Roberto Silva Renard

He is mostly remembered as the military chief that carried out the Santa María of Iquique School massacre in 1907, where 2,000-3,500 striking saltpeter miners, along with their wives and children, were killed.

This was the start of the 18 Pence Strike (Spanish: La huelga de los 18 peniques), the name referring to the size of the wage being demanded by the nitrate miners.

On December 16, thousands of striking workers arrived at the provincial capital, the port city of Iquique, in support of the nitrate miners' demands and with the aim of prodding the authorities to act.

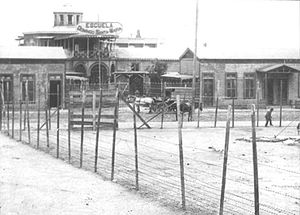

Soon after the journeys to Iquique began, this great conglomeration of workers met at the Manuel Montt plaza and at the Santa María School, asking the government to mediate between them and the bosses of the foreign (English) nitrate firms to resolve their demands.

The arrival at the port December 19 of the titular intendant, Carlos Eastman Quiroga, of General Silva Renard, chief of the First Military Zone of the Chilean Army, and of Colonel Sinforoso Ledesma was cheered by the workers because a nitrate miners' petition to the government nearly two years earlier, under the previous president, had received an encouraging response, although the demands had not been satisfied.

The ministry relayed orders to the strikers to leave the plaza and the school and gather at the horse racing track, where they were to board trains and return to work.

While the meeting with Intendant Eastman was taking place in the "Buenaventura nitrate works", a group of workers and their families tried to leave the spot, but troops opened fire on them by the railroad tracks and kept shooting.

At 2:30 in the afternoon, General Silva Renard told the leaders of the workers' committee that if the strikers did not start heading back to work within one hour, the troops would open fire on them.

At the hour indicated by Silva Renard, he ordered the soldiers to shoot the workers' leaders, who were on the school's roof, and they fell dead with the first volley.

[3] Elías Lafertte, who witnessed the events, tells: Between 3.30 and four in the afternoon, there was a terrible expectation inside the Santa María school.

At that time, colonel Roberto Silva Renard arrived, mounted like Napoleón in a white horse, to this unequal battle.

The noise of the shots was deafening (…)[3]The multitude, desperate and trying to escape, surged toward the soldiers, and were fired upon with rifles and machine guns.

The survivors of the massacre were brought at saber point to the Club Hípico, whence they were sent back to work, where they were subjected to a reign of terror.

Once in custody, Ramón vehemently denied other parties' involvement in the assassination, while the worker's organizations held public campaigns to raise money for his defense.

[5] Renard survived the attack, but suffered permanent effects from the injuries: he lost all movement on half of his face, became blind, and was mostly an invalid until his death in 1920.