Film Booking Offices of America

Two months later, Kennedy and RCA executive David Sarnoff arranged the merger between FBO and the Keith-Albee-Orpheum theater circuit that created RKO, one of the major studios of Hollywood's Golden Age.

[3] The company handled American-made trucks, cars, automobile accessories, and Bell & Howell motion picture equipment; its initial film distribution focus was on the Northern European, South Asian, and Latin American markets.

[8] To accompany its features, Robertson-Cole also acquired a wide variety of serials and other shorts, from Supreme Comedies with Harry Depp and Teddy Sampson to a biweekly series, On the Borderland of Civilization, filmed by adventurer Martin Johnson.

[13] With its move into production, Robertson-Cole needed its own filmmaking studio: in June, it acquired a lot around fifteen acres (six hectares) in size in Los Angeles's fortuitously named Colegrove district, then adjacent to but soon to be subsumed by Hollywood.

[20] At the same time, the business was $5 million in debt from the L.A. studio purchase and draining money—banks were reluctant to issue lines of credit to any but the biggest film companies, and R-C was forced to pay interest rates as high as 18 percent to so-called bonus sharks to access working capital.

The company's primary investor, the Graham's of London firm, turned to Kennedy to find a buyer, giving him a seat on the R-C board, paying him a monthly adviser's fee, and promising a sizable commission.

FBO's top five attractions were led by A Girl of the Limberlost, an adaptation of a novel by bestselling author Gene Stratton-Porter, who had died the previous December; this was followed by Broken Laws, an issue-driven melodrama detailing the dire consequences of not spanking naughty children, and three Fred Thomson "oaters": The Bandit's Baby, The Wild Bull's Lair, and Thundering Hoofs.

[44] From the studio's New York City headquarters, Kennedy swiftly addressed its perennial cash-flow problems, setting up a new business, the Cinema Credits Corporation, to provide FBO with reliable financing at favorable terms.

[46] The president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association, Will Hays—the industry's future censor in chief—was delighted by the new face on the scene; in his eyes, Kennedy signified both a desirable image for the film trade and Wall Street's faith in its prospects.

[63] The studio put out fifty-one features in total that year; for the twelve-month period ending November 15, theater owners judged FBO's top three films to all be Gene Stratton-Porter adaptations, with two Thomson oaters following.

[65] At the same time, Kennedy had aligned with investment banker Elisha Walker and his firm Blair & Co., which had acquired the small Pathé Exchange studio and a stake in Keith-Albee-Orpheum (KAO), a vaudeville exhibition chain owning approximately one hundred theaters across the United States and affiliated with many more; KAO and Blair & Co. together controlled yet another small studio, Producers Distributing Corporation (PDC), famed director Cecil B. DeMille's outlet and one-time fiefdom, which was now in effect a Pathé subsidiary.

In March, nominally acting as an unpaid "special advisor" to Pathé (he would eventually receive 100,000 shares of stock and thousands of dollars in retroactive salary), Kennedy took effective charge of PDC operations, beginning the process of edging DeMille out.

[71] To date, FBO's experiments with sound had all been funded by RCA; on August 22, as Kennedy was crossing the Atlantic for a European vacation, Variety announced that he had finally signed a formal licensing agreement to pay for his studio's use of Photophone recording.

[77] In its final year of operation, of FBO's top five box office films according to theater owners, three were again Gene Stratton-Porter adaptations, including The Keeper of the Bees, first released in October 1925 and making its fourth appearance in the annual balloting; the others were the Austrian import Moon of Israel and The Great Mail Robbery.

Due to its zeal for cost cutting, FBO was reputed to be especially meticulous in the execution of a practice then common among distributors: rounding up its release prints at the end of a picture's run and melting them down to recover the silver in the film emulsion.

[86] According to the Library of Congress's American Silent Feature Film Database, to the tiny remaining corpus of Thomson's work for FBO may now be added complete prints of The Dangerous Coward (1924) and A Regular Scout (1926) at the George Eastman House.

