worn off, those women admitted that they were glad for a chance at freedom....[11]: 19 [12]At some point, three crew members pretended to escort the family members[b] back home, but they circled around and hid aboard another steamer[c] docked at the North Atlantic wharf.

Smalls guided the ship past the five Confederate harbor forts without incident, as he gave the correct steam-whistle signals at checkpoints.

One of the men aboard later said, “When we drew near the fort every man but Robert Smalls felt his knees giving way and the women began crying and praying again.

[11]: 24–25 [12]: 39 The alarm was only raised after the ship was beyond gun range, for, rather than turn east towards Morris Island, Smalls had headed straight for the Union Navy fleet, replacing the rebel flags with a white bed sheet that had been brought by his wife.

As the steamer came near, and under the stern of the Onward, one of the Colored men stepped forward, and taking off his hat, shouted, "Good morning, sir!

][3]The Onward's captain, John Frederick Nickels,[16] boarded the Planter, and Smalls asked for a United States flag to display.

In addition to its own light guns, Planter carried the four loose artillery pieces from Coles Island and 200 pounds of ammunition.

Parrott again forwarded the Planter to flag officer Samuel Francis Du Pont at Port Royal, describing Smalls as very intelligent.

Federal officers were surprised to learn from Smalls that contrary to their calculations, only a few thousand troops remained to protect the area, the rest having been sent to Tennessee and Virginia.

[6] This intelligence allowed Union forces to capture Coles Island and its string of batteries without a fight on May 20, a week after Smalls's escape.

[2] Du Pont was impressed, and wrote the following to the Navy secretary in Washington: "Robert, the intelligent slave and pilot of the boat, who performed this bold feat so skillfully, informed me of [the capture of the Sumter gun], presuming it would be a matter of interest."

However, with the encouragement of Major General David Hunter, the Union commander at Port Royal, Smalls went to Washington, D.C., in August 1862 with Rev.

[16] On December 1, 1863, Smalls was piloting the Planter under Captain James Nickerson on Folly Island Creek when Confederate batteries at Secessionville opened fire.

[2] In December 1864, Smalls and the Planter moved to support William T. Sherman's army in Savannah, Georgia at the destination point of his March to the Sea.

[20] He continued to pilot the Planter, serving a humanitarian mission of taking food and supplies to freedmen who had lost their homes and livelihoods during the war.

Many sources also state that General Gillmore promoted Smalls to captain in December 1863 after he saved the Planter when it was under attack near Secessionville.

In 1883, a bill passed committee to put him on the Navy retired list, but in the end it was halted, allegedly due to Smalls being African-American.

[2] In 1883, during discussion of the bill to put Smalls on the Navy retired list, a report stated that the 1862 appraisal of the Planter was "absurdly low" and that a fair valuation would have been over $60,000.

[20] That April, the Radical Republicans who controlled Congress overrode President Andrew Johnson's vetoes and passed a Civil Rights Act.

In 1870, in anticipation of a Reconstruction-based prosperity, Smalls, with fellow representatives Joseph Rainey, Alonzo Ransier and others, formed the Enterprise Railroad, an 18-mile horse-drawn railway line that carried cargo and passengers between the Charleston wharves and inland depots.

[20] Smalls was a Republican, the political party that dominated the Northern states and passed laws granting protections for African Americans in the aftermath of the Civil War.

As part of wide-ranging Democratic Party efforts to reduce African-American political power, Smalls was charged and convicted of taking a bribe five years earlier in connection with the awarding of a printing contract.

[20] In 1890, he was appointed by President Benjamin Harrison as collector of the Port of Beaufort, a position that he held until 1913 except during Democrat Grover Cleveland's second term.

For many decades, this state constitution survived legal challenges, resulting in both the exclusion of African Americans from political participation and the crippling of the Republican Party throughout South Carolina.

In 1913, in one of his final actions as community leader, he played an important role in stopping a lynch mob from killing two black suspects in the murder of a white man.

The monument to Smalls in this churchyard is inscribed with his 1895 statement to the South Carolina legislature: "My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere.