Terrestrial planet

All terrestrial planets in the Solar System have the same basic structure, such as a central metallic core (mostly iron) with a surrounding silicate mantle.

[4] Another rocky asteroid 2 Pallas is about the same size as Vesta, but is significantly less dense; it appears to have never differentiated a core and a mantle.

Another Jovian moon Europa has a similar density but has a significant ice layer on the surface: for this reason, it is sometimes considered an icy planet instead.

Terrestrial planets can have surface structures such as canyons, craters, mountains, volcanoes, and others, depending on the presence at any time of an erosive liquid or tectonic activity or both.

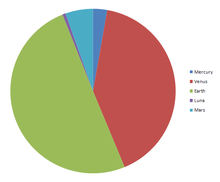

[5] The Solar System has four terrestrial planets under the dynamical definition: Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars.

Some other protoplanets began to accrete and differentiate but suffered catastrophic collisions that left only a metallic or rocky core, like 16 Psyche[4] or 8 Flora respectively.

These include the dwarf planets, such as Ceres, Pluto and Eris, which are found today only in the regions beyond the formation snow line where water ice was stable under direct sunlight in the early Solar System.

It also includes the other round moons, which are ice-rock (e.g. Ganymede, Callisto, Titan, and Triton) or even almost pure (at least 99%) ice (Tethys and Iapetus).

Some of these bodies are known to have subsurface hydrospheres (Ganymede, Callisto, Enceladus, and Titan), like Europa, and it is also possible for some others (e.g. Ceres, Mimas, Dione, Miranda, Ariel, Triton, and Pluto).

The data in the tables below are mostly taken from a list of gravitationally rounded objects of the Solar System and planetary-mass moon.

The first confirmed terrestrial exoplanet, Kepler-10b, was found in 2011 by the Kepler space telescope, specifically designed to discover Earth-size planets around other stars using the transit method.

[20] In the same year, the Kepler space telescope mission team released a list of 1235 extrasolar planet candidates, including six that are "Earth-size" or "super-Earth-size" (i.e. they have a radius less than twice that of the Earth)[21] and in the habitable zone of their star.

In 2016, statistical modeling of the relationship between a planet's mass and radius using a broken power law appeared to suggest that the transition point between rocky, terrestrial worlds and mini-Neptunes without a defined surface was in fact very close to Earth and Venus's, suggesting that rocky worlds much larger than our own are in fact quite rare.

[24] In September 2020, astronomers using microlensing techniques reported the detection, for the first time, of an Earth-mass rogue planet (named OGLE-2016-BLG-1928) unbounded by any star, and free-floating in the Milky Way galaxy.

In 2013, astronomers reported, based on Kepler space mission data, that there could be as many as 40 billion Earth- and super-Earth-sized planets orbiting in the habitable zones of Sun-like stars and red dwarfs within the Milky Way.