[90] Pauline Frederick, celebrated for her performance in the September 1920 Goldwyn Pictures tear-jerker Madame X, immediately cashed in with a top-tier contract from Robertson-Cole, for whom she starred in more than half a dozen melodramas, beginning with A Slave of Vanity just two months later.

[94] Brent made a specialty of melodramatic pictures with a crime angle, often billed as "crook melodramas"—in Midnight Molly (1925), she played an ambitious politician's faithless wife and her look-alike, a high-end cat burglar.

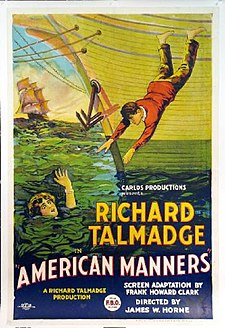

[99] In October, Talmadge was judged to have been FBO's biggest non-Western draw of the year; in the first annual Exhibitors Herald theater owners' poll of top box office names, he placed thirtieth out of sixty.

[101] Signing a new contract in 1925, the former Yale halfback demonstrated his range by playing a "fast riding motorcycle copper" in a May release, a "battling policeman" in September, and Breckenrdige Gamble, a bored millionaire turned international secret agent, in October.

"[113] When the biggest movie star in the world, Rudolph Valentino, split from his wife, Natacha Rambova, she was swiftly enlisted by the studio to costar with Clive Brook in the sensitively titled When Love Grows Cold (1926).

[114] Under Kennedy's control, the studio focused on marketing its roster of films as suitable for the "average American" and the entire family: "We can't make pictures and label them 'For Children,' or 'For Women' or 'For Stout People' or 'For Thin Ones.'

"[115] Though Kennedy ended the scandal-sheet specials, FBO still found occasion for celebrity casting: One Minute to Play (1926), directed by Sam Wood, marked the film debut of football great "Red" Grange.

[119] When one of Thomson's "oaters", The Two-Gun Man (1926), made it to New York's Warners' Theatre, the growing studio's Times Square showcase, it demonstrated that a Western, even one without Mix, could draw audiences to a first-run house in the most cosmopolitan of markets.

"[125] Tyler's appeal was also enhanced by his human costars—Frankie Darro (tied for fifty-fourth in the poll) as his young sidekick on over two dozen occasions and starlets such as Doris Hill, Nora Lane, Sharon Lynn, and in Born to Battle (1926), a twenty-five-year-old Jean Arthur.

[160] In-house, Frances Marion, who would win two writing Oscars in the 1930s, created the stories for seven of the FBO pictures starring her husband, Fred Thomson—for these brawny cowboy tales, such as Ridin' the Wind (1925) and The Tough Guy (1926), she used the pseudonym Frank M. Clifton (the "patronymic" was Thomson's middle name).

[163] Both George O'Hara's and Alberta Vaughn's initial short series for FBO—each directed by Malcolm St. Clair—were hits, so in the second half of 1924 the studio made a bid at teaming them in the twelve-part The Go-Getters, spoofing popular films and classic stories with chapters such A Kick for Cinderella.

[166] Of particular historical interest are two independently produced series of slapstick comedies released by the studio: Between 1924 and 1927, Joe Rock provided FBO with a substantial annual slate of two-reelers (twenty-six per year as of their last contract); twelve of those from 1924–25 starred Stan Laurel, before his famous partnership with Oliver Hardy.

[167] West of Hot Dog (1924), according to historian Simon Louvish, contains "one of [Laurel]'s finest gags," involving a level of cinematic technique that bears comparison to Buster Keaton's classic Sherlock Jr.[168] In 1926–27, the company released more than a dozen shorts by innovative comedian/animator Charles Bowers, whose work imaginatively mixed live action and three-dimensional model animation.

[170] In 1925–26, the studio put out twenty-six cartoons by animator William Nolan based on George Herriman's now famed Krazy Kat newspaper comic strip, licensed by the wife-husband distribution team of Margaret Winkler and Charles Mintz.