Robert Stephenson

[11] As an apprentice Stephenson worked hard and lived frugally, and unable to afford to buy a mining compass, he made one that he would later use to survey the High Level Bridge in Newcastle.

[16] Ways were investigated in the early 19th century to transport coal from the mines in the Bishop Auckland area to Darlington and the quay at Stockton-on-Tees, and canals had been proposed.

The Welsh engineer George Overton suggested a tramway, surveyed a route in September 1818 and the scheme was promoted by Edward Pease at a meeting in November.

[24][25] By the end of 1821 they reported that a usable line could be built within the bounds of the act of Parliament, but another route would be shorter and avoid deep cuttings and tunnels.

George could have afforded to send his son to a full degree course at Cambridge but agreed to a short academic year as he wished that Robert should not become a gentleman but should work for his living.

Robert first helped William James to survey the route of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway and then attended classes at Edinburgh University between October 1822 and April 1823.

To prepare for the trip, Stephenson took Spanish lessons, visited mines in Cornwall, and consulted a doctor, who advised that such a change of climate would be beneficial to his health.

[44] Travelling onward, Robert found the heavier equipment at Honda on the Magdalena River; there was no way to get it to the mines as the only route was a narrow and steep path.

While waiting for a ship to New York, he met the railway pioneer Richard Trevithick,[note 5] who had been looking for South American gold and silver in the mines of Peru and Costa Rica, and gave him £50 so he could buy passage home.

The Lancashire Witch was built with inclined cylinders that allowed the axles to be sprung, but the L&MR withdrew the order in April; by mutual agreement the locomotive was sold to the Bolton and Leigh Railway.

[61][note 8] The performance-enhancing idea to heat water using many small diameter tubes through the boiler was communicated to Robert via a letter from his father who heard about it from Henry Booth and Marc Seguin .

[63][note 9] With both George and Booth in Liverpool, Robert was responsible for the detail design, and he fitted twenty-five 3-inch (76 mm) diameter tubes from a separate firebox through the boiler.

Hackworth was building Globe at the Robert Stephenson & Co. works at the same time, and Edward Bury delivered Liverpool the same month, both with cylinders under the boiler.

[83] Robert stood as the engineering authority when a bill was presented to Parliament in 1832,[84] and it was suggested during cross-examination that he had allowed too steep an angle on the side of the cutting at Tring.

A drawing office with 20–30 draughtsmen was established at the empty Eyre Arms Hotel in St John's Wood; George Parker Bidder, whom Robert had first met at Edinburgh University, started working for him there.

[94] The line permitted by the 1833 act of Parliament terminated north of Regent's Canal at Camden (near Chalk Farm Underground station), as Baron Southampton, who owned the land to the south, had strongly opposed the railway in the House of Lords in 1832.

[104] The Stanhope and Tyne Railroad Company (S&TR) had been formed in 1832 as a partnership to build a railway between the lime kilns at Lanehead Farmhouse and the coal mines at Consett in County Durham.

[112][113] Some work still needed to be completed on the L&BR, and the North Midland Railway and lines from Ostend to Liège and Antwerp to Mons in Belgium required Robert's attention.

He moved to Cambridge Square in Westminster to be nearer to London's gentlemen's clubs, but soon afterwards the house was damaged by fire and he lived in temporary accommodation for ten months.

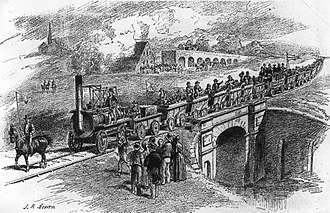

A special train left Euston at 5:03 am, and travelling via Rugby, Leicester, Derby, Chesterfield and Normanton, reached Gateshead, south of the River Tyne, at 2:24 pm.

Festivities were held in the Newcastle Assembly Rooms, where George was introduced as the man who had "constructed the first locomotive that ever went by its own spontaneous movement along iron rails", although there were people present who should have known better.

[122][123][124] When George had built the Stockton & Darlington and Liverpool & Manchester he had placed the rails 4 ft 8 in (1,422 mm) apart, as this was the gauge of the railway at the Killingworth Colliery.

[note 16] Isambard Kingdom Brunel, chief engineer to the Great Western Railway, had adopted the 7 ft (2,134 mm) or broad gauge, arguing that this would allow for higher speeds.

Conder attended the inquest at Chester: he recounts that Paisley was so agitated he was nearly unable to speak; Robert was pale and haggard and the foreman of the jury seemed determined to get a verdict of manslaughter.

The first train crossed the Tyne on a temporary wooden structure in August 1848; the iron bridge was formally opened by Queen Victoria in September 1849, Robert having been elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in June.

[147] In 1850, the pope appointed Bishop Wiseman as the first English Roman Catholic Cardinal since the Reformation; Robert wrote in a private letter that this was aggressive, saying that in the "battle as to the mere form in which the creator is to be worshiped – the true spirit of Christianity is never allowed to appear.

[155][156][157] Robert found that he attracted the unwelcome attention of inventors and promoters; if he was too ill to be at Great George Street they visited him at home in Gloucester Square.

He was ill that summer, but sailed to Oslo in the company of George Parker Bidder to celebrate the opening of the Norwegian Trunk railway and to receive the Knight Grand Cross of the order of St. Olaf.

He fell ill at the banquet on 3 September and returned to England on board Titania in the company of a doctor, but the journey took seven days after the yacht ran into a storm.

Two thousand tickets were issued, but 3000 men[note 22] were admitted to the service at Westminster Abbey, where he was buried beside the great civil engineer Thomas Telford.