Walt Disney

New animated and live-action films followed after World War II, including the critically successful Cinderella (1950), Sleeping Beauty (1959) and Mary Poppins (1964), the last of which received five Academy Awards.

[14] There, Disney attended the Benton Grammar School, where he met fellow-student Walter Pfeiffer, who came from a family of theatre fans and introduced him to the world of vaudeville and motion pictures.

Although New York was the center of the cartoon industry, he was attracted to Los Angeles because his brother Roy was convalescing from tuberculosis there,[37] and he hoped to become a live-action film director.

"[56] Mickey Mouse first appeared in May 1928 as a single test screening of the short Plane Crazy, but it, and the second feature, The Gallopin' Gaucho, failed to find a distributor.

[62] With the loss of Powers as distributor, Disney studios signed a contract with Columbia Pictures to distribute the Mickey Mouse cartoons, which became increasingly popular, including internationally.

[83][k] The success of Snow White heralded one of the most productive eras for the studio; the Walt Disney Family Museum calls the following years "the 'Golden Age of Animation'".

[87] While a federal mediator from the National Labor Relations Board negotiated with the two sides, Disney accepted an offer from the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs to make a goodwill trip to South America, ensuring he was absent during a resolution he knew would be unfavorable to the studio.

[91] The strike temporarily interrupted the studio's next production, Dumbo (1941), which Disney produced in a simple and inexpensive manner; the film received a positive reaction from audiences and critics alike.

[94] Disney also produced several propaganda productions, including shorts such as Der Fuehrer's Face—which won an Academy Award—and the 1943 feature film Victory Through Air Power.

[114] Although there were early minor problems with the park, it was a success, and after a month's operation, Disneyland was receiving over 20,000 visitors a day; by the end of its first year, it attracted 3.6 million guests.

[118] ABC was pleased with the ratings, leading to Disney's first daily television program, The Mickey Mouse Club, a variety show catering specifically to children.

He was consultant to the 1959 American National Exhibition in Moscow; Disney Studios' contribution was America the Beautiful, a 19-minute film in the 360-degree Circarama theater that was one of the most popular attractions.

In 1963, he presented a project to create a theme park in downtown St. Louis, Missouri; he initially reached an agreement with the Civic Center Redevelopment Corp, which controlled the land, but the deal later collapsed over funding.

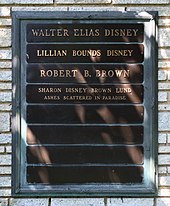

[161] The marriage was generally happy, according to Lillian, although according to Disney's biographer Neal Gabler she did not "accept Walt's decisions meekly or his status unquestionably, and she admitted that he was always telling people 'how henpecked he is'.

"[162][w] Lillian had little interest in films or the Hollywood social scene and she was, in the words of the historian Steven Watts, "content with household management and providing support for her husband".

[175] However, while Walt Disney was made a "Special Agent in Charge Contact" in 1954, FBI officials claim this was largely an honorary title regularly awarded to members of a community who might be of use to the bureau.

[176][177] The FBI declassified and released Walt Disney's file on their website, and revealed that much of Disney's correspondence with the bureau (via studio personnel) was in relation to the production of educational films; such as a certain installment of the "Career Day" newsreel segments on The Mickey Mouse Club focusing on the bureau (which aired in January 1958), as well as an unmade 1961 educational short warning children about the dangers of child molestation.

[186] Mark Langer, in the American Dictionary of National Biography, writes that "Earlier evaluations of Disney hailed him as a patriot, folk artist, and popularizer of culture.

"[58] Steven Watts wrote that some denounce Disney "as a cynical manipulator of cultural and commercial formulas",[186] while PBS records that critics have censured his work because of its "smooth façade of sentimentality and stubborn optimism, its feel-good re-write of American history".

[196] Disney also demonstrated his political naivete in an October 1933 article for Overland Monthly claiming: "Of course there must be millions of people who have a downright feeling of animosity for our M. Mouse.

As early as October 1940 (over a year before America's entry into the war), Disney began enlisting contracts from various branches of the United States Armed Forces to make training films,[199] and in March 1941 he held a luncheon with Government representatives formally offering his services "...for national defence industries at cost and without profit.

They nourished a genial cultural imperialism that magically overran the rest of the globe with the values, expectations, and goods of a prosperous middle-class United States.

"[212] Film historian Jay P. Telotte acknowledges that many see Disney's studio as an "agent of manipulation and repression", although he observes that it has "labored throughout its history to link its name with notions of fun, family, and fantasy".

[213] John Tomlinson, in his study Cultural Imperialism, examines the work of Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart, whose 1971 book Para leer al Pato Donald (transl.

How to Read Donald Duck) identifies that there are "imperialist ... values 'concealed' behind the innocent, wholesome façade of the world of Walt Disney"; this, they argue, is a powerful tool as "it presents itself as harmless fun for consumption by children.

"[214] Tomlinson views their argument as flawed, as "they simply assume that reading American comics, seeing adverts, watching pictures of the affluent ... ['Yankee'] lifestyle has a direct pedagogic effect".

[218] In 2001, the German author Peter Stephan Jungk published Der König von Amerika (trans: The King of America), a fictional work of Disney's later years that re-imagines him as a power-hungry racist.

[222] Journalist Bosley Crowther argues that Disney's "achievement as a creator of entertainment for an almost unlimited public and as a highly ingenious merchandiser of his wares can rightly be compared to the most successful industrialists in history.

Through technological innovations and alliances with governments and corporations, he transformed a minor studio in a marginal form of communication into a multinational leisure industry giant.

Despite his critics, his vision of a modern, corporate utopia as an extension of traditional American values has possibly gained greater currency in the years after his death.